The view was the overall appearance of the landscape surrounding a house or a garden. It was one of the most important considerations when chosing a site for a dwelling in the 18th century, as we learned in the earlier posting Location, Location, Location...

We have seen in earlier postings that the words command and view were often used together, see Location--Commanding Views and Prospects. Here are a few more references to the term view as it visually connects the overall relationship between a dwelling or garden with the topography around it.

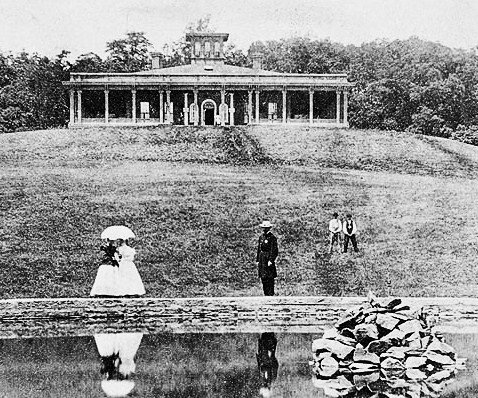

The Garden Facade of Mount Clare near Baltimore, Maryland. It faces downhill toward the Patapsco River which emptys into Baltimore Harbor.

The Garden Facade of Mount Clare near Baltimore, Maryland. It faces downhill toward the Patapsco River which emptys into Baltimore Harbor.Virginian Mary Ambler visited Mount Clare, the home of Charles Carroll and Margaret Tilghman Carroll in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1770, writing, The House where this Gentn & his Lady reside in the Sumer stands upon a very High Hill & has a fine view of Petapsico River You step out of the Door into the Bowlg Green from which the Garden Falls & when You stand on the Top of it there is such a Uniformity of Each side as the whole Plantn seems to be laid out like a Garden.

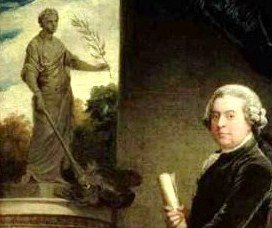

Margaret Tilghman Carroll at the Garden Facade of Mount Clare by Charles Willson Peale.

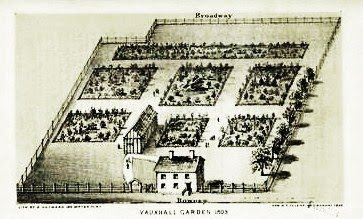

Margaret Tilghman Carroll at the Garden Facade of Mount Clare by Charles Willson Peale.In 1771, the public commercial grounds called Vauxhall Gardens in New York City was mentioned in the New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, The Commodious house and large gardens...known by the name of VAUXHALL...having a very extensive view both up and down the North River.

New York City's Vauxhall Gardens.

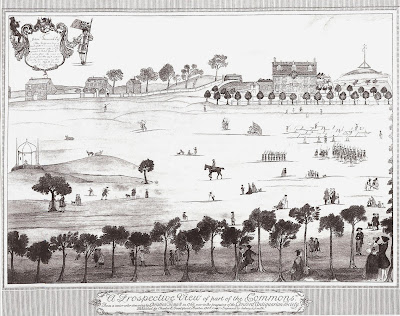

New York City's Vauxhall Gardens.English officer Lt. John Enys visited Boston, Massachusettes, in 1787, noting that, After Dinner we took a walk on the Mall...From hence we went to Beacon Hill from whence we had a Charming View of the town and harbour...there are a number of houses situated on Beacon hill which stand high...That of Governor Hancock stands the most conspicuous just at the top of the common with a full view of the Mall before it besides its distant views of the harbour and adjacent country.

1768 Sidney L. Smith after Christian Remick A Prospective View of Part of the Commons 1902 after a drawing from 1768 Engraving Concord Museum MA

1768 Sidney L. Smith after Christian Remick A Prospective View of Part of the Commons 1902 after a drawing from 1768 Engraving Concord Museum MAIn 1787, a visitor to New Bern, North Carolina, reported that the Governor's "palace is situated with one front to the River Trent and near the Bank, and commands a pleasing view of the Water."

When he visited in January, 1788, Governor John Eager Howard's Belvedere at Baltimore, Maryland, The Seat of Colol. Howard which ...has a charming view of the Water fall at a Mill, a long Rapid below it, a full View of the town of Baltimore and the Point with the shipping in the harbour, the Bason and all the Small craft.

1796 George Beck Detail of The View of Baltimore from Governor John Eager Howard's Garden Park. Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore.

1796 George Beck Detail of The View of Baltimore from Governor John Eager Howard's Garden Park. Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore.Englishman Thomas Twining visited Governor John Eager Howard's Belvedere in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1788, I walked this morning to breakfast with Colonel Howard at Belvidere... Situated upon the verge of the descent upon which Baltimore stands, its grounds formed a beautiful slant towards the Chesapeake...The spot, thus indebted to nature and judiciously embellished, was as enchanting with in its own proper limits as in the fine view which extended far beyond them. The foreground presented luxurious shrubberies and sloping lawns: the distance, the line of the Patapsco and the country bordering on Chesapeak Bay. Both the perfections of the landscape, its near and distant scenery, were united in the view from the bow-window of the noble room in which breakfast was prepared, with the desire, I believe, of gratifying me with this exquisite prospect.

