Another View of Mt Vernon

Reportedly. the concept of a greenhouse dates back to ancient Egypt, where they were said to grow grapes year-round as early as 4,000 B.C. By 300 B.C. glasshouses were thought to be heated by manure pits. Greenhouses, or earthen "sun pits," may have been invented by Romans or adopted from one of the many conquered countries of Rome. Glass was invented in Ancient Egypt around 3500 B.C. Production of larger, more clear or "aqua" glass panes as windows for churches were more prevalent around the late 7C CE. with Christian Anglo-Saxons.

A medical advisor to Roman Emperor Tiberius (Tiberius was the Emperor who ascended the throne after Augustus) told him that it was necessary for his health, to eat one cucumber (or perhaps a rather tasteless melon) a day. Roman scientists & engineers began brainstorming about how to grow plants year round. By 92 B.C. in Italy, Sergius Orata invented a heating system, with heat passing through flues in the floor. At the time, the specularium, was glazed with mica.

Two agricultural writers, Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella (4CE-70CE) & Gaius Plinius Secundus (Pliny the Elder) (24CE-79CE) who lived during the reign of Tiberius (42 BCE-37 CE), both wrote about the 1st specularia or Roman Greenhouses. In the 1st century CE, these two Roman agricultural writers referred to protogreenhouses (specularia) constructed for the Emperor Tiberius (42 BCE–37 CE), presumably adjacent to his palace, the Villa Jovis on the Isle of Capri.

Pliny wrote (Book 19, 23: 64) that the specularia consisted of beds mounted on wheels which they moved out into the sun and then on wintry days withdrew under the cover of frames glazed with transparent stone (lapis specularis or mica). Apparently the specularia were built to provide, in Pliny’s words, a melon or cucumber for which the Emperor Tiberius had a remarkable partiality; in fact there was never a day on which he was not supplied with it. The Romans came up with the novel plan of growing the plants in wheelbarrows which they took outside during daylight hours and brought in at night. Unfortunately, sometimes this was not sufficient heat, and the plants died. So the intrepid gardeners began using 2 different materials to cover the plants. One was oiled cloth, known as specularia, and the other was thin transparent sheets of the rock, selenite. Eventually, they made their lives easier and built cucumber houses using specularia or selenite as a roof.

By 380, Italians were using hot water filled trenches to grow roses indoors. In the 1600s Europeans were using southern facing glass, stoves & manure to grow winter crops of citrus fruits. The growing sheds were called orangeries & later were heated with carts filled with burning coal.

In Korea, one of the earliest records of the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty in 1438 confirms growing mandarin trees in a Korean greenhouse during the winter and installing a heating system. The Koreans built structures to grow plants that they heated using a concept called ondol. This was a method of under-floor heating, and they grew mandarin oranges together with other plants in their greenhouses. This practice developed from 1438 to 1450 & was described in detail by European explorers.

In the 13C, greenhouses were built in Italy to house the exotic plants that explorers brought back from the tropics. They were originally called giardini botanici (botanical gardens). The concept of greenhouses also appeared in the Netherlands & then England in the 17C, along with the plants.

One of the earliest greenhouses was built in Holland, by French botanist Jules Charles de Lecluse (1526-1609) in 1599 for the cultivation of tropical & medicinal plants. Charles L'Ecluse was botanist, also known as Carolus Clusius, aided the science of botany by cultivating exotic & fungal plants, including the potato (1588). L'Ecluse also wrote extensively on the subject of botany. He was appointed director of the emperor's garden in Vienna, Austria, from 1573-87 & in 1593 was made professor of botany at Leyden in the Netherlands. L'Ecluse 1st studied law in Belgium, then medicine in Germany; he received a medical degree in 1555.

Originally built on the estates of the rich, greenhouses spread across Europe to the universities with the growth of the science of botany. The British sometimes called their greenhouses conservatories, since they conserved the plants. The French often called their 1st greenhouses orangeries, since they were used to protect precious orange trees from freezing. As pineapples became popular, pineries, or pineapple pits, were built. In Baltimore, a pinery was alternately called a stove house. In British colonial America, the mention of an early Boston greenhouse calls it a hothouse. The more generic terms “greenhouse” and “conservatory” came into general use as time passed, as did a few more specific names referring to contents, such as “pinery, peachery, grapery & vinery.”

Much like today, the 18C colonial greenhouse was a glass-windowed structure of wood or brick or stone in which tender plants were reared & preserved. Revolutionary iron & glass greenhouses would appear in the first half of the 19C allowing more light into the structures.

