19C Hyde Park by Victor de Grailly (French artist, 1804-1889)

Along the east side of the Hudson River in Dutchess County, New York, Peter (Pierre) Fauconnier (1659–1746), received a 3,600-acre tract of property located on the banks of the river 75 miles north of New York City. He named it Hyde Park after the Governor of New York, Sir Edward Hyde, Lord Cornbury (1661–1723). Peter came to America as the private secretary to Edward Hyde, the 3rd Earl of Clarendon whose cousin, Queen Anne, had appointed him Governor of New York & New Jersey. In 1705.

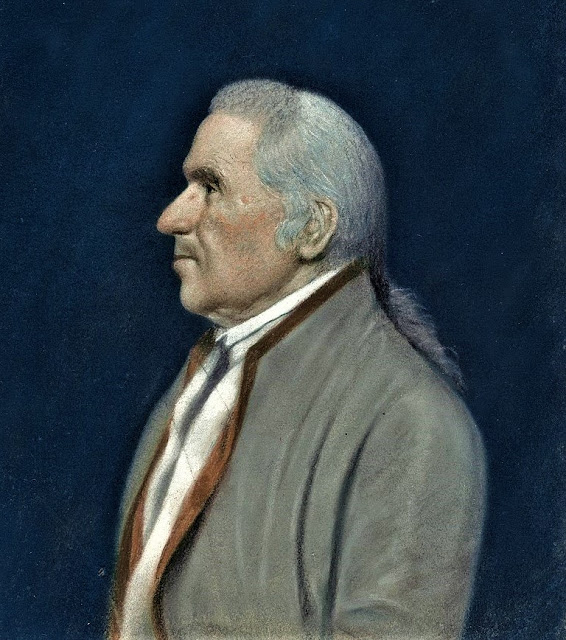

Governor of New York, Sir Edward Hyde, Lord Cornbury (1661–1723)The undeveloped property descended through Fauconnier’s family until 1764. Peter Fauconnier owned Hyde Park from 1705–1746. His daughter Magdalene Fauconnier Valleau 1746–1764 inherited the land at her father's death. In 1764, the river-front land was inherited by his granddaughter, Suzanne Valleau (1720–1784), & her husband, the New York City surgeon Dr. John Bard (1715–1799). At Dr. Bard's death, the property passed on to the son who advised his father, Dr. Samuel Bard (1799–1821.)

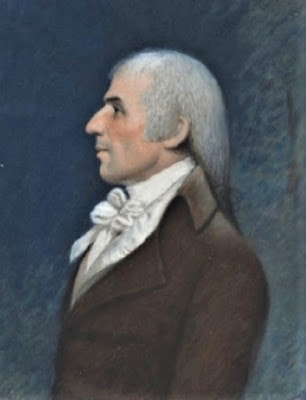

Peter (Pierre) Fauconnier (1659–1746) Private Secretary to Edward Hyde, the Earl of ClarendonDr. John Bard (1715–1799) initially contemplated developing the land that he had inherited into a rural country seat & settling there after retiring from his medical practice in New York City. He received advice on “laying out your grounds” & “planning a pleasure ground” from his son, Samuel Bard (1742–1821), a medical student in Edinburgh who was well versed in contemporary landscape design in Britain & Scotland.

New York surgeon Dr. John Bard (1715–1799), the father in Hyde Park, NYSamuel Bard's, April 1, 1764, letter from Edinburgh to his father Dr. John Bard “I heartily wish I could be with you at laying out your grounds, as I imagine I could be of some assistance, although I may find it impossible to convey my notions upon that subject in writing. From what I have as yet seen, I find those the most beautiful where nature is suffered to be our guide. The principal things to be observed in planning a pleasure ground, seem to me, to be the situation of the ground, & the storms & winds the country is most liable to. By the first, I mean, to distribute my plants according to the soil they most delight in; to place such as flourish most in a warm exposure & dry soil, upon the sunny side of a hill; while such as delight in the shade &moist ground, should be placed in the vallies. By this single precaution, one of the greatest beauties of a garden is obtained, which consists in the health & vigour of the plants which compose it. By considering well the predominant winds & storms of the country, we are directed where to plant our large trees, so that they shall be at once an ornament, & afford a useful shelter to the smaller & more delicate plants. Next I think straight lines should be particularly avoided except where they serve to lead the eye to some distant & beautiful object—serpentine walks are much more agreeable. Another object deserving of attention seems to be, to place the most beautiful & striking objects, such as water, if possible, a handsome green-house, a grove of flowering shrubs, or a remarkably fine tree, in such situations, that from the house they may almost all be seen; but to a person walking, they should be artfully concealed until he suddenly, & unexpectedly, comes upon them; so that by the surprise, the pleasure may be increased: & if possible, I would contrive them so that they should contrast each other, which again greatly increases their beauty. The last thing I should mention, which, indeed, is not the least worthy of notice, is, to throw the flower garden, kitchen, & fruit garden, & if possible, the whole farm, into one, so that they may appear as links of the same chain, & may mutually contribute to the beauties of the whole. If you could send me an accurate plan of the situation of your ground, describing particularly the hollows, risings, & the opportunities you have of bringing water into it, the spot where you intend your house, & the situation of your orchard, I would consult some of my friends here about a proper plan, & I believe I know some who would assist us, & as I cannot obtain your gardener before November, if you sent the plan immediately, I shall be able to return it by him.”

