Colden was born in New York City, the 5th child of Cadwallader Colden (1688-1776), who was a physician who trained at the University of Edinburgh and became involved in the politics & management of New York after arriving in the city from Scotland in 1718, & his wife Alice Christy Colden, the daughter of a clergyman, brought up in Scotland in an intellectual atmosphere. Daughter Jane Colden was educated at home; & her father provided her with botanical training following the new classification system developed by Carl Linnaeus. His scientific curiosity included a personal correspondence between 1749-1751 with Carolus Linnaeus (1707-1778).

Her father thought women should study botany because of "their natural curiosity & the pleasure they take in the beauty & variety of dress seems to fit them for it." It was true that floral illustrations filled British American colonial homes on English textiles and soft paste & porcelain tableware ordered by the gentry through their factors or sent in the holds of English ships to be sold in local shops.

Moreover, he viewed such study as an ideal substitute for idleness among his female children, when he moved his family to the country in 1729. He believed gardening & botany "an Amusement which may be made agreable for the Ladies who are often at a loss to fill their time." He went so far as to recommend that perhaps from Jane's example "young ladies in a like situation may find an agreable way to fill up some part Of their time which otherwise might be heavy on their hand May amuse & please themselves & at the same time be usefull to others."

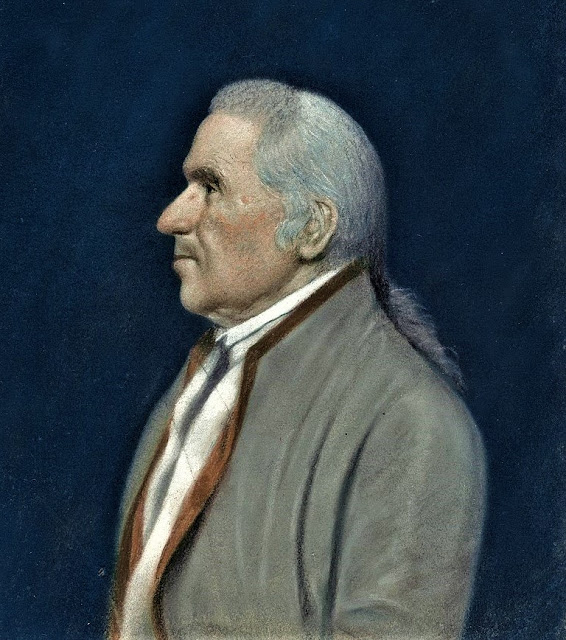

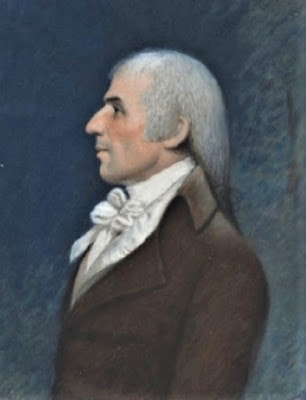

1748-52 John Wollaston (American colonial era painter, 1710-1775) Cadwallader Colden

The family's move to a 3,000-acre estate in Orange County stimulated the botanical interests of both Cadwallader & Jane Colden. Cadwalleder Colden had been the first to apply the system of botanical classification developed by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (Linnaean Taxonomy) to an American plant collection & he translated the text of Linnaeus’ books into English.

A letter of 1755 from Colden to Dutch botanist Jan Gronovius (1666-1762) her father explained. "I have a daughter who has an inclination to reading and a curiosity for natural philosophy or natural History and a sufficient capacity for attaining a competent knowledge. I took the pains to explain to her Linnaeus' system and to put it in English for her to use by freeing it from the Technical Terms which was easily done by using two or three words in place of one. She is now grown very fond of the study and has made such progress in it as I believe would please you if you saw her performance. Tho' perhaps she could not have been persuaded to learn the terms at first she now understands to some degree Linnaeus' characters notwithstanding that she does not understand Latin."

Jane Colden far surpassed her father's idleness theory. She was the 1st scientist to describe the gardenia. She read the works of Carolus Linnaeus (1707-1778) in translation, and she mastered the Linnaean system of plant classification perfectly. She cataloged, described, & sketched at least 400 plants. She actively collected seeds & specimens of New World flora & exchanged them with others on both sides of the Atlantic.

Due to the lack of schools & gardens around the area, her father wrote to Peter Collinson, where he inquired about getting sent "the best cuts or pictures of [plants] for which purpose I would buy for her Tourneforts Institutes & Morison’s Historia plantarum, or if you know any better books for this purpose as you are a better judge than I am I will be obliged to you in making the choice" in order for Jane to continue her studies of botanical sciences.

