1742-46 attributed to William Dering, Anne Byrd Carter. These brick wall fences had balustrades of wood atop the wall. Brick & stone walls were usually confined to enclosing the grounds of public buildings & grave-yards in early America. Most private homes & gardens were "well paled in" with fences made of wood.

Walls around private gardens in the British American colonies before the 18C are even more difficult to find portrayed in contemporary images.

In Maryland, a painting of Holly Hill from about 1730, depicts a walled brick garden attached to the house. Originally a primitive, two-room, 1 1/2-story frame dwelling constructed in 1698, Holly Hill still exists. Holly Hill with brick wall around its garden about 1730 Maryland Historical Trust

Holly Hill with brick wall around its garden about 1730 Maryland Historical Trust

Its owner Samuel Harrison added the 18 ft. section in 1713, and before his death in 1733, he encased the entire structure in brick. This is probably when the garden was walled-in as well. Holly Hill is one of the few extant examples of the medieval transitional style of architecture used in Maryland during the mid-17th century. Its transition from a primitive frame dwelling to a comfortable brick house reflects a pattern repeated in early Tidewater houses. Holly Hill in Anne Arundel County, Maryland as it exists today

Holly Hill in Anne Arundel County, Maryland as it exists today

Virginia's Royal Governor William Beverley's (1605-1677) home Green Spring, built in 1649, was nearly 97' long and 25' wide. The house & grounds were named for a spring near the house, which a 1680s visitor described as "so very cold that 'twas dangerous drinking the water thereof in Summer-time." The Governor's wife Lady Frances Berkeley described her home in 1677 as "the finest seat in America & the only tollerable place for a Govenour."

Berkeley was an involved farmer & gardener who raised the Virginia cash crop tobacco, of course, plus fields of cotton, flax, hemp & rice. He planted fruit trees by the thousands. A a contemporary reported seeing "Apricocks, Peaches, Mellcotons (peaches grafted onto quince trees), Quinces, Warden (Winter Pears), and such like fruits." He grew grapes to produce his own wines, as well as vegetables and roses.

Although Green Spring was heavily damaged during Bacon's Rebellion in 1676-7, the restored house stood until the last decade of the 18C, when Benjamin Latrobe (1764-1820) painted a watercolor of it in 1797. The watercolor depicts brick curvilinear garden walls planned by Philip Ludwell II (1672-1726), & probably in place, when the property was bequeathed to Philip Ludwell III (1716–1776) in 1727. The Ludwells came to own Green Spring, when widow Lady Frances Berkeley married Phillip Ludwell. Green Spring by Benjamin Latrobe (1764-1820) in 1797. The Baroque curved garden walls replaced a straight-line 100' brick garden wall set at a right angle to the house which led down to the amazingly cold spring and which was probably on the property before 1680-83, when the restored brick house was completed.

Green Spring by Benjamin Latrobe (1764-1820) in 1797. The Baroque curved garden walls replaced a straight-line 100' brick garden wall set at a right angle to the house which led down to the amazingly cold spring and which was probably on the property before 1680-83, when the restored brick house was completed.

Ironically, the other remaining Virginia house built before 1700 having a brick garden wall was Bacon's Castle. It was also known as Allen's Brick House and was used as a headquarters for the attack against Berkeley. The house had the earliest known private formal gardens in the British American colonies. The Jacobean house on the James River was built in 1665, by Arthur Allen. The garden was 195' by 360' divided into 6 large beds each 74' wide & between 90-98' long. The west side of the garden was defined by a brick forcing wall. Bacon's Castle garden in Virginia with brick wall in background. The oldest identified private formal garden in the British American colonies.

Bacon's Castle garden in Virginia with brick wall in background. The oldest identified private formal garden in the British American colonies.

It is more difficult to identify private homes with garden walls in early America from paintings & prints, because private clients of artists overwhelmingly chose portraits of themselves & their families over landscapes throughout most of the period. Fortunately, some of the portraits are depicted on the grounds of the subject's house.

In Virginia, Robert Beverley wrote in 1705, when there were a little over 75,000 folks in his colony, "The private buildings are of late very much improved; several Gentlemen of late having built themselves large Brick Houses." With these brick houses, brick garden walls were common.