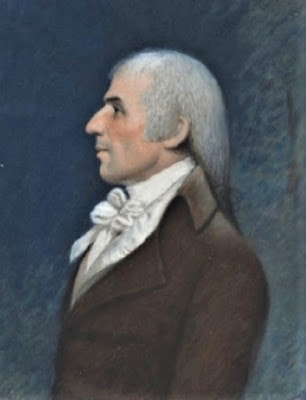

Virginian William Byrd II (1674-1768) painted by Hans Hysing 1724

Virginian William Byrd II (1674-1768) painted by Hans Hysing 1724Early in 18C Pennsylvania, botanist John Bartram (1699-1777) wrote to English botanist Peter Collinson (1674-1768), on July 18, 1740, about Colonel William Byrd's (1674-1744) grounds at Westover in Virginia. "Colonel Byrd is very prodigalle...new Gates, gravel Walks, hedges, and seddars cedars finely twined and a little green house with two or three orange trees...he hath the finest seat in Virginia."

Twenty years later, John Bartram wrote to Peter Collinson in 1760, “Dear friend, I am going to build a greenhouse. Stone is got; & hope as soon as harvest is over to begin to build it, to put some pretty flowering winter shrubs, & plants for winter’s diversion; not to be crowded with orange trees, or those natural to the Torrid Zone, but such as will do, being protected from frost.”

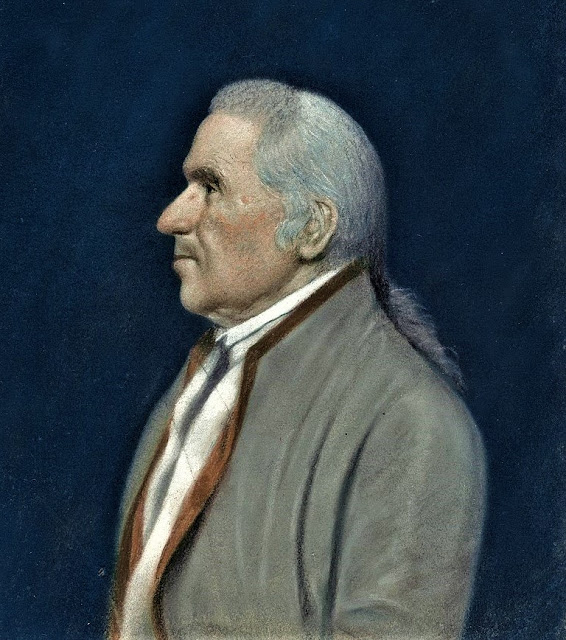

Peter Collinson 1694-1768

Peter Collinson 1694-1768John Bartram was much more than just a commentator on the homes of colonial gentry, but he certainly would have been intrigued by the possibilities of Byrd's early greenhouse. Born in Darby, Pensylvania, son a Quaker farmer, Bartram became the most important botanist in the colonies. His son William Bartram (1739-1823) helped him collect, replant, & ship his specimens. In 1728, John Bartram established a botanic garden at Kingsessing on the west bank of the Schuylkill, near Philadelphia, where he collected & grew native plants. His correspondence with Peter Collinson, led to the introduction of many American trees & plants into Europe.

Charles Willson Peale's 1808 depiction of Botanist William Bartram (1739-1823) son of John Bartram (1699-1777)

Charles Willson Peale's 1808 depiction of Botanist William Bartram (1739-1823) son of John Bartram (1699-1777) Greenhouses in Europe filled with Bartram's Boxes of American plants. His plant specimens & seeds traveled across the Atlantic to the gardens & greenhouses of Philip Miller, Linnaeus, German botanist Dillenius (1687-1747), & Dutch botanist Gronovius (1686-1762); and he assisted Linnaeus' student Swedish Pehr Kalm (1716-1779) during his collecting trip to North America in 1748-1750. Although Bartram never visited Britain, in 1765, he was appointed Botanist to King George III. Linnaeus called him "the worlds greatest botanist." Bartram traveled from Lake Ontario in the north, to Florida in the south and the Ohio River in the west. His Diary of a Journey through the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida, a trip taken from July 1, 1765, to April 10, 1766, was published.

Not far from Bartram's nursery just outside of Philadelphia, John Smith described the plantation owned by the family of William Penn (1644-1718) at Springettesbury Manor in 1745, “In the afternoon, the weather being so agreeable, John Armitt & I rode to Charles Jenki’s ferry on Schuykill. We ran & walked a mile or two on the ice. On our way thither we stopped to view the proprietor’s green-house, which at this season is an agreeable sight; the oranges, lemons & citrons were, some green, some ripe, some in blossom.” Springettesbury Manor had been named in honor of William Penn's first wife Gulielma Maria Springett (1644–1694).

Ten years later, Daniel Fisher also described the Pennsylvania Proprietor's greenhouse, "What to me surpassed every thing of the kind I had seen in America was a pretty bricked Green House, out of which was disposed very properly in the Pleasure Garden, a good many Orange, Lemon, and Citrous Trees, in great profusion loaded with abundance of Fruit and some of each sort seemingly ripe then." Bartram traveled South in the colonies through Charleston several times, where greenhouses were used to entice real estate buyers.

In the South Carolina Gazette, November 14, 1748, a house-for-sale advertisement noted, "TO BE SOLD...Dwelling-house...also a large Garden, with two neat Green Houses for sheltering exotic Fruit Trees, and Grape-Vines."

Exotic plants captured the fancy of colonials early in the century; and by the end of the 18th-century, formal botanical gardens dotted the Atlantic coast. These were both outdoor and indoor, public and private garden areas, where proud collectors displayed a variety of curious plants for purposes of science, education, status, and art.

Josiah Quincy (1744-1775), who kept a journal as he traveled South from Boston for his health in 1773, was also impressed with a greenhouse, when he visited Philadelphia on May 3, 1773, and noted, "Dined with the celebrated Pennsylvania Farmer, John Dickenson Esqr, at his country seat about two and one-half miles from town...his gardens, green-house, bathing-house, grotto, study, fish pond...vista, through which is distant prospect of Delaware River." John Dickinson (1732-1808), who was actually an attorney trained at Middle Temple, had married Mary Norris, daughter of Isaac Norris, Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly, and moved to the Norris estate of Fairhill, near Germantown. There he wrote, under the pseudonym "A Farmer,"12 essays against the Stamp Acts.

1773 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Mary Norris (Mrs. John Dickinson) daughter Sally.

1773 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Mary Norris (Mrs. John Dickinson) daughter Sally.Visiting English agricultural writer Richard Parkinson (1748-1815) stopped at John O'Donnell's (1743-1805) estate named Canton near Baltimore, in 1798. Irishman John O'Donnell had grown wealthy by sending the first ship into China in 1785, for trade goods to sell in America. Parkinson wrote that O'Donnell had, "a very handsome garden in great order, a most beautiful greenhouse and hot house...a very magnificent place for that country."

1787 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Sarah Chew Elliott (Mrs. John O'Donnell) in her garden in front of a curving wall with urns used as finials.

1787 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Sarah Chew Elliott (Mrs. John O'Donnell) in her garden in front of a curving wall with urns used as finials.In 1793 Massachusetts, Boston merchant Joseph Barrell (1739-1804) was ordering plants & a gardener from Britain for his new Pleasant Hill greenhouse, "I want a person that understands green house plants...you will send the trees by the same opportunity the gardener comes that he may attend them on the passage." Wishing for more land outside of Boston to try new gardening styles & modern farming techniques, Barrell purchased 211 acres of land across the Charles River in Charlestown, where he created a ferme ornée. Charles Bulfinch designed the house & grounds, one of his 1st commissions.

John Singleton Copley (1738–1815) Joseph Barrell c 1767

John Singleton Copley (1738–1815) Joseph Barrell c 1767 John Singleton Copley (1738–1815) Hannah Fitch (Mrs Joseph Barrell) c 1771

John Singleton Copley (1738–1815) Hannah Fitch (Mrs Joseph Barrell) c 1771In Deborah Logan's journal, she mentioned that in 1799 Philadelphia, William Logan had a "Green house in town, as well as a good one (at Stenton). He had many rare and beautiful plants: indeed the large and fine orange and lemon trees which now ornament Pratt's greenhouses at Lemon Hill were originally of his raising." William Logan (1717–1776) was the son of William Penn's secretary James Logan who became a Philadelphia Mayor & Supreme Court Justice. William inherited Stenton in 1751, and he used it as his country seat, while living in Philadelphia.