In addition to obtaining books & illustration samples for his daughter, Cadwallader also surrounded her with like-minded scientists, including Peter Kalm & William Bartram. In 1754, a notable gathering with South Carolina scientist Dr. Alexander Garden (1730-1791) & William Bartram sparked Jane's interests even more & allowed the fruition of the collaboration & friendship between Jane & Garden to flourish. Garden, an active collector of his local flora, later corresponded with Jane, exchanged seeds & plants with her, & instructed her in the preservation of butterflies. Garden wrote in a letter to British naturalist John Ellis (1711-1778) in 1755, that Jane Colden “is greatly master of the Linnaean method, and cultivates it with assiduity.”

Of his daughter, Cadwallader wrote in a 1755 letter to Dr. John Frederic Gronovius, a colleague of Linneaus, that she possessed "a natural inclination to reading & a natural curiosity for natural philosophy & natural history." He wrote that Jane was already writing descriptions of plants using Linnaeus' classification & taking impressions of leaves using a press. In this letter, Cadwallader sought to earn her a position with Dr. Gronovius sending seeds or samples.

On January 20, 1756, Peter Collinson (1694-1768) wrote to John Bartram that "Our friend Colden's daughter has, in a scientific manner, sent over several sheets of plants, very curiously anatomized after this [Linnaeus's] method. I believe she is the first lady that has attempted anything of this nature."

Colden participated in the Natural History Circle where she exchanged seeds & plants with other plant collectors in the American colonies & in Europe. These exchanges within the Natural History Circle encouraged Jane to become a botanist.

Through her father she met & corresponded with many leading naturalists of the time, including Carolus Linnaeus (1707-1778). Carolus Linnaeus knew of Jane's work. He corresponded directly with her father; and in a 1758, letter to British naturalist John Ellis (1711-1778) tells Linnaeus that he will let Jane know "what civil things you say of her." One of her descriptions of a new plant, which she herself called Fibraurea, was forwarded to Linnaeus with the suggestion that he should call it Coldenella, but Linnaeus declined calling it Helleborus (now Coptis groenlandica). Collinson reported to Carolus Linnaeus, "Your system, I can tell you obtains much in America. Mr. Clayton and Dr. Colden at Albany of Hudson's River in New York are complete Professors....Even Dr. Colden's daughter was an enthusiast." He later wrote to Linnaeus, that Jane Colden “is perhaps the first lady that has so perfectly studied your system. She deserves to be celebrated.”

In 1756 Colden discovered the Gardenia & proposed a name after the prominent botanist Garden. In her manuscript she wrote that this plant was without an Order under the Linnaean system. In her description Colden wrote, " The three chives only in each bundle, & the three oval-shap'd bodies on the seat of the flower, together with the seat to which the seeds adhere, distinguish this plant from the hypericums; & I think, not only make it a different genus, but likewise makes an order which Linnaeus has not." However, the name was not allowed because an English botanist named John Ellis had already named the Cape jasmine as Gardenia jasminoides, & was entitled to its use because of the conventions of botanical nomenclature.

1963 Reprint of the British Museum copy of Jane Colden's manuscript

Colden's manuscript, in which she had ink drawings of leaves & descriptions of the plants, was never named. Colden's original manuscript describing the flora of New York has been held in the British Museum since the mid-1800s. Her manuscript drawing consisted only of leaves & these drawings were only ink outlines colored in with neutral tint. Her descriptions were "excellent-full , careful, & evidently taken from living specimens." Colden's descriptions include morphological details of flower, fruit, & plant structure, as well as ways on how to use certain plants for medicinal or culinary purposes. Some of the descriptions include the month of flowering & the habitat where they are found. Latin & common names for the plants are given.

In her section "Observat" (now known as observations) she pointing out to Linnaeus that "there are some plants of Clematis that bear only male flowers, this I have observed with such care that there can be no doubt about it." This shows the long hours she spent doing observations, which were consistent, accurate & replicable.

Colden married Scottish widower Dr. William Farquhar on March 12, 1759. She died in childbirth only 7 years later at the age of 41, along with the newborn. There is no evidence that she continued her botanical work after her marriage.

Her work on plant classification was noted in a Scottish scientific journal in 1770, 4 years after her death. Americans did not become aware of Colden's manuscript until 75 years later, when Almira Lincoln stated that another female botanist before her was the first American lady to illustrate the science of botany. In spite of all of Colden's accomplishments, she was never formally recognized during her lifetime by having a plant named after her. The genus Coldenia is named after her father.

+Cadwallader+Colden.jpg)