Six years later, visitors were still impressed with the view from Governor Howard's property in Baltimore, Maryland. Moreau de St. Mery wrote of Governor John Eager Howard's Belvedere in 1794, Its elevated situation; its grove of trees; the view from it, which brings back memories of European scenes; all these things together fill every true Frencman with pleasure and regret.

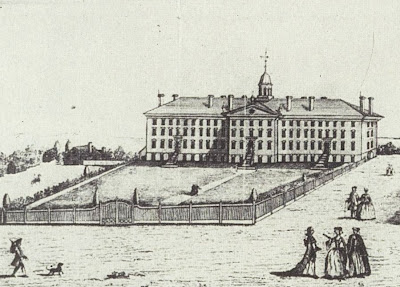

In 1789, Geographer Jedidiah Morse wrote of Nassau Hall at Princeton, New Jersey, The view from the college balcony is extensive and charming.

Detail of Nassau Hall at Princeton, New Jersey in 1764.

Detail of Nassau Hall at Princeton, New Jersey in 1764.Abigail Adams, the wife of John Adams, wrote in 1790, of Bush Hill in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, A variety of fine fields of wheat and grass are in front of the house, and, on the right hand, a pretty view of the Schuylkill presents itself.

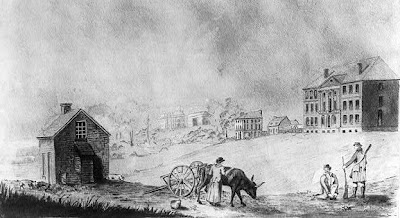

William Hamilton's Bush Hill in Philadelphia

William Hamilton's Bush Hill in PhiladelphiaAround 1734, the Penn family gave attorney Andrew Hamilton land in payment for legal services. In 1740, he built Bush Hill on the property. Vice President John Adams and his wife lived in the house in 1790 & 1791. During Philadelphia's yellow fever epidemic of 1793, a quarantine hospital was set up in the mansion.

Fairmount Park, Philadelphia. August Köllner, Bush Hill and Cholera Hospital.

Fairmount Park, Philadelphia. August Köllner, Bush Hill and Cholera Hospital.When Moreau de St. Mery visited the New York in the 1790s, he wrote, In America almost everything is sacrificed to the outside view...The elevated situation of these country residences, in addition to being healthy, gives them the advantage of a charming view which includes New York and the nearby islands, principally Governor's Island, and is constantly enlivened by the passing of the boats which ply on both rivers.

In 1793, Rev. John Spooner described David Meade's Maycox in Prince George's County, Virginia, These grounds contain about twelve acres, laid out on the banks of the James river...which open as many pleasing views of the river. Rev. John Jones Spooner's papers are at the College of William & Mary Swem Library showing his election to the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, and his installation as minister to Martins Brandon Parish, Prince George County, Virginia.

David Meade's terraced gardens sat directly across the river from the terraced gardens of Westover, almost a mirror image of two landscapes divided by the river with its walled riverwalk. The houses were about a mile apart. The view from either house would have been beautiful.

Thomas Birch, Southeast View of “Sedgeley Park,” the Country Seat of James Cowles Fisher, Esq., about 1819.

Thomas Birch, Southeast View of “Sedgeley Park,” the Country Seat of James Cowles Fisher, Esq., about 1819.Sedgley Park was built in 1799, near Philadelphia, by merchant William Cramond. It was one of the earliest Gothic influenced houses in America. A contemporary remarked "The natural advantages of Sedgley Park are not frequently equalled, even upon the banks of the Schuylkill. From the height upon which the mansion is erected it commands an interesting and extensive view. The scenery around is of unusual beauty, but its character is altogether peaceful and quiet."

In 1808, William Birch wrote of John Penn's Solitude in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, The flower garden was distant from the house, reached by a circuitous path which took in as many as possible of the best points of view.

Solitude in Fairmount Park in Philadelphia.

Solitude in Fairmount Park in Philadelphia.Solitude was built as a quiet retreat on the west bank of the Schulykill River. The most English of the country seats built along the river, Solitude was built by John Penn, "the poet," a grandson of William Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania. Today it is in the center of the Philadelphia Zoo, where it serves as administrative headquarters.

.jpg) William Birch, "Solitude in Pennsylvana. Belonging to Mr. Penn." 1809.

William Birch, "Solitude in Pennsylvana. Belonging to Mr. Penn." 1809. Elbridge Gerry described the White House in Washington D. C. in 1813, A door opens at each end, one into the hall, and opposite, one into the terrace from whence you have an elegant view of all the rivers.

1803 White House [View from Blodgett's Hotel to the White House.] by Nicholas King in the Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

1803 White House [View from Blodgett's Hotel to the White House.] by Nicholas King in the Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

+Mrs.+Nathaniel+Brown+(Anna+Porter+Brown).jpg)

Mrs.+John+Edwards+(Abigail+Fowle).jpg)

+Sarah+Prince+Gill,+1764.+(2).jpg)

++Esther+Boardman+Pvt+(1).jpg)

not mentioned elsewhere in period records.

not mentioned elsewhere in period records.