Financial worries led the NYC surgeon to try to sell the land. Only 4 years later, John Bard decided to offer his property for sale, May 12, 1768, New York advertisement offering sale of Hyde Park. “To be sold by the subscriber, living in New-York, either all together, or in distinct farms, a tract of land in the county of Dutchess, & province of New-York, called Hyde Park, or Paulin’s Purchase... containing 3600 acres. The tract in general is filled with exceeding good timber...& abounds in rich swamps; great part of the upland exceeding good for grains or grass, & has on it some valuable improvements...A Large Well -Improved Farm, with a good house, a large new barn, a young orchard of between 500 or 600 apple trees, mostly grafted fruit, & in bearing order; between 30 & 50 acres of rich meadow ground, fit for the scythe; & about 150 acres of upland cleared & in tilling order. There is belonging to the said tract, 3 good-landing-places (particularly one on the above farm) where the largest Albany sloop can lay close to a large flat rock, which forms a natural wharf.” Eventually he decided not to sell the property.

In 1784, after an innovative & esteemed medical career in New York City, Dr. John Bard sought the retiring, pastoral life often longed-for by those of his position & generation. Dr. John Bard had been raised in privileged circumstances, on a farm estate near Philadelphia. He was a close acquaintance of Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) & enjoyed a well-earned professional reputation in medicine, but he felt it was time to retire..

While participating in the cultural activity of New York City, Dr. John Bard had a deep-rooted appreciation for plants & country life. As a medical practitioner, he had a direct involvement with medicinal botany & horticulture. But he longed for the bucolic charms of Hyde Park as an ideal situation, somewhat removed from the basic economic & functional pre-occupation of earlier Hudson River estate owners. In fact, he had on-going financial difficulties & his aspirations for Hyde Park were tempered by the reality of his financial situation. His ornamental landscape improvements were limited.

In 1795, Dr John Bard, then being in his 80th year, gave an address before the state medical society calling attention to the presence of yellow fever in the city, meeting much opposition & some vehemently expressed disapproval, by so doing. Nevertheless, his advice as to treatment of this dread disease-sweating the patient-proved more successful than other methods. In 1798 he gave up his medical practice & retired to Hyde Park where he died, March 30, 1799, at the age of 83.

Dr. Samuel Bard’s Residence. Hyde Park, 1871, watercolor copy of a drawing of c. 1800–23Dr. Samuel Bard (1742-1821) is considered, along with his father Dr. John Bard & Dr. Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia, one of the leading physicians of the colonial & early federal periods. But Bard was also very interested in the study of botany. While his father was more interested in the commercial potential of the family estate in Hyde Park, Samuel indulged his love of plants & botany there. Always looking for agricultural improvements, in 1806 he founded the Dutchess County Agriculture Society, serving as its president for many years & using his position to advocate for the use of clover as a crop & gypsum as a fertilizer. Samuel enjoyed landscaping the more formal grounds of his estate, & he set about planting exotic plants & trees. There is a large Ginko tree on the lawn, that he is said to have planted in 1799, which would make it one of the oldest in North America. The greenhouse he built in 1820 is said to have been the 1st in Dutchess County.

19C Engraving by artist E. White of the Hudson River as seen from Hyde ParkAfter positioning his house, Dr. Samuel Bard laid out the kitchen gardens, & later the greenhouse about 1,000 feet south of the house on a sheltered south facing slope. In selecting this location, Samuel Bard was following his own, early advice to his father, expressed in a 1764 letter, to consider the best advantage of the natural site in placing the various site components: "The principal thing to be observed in planning a pleasure ground, seems to me to be the situation of the ground, & the storms & winds, the country is most liable to."

Said to be Dr Samuel Bard (1742-1821) Actually looks like a young depiction of his father.During the early years of his return to New York, he established a medical school at King’s College. now Columbia University. In 1769 he began lobbying for the city’s 1st public hospital. In Britain, Bard’s friend & mentor, John Fothergill, spearheaded fundraising for the hospital there, & King George III granted it a charter in 1771; but the Revolutionary War intervened. When the hospital was finally completed in 1791, Bard reportedly laid out a botanic garden at the hospital occupying 2 city blocks, in which he cultivated medicinal herbs. Bard also served as one of George Washington's private physicians, saving his life in 1789 by removing a malignancy from his leg. In 1811, College of Physicians & Surgeons was founded in New York, Bard was appointed its president, serving in that capacity until his death in 1821.

+The+Hervey+Converstion+Piece+The+Holland+House+Group.jpg)

+Francis+Vincent,+his+Wife+Mercy,+and+Daughter+Ann,+of+Weddington+Hall,+Warwickshire.jpg)

+The+Thomas+Cave+Family.jpg)

.jpg)

+Mr+and+Mrs+Van+Harthals+and+Son.jpg)

+Henry+Fiennes+Clinton,9th+Earl+of+Lincoln,+with+his+wife+Catherine+and+his+son+George+on+the+great+terrace+at+Oatlands+(2).jpg)

+An+Angling+Party+(perhaps+The+Willyams+Family+at+Carnanton).jpg)

.+The+Grymes+Children-+Lucy+1743-1830,+Philip+1746-1805,+Jno+Randolph+1747-96,+Chas+1748-+.+Virginia+Historical+Society,+Richmond.jpg)

+Richard,+Mary,+and+Peter,+Children+of+Peter+and+Mary+du+Cane+Detail.jpg)

+The+James+Family.jpg)

.jpg)

+The+Mathew+Family+at+Felix+Hall,+Kelvedon,+Essex.jpg)

+A+Group+of+Gentlemen.jpg)

.+The+William+Denning+Family+vine+dog+urn+wall+chair.jpg)

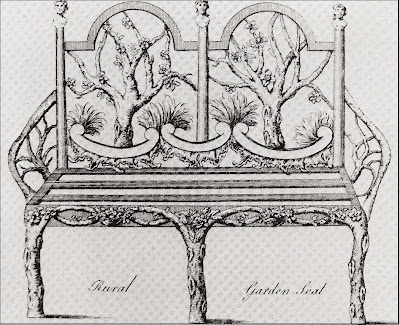

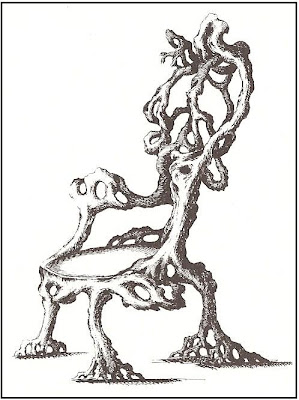

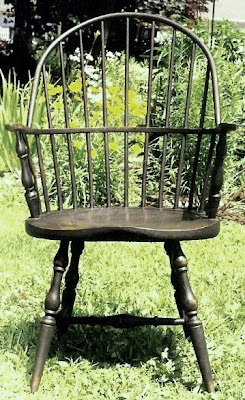

18th century English Woodcut.

18th century English Woodcut.+Detail.+Rice+Hope+Taken+from+One+of+the+Rice+Fields.+South+Carolina.+2.jpg) c 1796. Charles Fraser (1782-1860) Detail of Settee on a Hill at Rice Hope Plantation Taken from One of the Rice Fields. South Carolina.

c 1796. Charles Fraser (1782-1860) Detail of Settee on a Hill at Rice Hope Plantation Taken from One of the Rice Fields. South Carolina.

.+The+Hartley+Family..jpg)

.+The+Enoch+Edwards+Family..jpg)

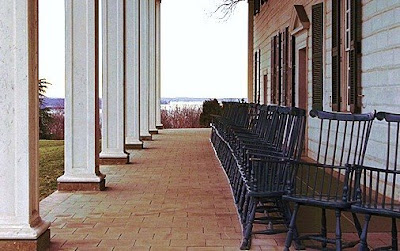

Photo Maryland Historical Society

Photo Maryland Historical Society