In Philadelphia in 1766, there was a court dispute over a contract to build a stone wall around a garden in the city. And in the same year, a 170 acre property containing "a good Garden, walled in with Stone" Chester County, about 20 miles from Lancaster, was advertised for sale in the Pennsylvania Gazette.

One of Philadelphia's richest merchants, Samuel Neave (1707-1774) had his house & business at the corner of Second & Spruce Strees. The property, which contained the main house plus a coach house, stable, garden & greenhouse, had 50' on Second Street & 180' on Spruce Street. It wall all enclosed by brick walls.

Detail 1755 Joseph Blackburn (fl 1753-1763). Isaac Winslow & His Family with a brick wall with finials at the gate in background. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Detail 1755 Joseph Blackburn (fl 1753-1763). Isaac Winslow & His Family with a brick wall with finials at the gate in background. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.Paintings from the early American period depict stone and brick walls in private gardens and grounds, whether real or for affect is difficult to determine. I will try to include only one painting of each type of wall depicted by an artist who used walls in his portraits.

1760 William Williams (1727-1791). Deborah Richmond in front of a sophisticated curved wall.

1760 William Williams (1727-1791). Deborah Richmond in front of a sophisticated curved wall. The home of George Johnson in Alexandria, Virginia, went up for sale the next year. The ad described a dwelling house "upwards of 100 Feet long...a good Garden; the whole enclosed with Pails, and Brick...defended from the Water by a Stone Wall, to which Wall Boats and other small Vessels may come at a moderate Tide."

+San+Fran+Fine+Arts.jpg) c 1763 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Mary Turner (Mrs. Daniel Sargent) in front of a wall.

c 1763 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Mary Turner (Mrs. Daniel Sargent) in front of a wall.Also in 1767, a property of 150 acres at Blue Ball, Pennsylvania, was advertised for sale containing a "stone house...a garden, surrounded with a stone wall."

One traditional commercial garden, Gray's Chatsworth Garden, sat just north of the harbor in Baltimore. Owners converted this old, private garden into an updated public pleasure garden with the addition of serpentine pathways meandering around the tree-lined perimeters of the grounds. The heart of the commercial garden, however, remained an elegant eight-bed falling terrace garden laid out in geometric symmetry during the 1760s, which was completely surrounded by a brick wall.

1767 James Claypoole (1743-1814). Ann Galloway (Mrs Joseph Pemberton) sitting at a low wall.

1767 James Claypoole (1743-1814). Ann Galloway (Mrs Joseph Pemberton) sitting at a low wall.When Philadelphia botanist John Bartram (1699-1777) visited Henry Laurens's (1724-1792) at his town garden in Charleston, South Carolina in 1765, he wrote that Laurens was "making great improvements," and noted that his garden was walled with brick--200 yards long and 150 yards wide.

1771 William Williams (1727-1791). The Wiley Family in front of a tall formal wall.

1771 William Williams (1727-1791). The Wiley Family in front of a tall formal wall. The Virginia Gazette placed a sale notice in 1770, "that beautiful seat and plantation on river, in King & Queen county, whereon John Robinson , Esq; late Treasurer, lived... a large falling garden inclosed with a good brick wall." In 1782, the Marquis de Chastellux (1734-1788), describing William Byrd's Westover in Virginia noted that "the walls of the garden and the house were covered with honeysuckle"

Archaeological excavations have also proven that the 1760s Annapolis town garden of William Paca (1740-1799) was surrounded by a brick wall.

Archaeological excavations have also proven that the 1760s Annapolis town garden of William Paca (1740-1799) was surrounded by a brick wall. +(1763%E2%80%931823)+Yale.jpg) 1787 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Deborah McClenachan (Mrs. Walter Stewart) in front of a curving sophisticated wall.

1787 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Deborah McClenachan (Mrs. Walter Stewart) in front of a curving sophisticated wall..+Sarah+Chew+Elliott+(Mrs.+John+O'Donnell).+Chrysler+Museum+of+Art.+Norfolk,+Virginia..jpg) 1787 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Sarah Chew Elliott (Mrs. John O'Donnell) in front of a curving wall with urns used as finials.

1787 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Sarah Chew Elliott (Mrs. John O'Donnell) in front of a curving wall with urns used as finials. The Pennsylvania Gazette in February of 1791, offered for sale an "extraordinary tract of land for a Gentleman Farmer...county of Montgomery...two orchards of excellent fruit, and a garden of two acres surrounded with a stone wall and terrace."