In the same year, English born seedsman and nursery owner William Booth of Baltimore advertised in the Federal Gazette and Baltimore Advertiser:" To Botanists, Gardeners and Florists, and to all other gentlemen, curious in ornamental, rare exotic or foreign plants and flowers, cultivated in the greenhouse, hot-house, or stove, and in the open ground. A large and numerous variety of such rarities is now offered for sale...After reserving a general and suitable stock, he had to spare a well assorted and great variety of those things comprising a beautiful collection, sufficient to decorate, furnish, and ornament a spacious or handsome greenhouse at once...please apply to John Cummings, at the alms-house, Messrs. David and Cuthbert Landreth, gardeners and nursery-men... Now is as good time and proper season to build a green-house, and to remove plants."

Many of Booth's clients and contemporaries in the Chesapeake were becoming excited about collecting and displaying non-native varieties of plants. In his diary, silversmith, clockmaker, & gardener William Faris (1728-1804) noted in Annapolis that his neighbor Dr. Upton Scott (1722-1814) was, "fond of botany and has a number of rare plants and shrubs in his greenhouse and garden." The practical Faris used his cellar as his greenhouse.

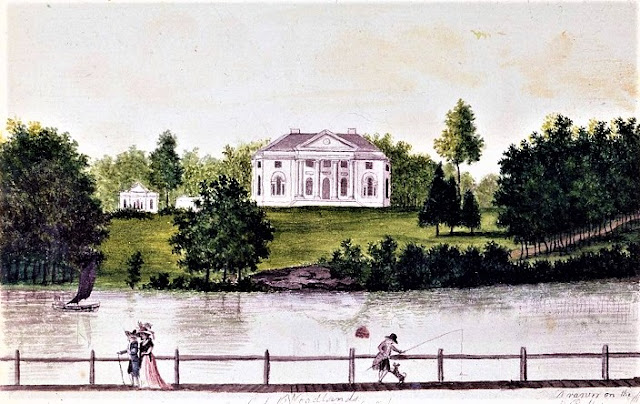

Some gardeners & plant collectors were obsessed with showing off their unusual plant collections to visitors. Philadelphian William Hamilton (1745-1813) constructed an enormous greenhouse flanked by 2 hothouses to cultivate his expanding collection of exotics at his Schuylkill River estate, The Woodlands. In 1767, 22-year-old William Hamilton moved from the family's large house at Bush Hill, in Philadelphia to this more remote site at a bend in the Schuylkill River. Here he would spend his life in the manner of an English country gentleman, cultivating his interests in architecture, landscape design, and botany.

In fact both Jefferson and Lewis corresponded with Hamilton. From St. Louis in March of 1804 Lewis sent Jefferson some cuttings from an Osage orange tree, asking him to forward part of them to Hamilton. Upon departing Fort Mandan in the spring of 1805 he sent a box containing 60 plant specimens to Jefferson, who sent them to the American Philosophical Society with a request to send them to Hamilton for planting. In early January of 1807 Jefferson wrote to the Philadelphia botanist and gardener Bernard McMahon that Lewis had returned to Washington City with "a considerable number of seeds," which the President recommended McMahon share equally with Hamilton. It seems likely that Lewis delivered them in person. We know of only 19 of the species that were represented in this later collection, including black, yellow, and red currant, "Ricara Currant," and a "large species of Tobacco." On 3 February 1808 Hamilton informed Jefferson that not all the seeds he received had germinated as yet, but he had succeeded in growing "the yellow wood, or Osage apple, seven or eight sorts of gooseberries currants & one of his kind of aricarara tobacco."

On July 25, 1803, David Hosack mentioned in a letter to Dr. Thomas Parke, Hamilton's greenhouse at The Woodlands, “I duly received the plans of Mr. Hamiltons green and hot houses. My greenhouse [exclusive of the hothouses] is now finishing - it will not differ very individually from Mr. Hamiltons...I hope William Hamilton will have duplicates of rare and valuable plants - I will supply him anything I possess.”

Thomas Jefferson wrote on March 1, 1808, in a letter to William Randolph, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA “...my green house is only a piazza adjoining my study, because I mean it for nothing more than some oranges, Mimosa Farnesiana & a very few things of that kind. I remember to have been much taken with a plant in your green house, extremely odoriferous, & not large.”

Gilbert Stuart (Early Americn artist, 1755-1828). Rosalie Stier Calvert (1778 -1821) in 1804

Gilbert Stuart (Early Americn artist, 1755-1828). Rosalie Stier Calvert (1778 -1821) in 1804There are early references to orangeries in England, where John Evelyn wrote in his diary on 4 July 1664, "The orangerie and aviarie handsome, and a very large plantation about it." Another reference appears in the 1705 London Gazette, "The Mansion-House, called Belsize, ...with...a fine Orangarie, is to Lett."

In America in 1790, Thomas Lee Shippen, describing Stratford Hall in Virginia, to his father reported, "It was with great difficulty that my Uncles, who accompanied me, could persuade me to leave the hall to look at the gardens, vineyards, orangeries and lawns which surround the house."

Kirk Boott wrote of his own home on April 15, 1806, in Boston, MA “...my Greenhouse has flourished beyond my expectation, & what pleases me much, I have found my skill equal to the care of it. Lettuces in abundance I have preserved, & have had fine Sallads thro’ the Winter.”

"The Greenhouse and Conservatory have been generally considered as synonimous; their essential difference is this: in the greenhouse, the trees and plants are either in tubs or pots, and are planted on stands or stages during the winter, till they are removed into some suitable situation abroad in summer.

"In the conservatory, the ground plan is laid out in beds and borders, made up of the best compositions of soils that can be procured, three or four inches deep. In these the trees or plants, taken out of their tubs or pots are regularly planted, in the same manner as the plants in the open air.

"This house is roofed, as well as fronted with glass-work, and instead of taking out the plants in summer, as in the Greenhouse, the whole of the glass roof is taken off, and the plants are exposed to open air."

1799 Ann Ogle (Mrs. John Tayloe III) and daughters Rebecca and Henrietta.

1799 Ann Ogle (Mrs. John Tayloe III) and daughters Rebecca and Henrietta.The Minute Book of John Tayloe III (1770-1828) noted on August 2, 1812 at his country seat Mount Airy in Richmond County, Virginia, "Gardeners attending to the Greenhouse at Mt. Airy." Tayloe's city residence was Octogon House in Washington D. C.

Wye House (18C greenhouse with hot air duct system, still owned by descendants of Edward Lloyd) Copperville, Talbot County, Maryland. Photo by Janet Blyberg.

Wye House (18C greenhouse with hot air duct system, still owned by descendants of Edward Lloyd) Copperville, Talbot County, Maryland. Photo by Janet Blyberg.By the early 19C in the new republic, gentlemen were building greenhouses, conservatories, orangeries, hot houses, pineries, and stove houses to grow tender plants for their food value and to impress their neighbors. Some even had their portraits painted holding their favorite tender potted plants.

1801 Rubens Peale with Geranium by Rembrant Peale (1778-1860)

+Rubens+Peale+with+Geranium.jpg)

+The+Hervey+Converstion+Piece+The+Holland+House+Group.jpg)

+Francis+Vincent,+his+Wife+Mercy,+and+Daughter+Ann,+of+Weddington+Hall,+Warwickshire.jpg)

+The+Thomas+Cave+Family.jpg)

.jpg)

+Mr+and+Mrs+Van+Harthals+and+Son.jpg)

+Henry+Fiennes+Clinton,9th+Earl+of+Lincoln,+with+his+wife+Catherine+and+his+son+George+on+the+great+terrace+at+Oatlands+(2).jpg)

+An+Angling+Party+(perhaps+The+Willyams+Family+at+Carnanton).jpg)

.+The+Grymes+Children-+Lucy+1743-1830,+Philip+1746-1805,+Jno+Randolph+1747-96,+Chas+1748-+.+Virginia+Historical+Society,+Richmond.jpg)

+Richard,+Mary,+and+Peter,+Children+of+Peter+and+Mary+du+Cane+Detail.jpg)

+The+James+Family.jpg)

.jpg)

18th Century English Woodcut

18th Century English Woodcut

+The+Mathew+Family+at+Felix+Hall,+Kelvedon,+Essex.jpg)

+A+Group+of+Gentlemen.jpg)

.+The+William+Denning+Family+vine+dog+urn+wall+chair.jpg)

18th century English Woodcut.

18th century English Woodcut.+Detail.+Rice+Hope+Taken+from+One+of+the+Rice+Fields.+South+Carolina.+2.jpg) c 1796. Charles Fraser (1782-1860) Detail of Settee on a Hill at Rice Hope Plantation Taken from One of the Rice Fields. South Carolina.

c 1796. Charles Fraser (1782-1860) Detail of Settee on a Hill at Rice Hope Plantation Taken from One of the Rice Fields. South Carolina.

.+The+Hartley+Family..jpg)

.+The+Enoch+Edwards+Family..jpg)

Photo Maryland Historical Society

Photo Maryland Historical Society