1800 Felice Corne (1752–1845) Ezekiel Hersey Derby Farm near Salem, Massachusetts. Here is a combination of wooden fences & stone walls.

In 1800, Abigail Adams described the Peacefield, estate of John Adams, Quincy, MA, “the President has authorised me to have a number of Lombardy poplars set out opposite the house near the wall which was new just two years ago. . . he says he will have them extended from the gate. . . to the corner.”

1800 An Over-mantle from the Gardiner Gilman House in Exeter, New Hampshire. This painting shows a combination of wooden fencing & stone walls.

"We are also going to build a wall to the north and west of the garden, beginning at the wash-house and going alongside the orchard...We also need a house for the cattle. We won't stop making bricks until we have 170,000. You can see that we don't lack for work, which takes all my time.

"We are also going to build a wall to the north and west of the garden, beginning at the wash-house and going alongside the orchard...We also need a house for the cattle. We won't stop making bricks until we have 170,000. You can see that we don't lack for work, which takes all my time. As towns developed, brick walls occasionally separated the street front of the house from private rear utility and garden areas.

Wall Separating Public from Private City Spaces in Washington, D.C. in 1817. F Street in the District of Columbia. Baroness Hyde de Neuville.

Wall Separating Public from Private City Spaces in Washington, D.C. in 1817. F Street in the District of Columbia. Baroness Hyde de Neuville.As the influence of Humphrey Repton (1752-1818) and John Claudius Loudon (1783-1843) crossed the Atlantic, high brick walls came into disfavor. The natural landscape designers called for evergreen shrubs or fences which were nearly invisible if at all possible, posts & chains and iron railings were preferred. Repton noted, "It is hardly necessary to say, that the less they are seen the better; and therefore a dark, or as it is called, an invisible green...is the proper colour."

However, English landscape designer Humphrey Repton's (1752–1818) Business Card designed by Thomas Medland ( c.1765 – 1833) depicts Repton's open, "natural" (although well-planned!) landscape design. No fences or walls here.

However, English landscape designer Humphrey Repton's (1752–1818) Business Card designed by Thomas Medland ( c.1765 – 1833) depicts Repton's open, "natural" (although well-planned!) landscape design. No fences or walls here.

+Ezekiel+Hersey+Derby+Farm.jpg)

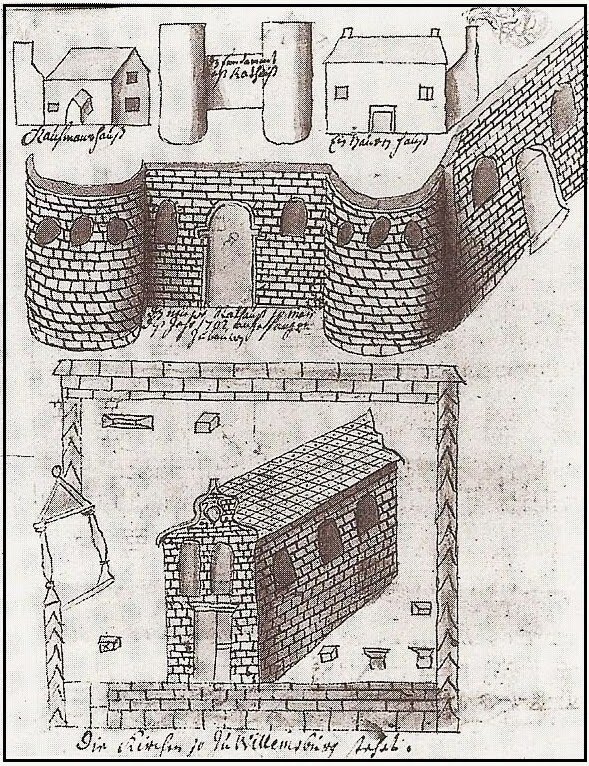

Williamsburg Brick Wall

Williamsburg Brick Wall Brick Wall Around Governor's Palace in Williamsburg, Virginia.

Brick Wall Around Governor's Palace in Williamsburg, Virginia. Powder Magazine at Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia.

Powder Magazine at Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia.