Friday, June 19, 2020

1764 Plants in 18C Colonial American Gardens - Virginian John Randolph (727-1784) - Mint

A Treatise on Gardening Written by a native of this State (Virginia)

Author was John Randolph (1727-1784)

Written in Williamsburg, Virginia about 1765

Published by T. Nicolson, Richmond, Virginia. 1793

The only known copy of this booklet is found in the Special Collections of the Wyndham Robertson Library at Hollins University in Roanoke, Virginia.

Mint

Mint, Mentha, from mens, the mind, because it strengthens'the mind. These should be planted in the spring, by parting the roots or cuttings, and planted six inches asunder; otherwise the roots mat into one another, and destroy themselves in three years.

.

Thursday, June 18, 2020

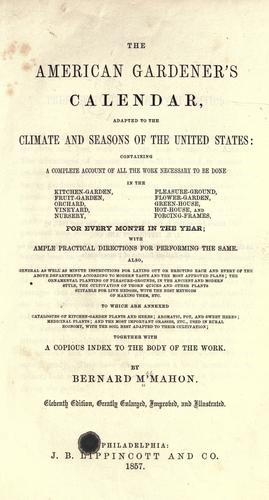

Bernard McMahon, Pioneer American Gardener

Bernard McMahon, Pioneer American Gardener

"McMahon's chief legacy was his American Gardener's Calendar, the most comprehensive gardening book published in the United States in the first half of the nineteenth century; popularity and influence can be gauged by the eleven editions that were printed up to 1857. The 648-page Calendar was modeled on a traditional English formula, providing month-by-month instructions on planting, pruning, and soil preparation for the various horticultural divisions -- the Kitchen Garden, Fruit Garden, Orchard, Nursery, etc.

"McMahon borrowed extensively from English works, especially those of Philip Miller and particularly from John Abercrombie, author of Every Man his own Gardener, first published in York in 1767 under the name of Thomas Mawe, at the time a more recognizable figure. McMahon's sixty-three page General Catalogue of recommended garden plants (3,700 species) was unrealistically biased in favor of traditional Old World species. It is doubtful whether a majority of them were then found in the United States; one also wonders how many American gardeners actually possessed an English-style Fruit Garden, much less a Greenhouse or Hothouse, in 1806? A renowned English contemporary, J. C. Loudon, suggested the derivative character of the Calendar in 1826: "We cannot gather from the work any thing as to the extent of American practice in these particulars."

"McMahon borrowed extensively from English works, especially those of Philip Miller and particularly from John Abercrombie, author of Every Man his own Gardener, first published in York in 1767 under the name of Thomas Mawe, at the time a more recognizable figure. McMahon's sixty-three page General Catalogue of recommended garden plants (3,700 species) was unrealistically biased in favor of traditional Old World species. It is doubtful whether a majority of them were then found in the United States; one also wonders how many American gardeners actually possessed an English-style Fruit Garden, much less a Greenhouse or Hothouse, in 1806? A renowned English contemporary, J. C. Loudon, suggested the derivative character of the Calendar in 1826: "We cannot gather from the work any thing as to the extent of American practice in these particulars."

"Nevertheless, Mahon's Calendar appealed to Jefferson because it attempted to deal with some of the unique problems of American gardening. McMahon made a concerted effort to break away from English traditions in the way he celebrated the use of native American ornamentals, championed large-scale cider and seedling peach orchards that could be grazed with livestock, and admitted the harsh realities of eastern North America's continental climate.

"McMahon reinforced Jefferson's custodial pride in the culture of American plants. It was in the Calendar that American gardeners were first urged to comb the local woodlands and fields for "the various beautiful ornaments with which nature has so profusely decorated them." Wildflowers, according to McMahon, were particularly suited for the hot, humid summer when American gardens "are almost destitute of bloom." McMahon continued, "Is it because they are indigenous that we should reject them? What can be more beautiful than our Lobelias, Asclepias, Orchis, and Asters? In Europe plants are not rejected because they are indigenous; and yet here, we cultivate many foreign trifles, and neglect the profusion of beauties so bountifully bestowed upon us by the hand of nature."

"McMahon's Calendar also included the first American essay on landscape design. Titled, "Ornamental Designs and Plantings," this eighteen-page treatise may have inspired Jefferson's design schemes for the Roundabout flower border and oval beds on the West Lawn at Monticello. Following the dictates of English landscape designer Humphrey Repton, McMahon promoted the new, informal style of naturalistic gardening. He urged his readers to "consult the rural disposition in imitation of nature" that would include "winding walks, all bounded with plantations of trees, shrubs, and flowers in various clumps." The use of broad lawns, thickets, and irregularly-shaped flower beds were further ways of banishing traditional, formal landscape and garden geometry. Few American gardening books have so thoroughly combined landscape gardening and horticulture like Bernard McMahon's The American Gardener's Calendar. McMahon's writings provided a foundation for the popularity of Andrew Jackson Downing, generally considered the father of landscape design in this country.

"Who was Bernard McMahon? Information on this gardening pioneer is scanty. Born in Ireland "of good birth and fortune," he moved to Philadelphia in 1796 to avoid political persecution and soon established a seedhouse and nursery business by 1802. In that year (or perhaps in 1803) he published a broadsheet "A CATALOGUE OF GARDEN GRASS, HERB, FLOWER, TREE & SHRUB-SEEDS, FLOWER ROOTS, ETC." that included 720 species and varieties of seed. Considered the "first seed catalogue" published in this country, it is a landmark index to the plants introduced and cultivated in the United States at that time. For instance, this list supplements the documented plantings of Jefferson in the yearly plantings of the flower gardens at Monticello. In 1804 another catalogue of thirty pages, mostly devoted to native American seeds, was published.

"Beginning in 1806 McMahon was trusted with seeds and plants collected from the Lewis and Clark expedition. Jefferson insisted that these new discoveries were the property of the expedition and of the federal government, so McMahon was forced, perhaps rightfully so, to grow these novelties under restriction in a quarantine-like situation. As well, sticky complications and fierce personal rivalries arose over the description, illustration, and release of the plants, which included golden currant (Ribes aureum), snowberry (Symphoricarpus albus), and Osage orange (Maclura pomifera): as many as twenty-five undescribed species. Botanical historian and scholar, Joseph Ewan, observed, "It must have tried his soul on occasion to have to weed and water these plantings through the years without realizing thereby either the aura of publicity for his nursery or the personal satisfaction of guardianship for what were precious discoveries of new genera and species eventually announced, not in America, but in England!"

"In 1808 McMahon purchased twenty acres for his nursery and botanic garden that would enable him to expand his business. A steady stream of correspondence, thirty-seven letters, passed between him and President Jefferson until 1816, when McMahon died at his "Botanical Garden, called Upsal." The nursery business was left to his wife, who, according to Ewan, "conducted it under difficulties that would have appalled most women." Their son, Thomas P., was also involved in the business, as well as further publications of the Calendar.

"The most vivid written document to survive regarding McMahon and his Philadelphia seedhouse was written by John Jay Smith, editor of The Horticulturist, for the eleventh edition of the Calendar in 1857. Smith's memoir suggests the ferment of botanical and horticultural activity at the time:

"Many must still be alive who recollect its [the store's] bulk window, ornamented with tulip-glasses, a large pumpkin, and a basket or two of bulbous roots; behind the counter officiated Mrs. M'Mahon, with some considerable Irish accent, but a most amiable and excellent disposition. Mr. M'Mahon was also much in the store, putting up seeds for transmission to all parts of this country and Europe, writing his book, or attending to his correspondence, and in one corner was a shelf containing a few botanical or gardening books; another contained the few garden implements, such as knives and trimming scissors; a barrel of peas, and a bag of seedling potatoes, an onion receptacle, a few chairs, and the room partly lined with drawers containing seeds, constituted the apparent stock in trade of what was one of the greatest seed houses then known in the Union.

"Such a store would naturally attract the botanist as well as the gardener, and it was the frequent lounge of both classes, who ever found in the proprietors ready listeners as well as conversers. They were rather remarkable, and here you would see Nuttall, Baldwin, Darlington, and other scientific men, who sought information or were ready to impart it."

"A portrait of Bernard McMahon by an unidentified Philadelphia artist was revealed to us by a McMahon descendent, Betty Carter Fort of Washington, D.C. Although it is impossible to verify that the portrait is indeed our pioneer American nurseryman, the force of his surprisingly powerful gaze suggests a certain wily intelligence. Here, we suspect, is a sensibility worthy of the responsibility for the Lewis and Clark botanical collection; the authoritarian visage of the author of America's best gardening book of the early nineteenth century."

Wednesday, June 17, 2020

19C Women & Gardens - American Lydia Field Emmet (1866-1952)

Lydia Field Emmet (American artist, 1866-1952) Grandmother's Garden

Lydia Field Emmet (American artist, 1866-1952) Flowers along the White Picket Fence

Lydia Field Emmet (American artist, 1866-1952) Two Women in a Garden

Lydia Field Emmet (1866 -1952) was an American artist best known for her work as a portraitist. Emmet exhibited widely during her career, and her paintings can now be found hanging in the White House, and many prestigious art galleries, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Lydia Field Emmet (American artist, 1866-1952) Flowers along the White Picket Fence

Lydia Field Emmet (American artist, 1866-1952) Two Women in a Garden

1764 Plants in 18C Colonial American Gardens - Virginian John Randolph (727-1784) - Lettuce

A Treatise on Gardening Written by a native of this State (Virginia)

Author was John Randolph (1727-1784)

Written in Williamsburg, Virginia about 1765

Published by T. Nicolson, Richmond, Virginia. 1793

The only known copy of this booklet is found in the Special Collections of the Wyndham Robertson Library at Hollins University in Roanoke, Virginia.

Lettuce

Lettuces, Lactuca,from lac, milk, they being of a milky substance, which is emitted when the stalk is broken. There is a common garden Lettuce which is sown for cutting young and mixing with other small salads, and is the Cabbage Lettuce degenerated, as all seed will do that is saved from .a lettuce that has not Cabbage close by. These may be sown at any season of the year. The Cabbage Lettuce should be sown every month to have a succession, and drawn, as all the sorts ought to be, to stand at different distances, and these should stand about ten inches asunder, and by replanting those that are drawn, they will head later than those which stand, by which means you may have a succession. This sort of Lettuce is the worst of all the kinds in my opinion. It is the most watery and flashy, does not grow to the size that many of the other sorts will do, and very soon runs to seed. When I Say the seed is to be sown every month, I mean only the growing months, the first of which February is esteemed, and August the last. In August you should sow your last crop, about the beginning of the month, and in October transplant them into a rich border, sheltered from the weather by a box with a lid, which should be opened every morning and closed in the evening, and in the month of February you will have fine loaf lettuces; a lettuce is a hardy plant, particularly the Dutch brown, and will stand most of our winters, if covered only with peas, asparagus haum, mats or straw. In order to have good seed, you should make choice of some of your best Cabbage, and largest plants, which will run up to seed, and should be secured by a stick, stuck into the ground; and different sorts should not stand together, for the farina will intermix and prejudice each other, and none but good plants should be together for seed; experience has shown that the bad will vitiate the good, and the seed from the plants that have stood the winter are best. The seed is good at two years old, and will grow at three, if carefully preserved.

The Siiesia, imperial white, and upright Cos Lettuce, should be sown in February or beginning of March, and should he drawn so as to stand, Miller says, eighteen inches at least distance from each other, but thinks two feet much better.

The Egyptian green Cos, and the Versailles upright Cos and Silesia, are most esteemed in England as the sweetest and finest, though the imperial wants not its advocates. I, for my own part, give it the preference for three reasons, the first is, that it washes by far the easiest of any; second, that it will remain longer before it goes to seed than any other, except the Dutch brown; and lastly, that it is the crispest and most delicious of them all.

The Dutch Brown, and green Capuchin are very hardy, will stand the winters best, and remain in the heat of summer three weeks longer than any other before they go to seed, which renders them valuable, though they are not so handsome or elegant a Lettuce as any of the former. They may be sown as the common garden Lettuce in the spring, and in August as before.

The Aibppo and Roman Lettuce cabbage the soonest of any, and may be propagated for that reason; the first is a very spotted Lettuce: Col. Ludwell gave me some of the seed, but it did not please me so well as the other more common sorts; all the seed on a stalk will not ripen at the same time, so you must cut your stalk when some of the first seed are ripe. Mice are very fond of the seed. Some Lettuces show a disposition to head without assistance^ these should not be touched, but where they throw their leaves back, they should be tied up, though that restrains them from growing to a great size. They will not flourish but in richl and, and if dunged, the dung should not be very low, because the root of a lettuce will not go down so low as the dung is commonly spitted into the ground. The time for gathering the seed is when the plants show their down. Transplanting, it is said, contributes towards cabbaging; but they will cabbage, from my experience, every bit as well without. By transplanting you retard the growth, and by that means may have a succession.

Tuesday, June 16, 2020

Tho Jefferson (1743-1824) Writes about Gardening

Thomas Jefferson by Tadeusz Andrzej Bonawentura Kosciuszko (1746 - 1817)

1809 September 22. (Jefferson to Benjamin Rush). "I am endeavoring to recover the little I once knew of farming, gardening Etc. and would gladly now exchange any branch of science I possess for the knolege of a common farmer. too old to learn, I must be contented with the occupation & amusement of the art. already it keeps me so much without doors that I have little time to read, & still less to write."

Benjamin Rush (1745-1813) was a signer of the United States Declaration of Independence & a civic leader in Philadelphia, where he was a physician, politician, social reformer, humanitarian, & educator & the founder of Dickinson College. Rush attended the Continental Congress. He served as Surgeon General of the Continental Army & became a professor of chemistry, medical theory, & clinical practice at the University of Pennsylvania. Rush was a leader of the American Enlightenment & an enthusiastic supporter of the American Revolution. He was a leader in Pennsylvania's ratification of the Constitution in 1788. He opposed slavery, advocated free public schools, & sought improved education for women & a more enlightened penal system. As a leading physician, Rush had a major impact on the emerging medical profession. As an Enlightenment intellectual, he was committed to organizing all medical knowledge around explanatory theories, rather than rely on empirical methods.

Research & images & much more are directly available from the Monticello.org website.

Monday, June 15, 2020

Garden Walls by American Winslow Homer 1836-1910

Winslow Homer (American artist, 1836-1910) Girl and Laurel

Winslow Homer was an American artist. He is considered one of the foremost painters in 19C America and a preeminent figure in American art. Largely self-taught, Homer began his career working as a commercial illustrator.

"The sun will not rise or set without my notice, and thanks." Winslow Homer

+Peach+Blossoms.jpg) Winslow Homer (1836-1910) Peach Blossoms

Winslow Homer (1836-1910) Peach Blossoms+Girl+in+a+Garden.jpg) Winslow Homer (1836-1910) Girl in a Garden

Winslow Homer (1836-1910) Girl in a Garden+Peach+Blossoms+(2).jpg) Winslow Homer (1836-1910) Peach Blossoms

Winslow Homer (1836-1910) Peach Blossoms+Girls+with+Lobster.jpg) Winslow Homer (1836-1910) Girls with Lobster

Winslow Homer (1836-1910) Girls with Lobster+The+Garden+Wall.jpg) Winslow Homer (1836-1910) The Garden Wall

Winslow Homer (1836-1910) The Garden WallWinslow Homer (1836-1910) On the Fence

Sunday, June 14, 2020

19C Women & Gardens - American Frederick Childe Hassam 1859-1935

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Poppies on the Isles of Shoals, Maine.

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Celia Thaxter in Her Garden.

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Garden, Isles of Shoals, Maine.

.+In+the+Garden+at+Villers+le+Be+_1889.jpg) Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Reading in the Garden at Villers le Be 1889

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Reading in the Garden at Villers le Be 1889

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). After Breakfast. 1887

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Lilies. 1910

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Mrs Hassam in the Garden. 1896

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Reading. Date Unknown

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). In a French Garden. 1897

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). The Artist's Wife in a Garden Villiers le Bel. 1889

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Gathering Flowers in a French Garden. ca 1888

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Lady in the Park. 1897

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Woman Cutting Roses in a Garden. 1888-89

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). In the Garden. ca 1888-89

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Lady in Flower Garden. ca 1891

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935) Celia's Thaxter's Garden 1892

++Geraniums.jpg) Childe Hassam (1859-1935) Geraniums

Childe Hassam (1859-1935) Geraniums

++In+the+Park,+Paris.jpg) Childe Hassam (1859-1935) In the Park, Paris

Childe Hassam (1859-1935) In the Park, Paris

Childe Hassam (1859-1935) Listening to the Orchard Oriole

++Spring+the+Artist's+Sister.jpg) Childe Hassam (1859-1935) Spring the Artist's Sister

Childe Hassam (1859-1935) Spring the Artist's Sister

Childe Hassam (1859-1935) The Garden Door

+The+Fisherman's+Cottage.jpg) Childe Hassam (1859-1935) The Fisherman's Cottage

Childe Hassam (1859-1935) The Fisherman's Cottage

Childe Hassam (1859-1935) Mrs Hassam in the Garden 1888

Childe Hassam (1859-1935) Mrs Hassam at Villiers le Bel

Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Portrait of Edith Blaney with Garden behind Her, 1894. She is reading Celia Thaxter's An Island Garden, illustrated by Hassam, published in 1894.

Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Portrait of Edith Blaney with Garden behind Her, 1894. She is reading Celia Thaxter's An Island Garden, illustrated by Hassam, published in 1894.

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Garden

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). An Outdoor Portrait of Miss Weir, 1909

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). The Sea

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Celia Thaxter in Her Garden.

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Garden, Isles of Shoals, Maine.

.+In+the+Garden+at+Villers+le+Be+_1889.jpg) Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Reading in the Garden at Villers le Be 1889

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Reading in the Garden at Villers le Be 1889Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). After Breakfast. 1887

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Lilies. 1910

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Mrs Hassam in the Garden. 1896

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Reading. Date Unknown

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). In a French Garden. 1897

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). The Artist's Wife in a Garden Villiers le Bel. 1889

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Gathering Flowers in a French Garden. ca 1888

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Lady in the Park. 1897

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Woman Cutting Roses in a Garden. 1888-89

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). In the Garden. ca 1888-89

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Lady in Flower Garden. ca 1891

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935) Celia's Thaxter's Garden 1892

++Geraniums.jpg) Childe Hassam (1859-1935) Geraniums

Childe Hassam (1859-1935) Geraniums++In+the+Park,+Paris.jpg) Childe Hassam (1859-1935) In the Park, Paris

Childe Hassam (1859-1935) In the Park, ParisChilde Hassam (1859-1935) Listening to the Orchard Oriole

++Spring+the+Artist's+Sister.jpg) Childe Hassam (1859-1935) Spring the Artist's Sister

Childe Hassam (1859-1935) Spring the Artist's SisterChilde Hassam (1859-1935) The Garden Door

+The+Fisherman's+Cottage.jpg) Childe Hassam (1859-1935) The Fisherman's Cottage

Childe Hassam (1859-1935) The Fisherman's CottageChilde Hassam (1859-1935) Mrs Hassam in the Garden 1888

Childe Hassam (1859-1935) Mrs Hassam at Villiers le Bel

Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Portrait of Edith Blaney with Garden behind Her, 1894. She is reading Celia Thaxter's An Island Garden, illustrated by Hassam, published in 1894.

Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Portrait of Edith Blaney with Garden behind Her, 1894. She is reading Celia Thaxter's An Island Garden, illustrated by Hassam, published in 1894.Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Garden

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). An Outdoor Portrait of Miss Weir, 1909

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935). The Sea

Friday, June 12, 2020

19C Women & Gardens - American John Singer Sargent 1856-1925

+Florence+Fountain+Boboli+Gardens.jpg)

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) Florence Fountain Boboli Gardens

John Singer Sargent was not actually brought up in America. Sargent was born in Florence, Italy, and spent his childhood & adolescence touring Europe with his American parents who had decided on a nomadic lifestyle abroad in pursuit of culture rather than a more secure existence back home.

.++Villa+di+Marllia+Lucca.jpg) John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) Villa di Marllia Lucca

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) Villa di Marllia Lucca.++Villa+di+Marlia+Fountain.jpg) John Singer Sargent (1856-1925)Villa di Marlia Fountain

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925)Villa di Marlia FountainThe+Garden+Wall.jpg) John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) The Garden Wall

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) The Garden WallJohn Singer Sargent (1856-1925)Villa Torlonia Frascati

.++Garden+in+Corfu+1.jpg) John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) Garden in Corfu

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) Garden in Corfu.++Villa+Torre+Galli+The+Loggia.jpg) John Singer Sargent (1856-1925)Villa Torre Galli The Loggia

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925)Villa Torre Galli The Loggia+On+the+Veranda+at+Ironbound+Island,+Maine..jpg) John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) On the Garden Veranda at Ironbound Island, Maine.

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) On the Garden Veranda at Ironbound Island, Maine.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

+Flowers+along+the+White+Picket+Fence.jpg)

%2B%2BGirl%2Band%2BLaurel%2B(2).jpg)

.+CeliathaxtersGardenIslesofShoalsMaine.jpg)

.jpg)

.+Garden++(47).jpg)

.+After+Breakfast+1887.jpg)

.+Lilies+1910.jpg)

.+Mrs+Hassam+in+the+Garden+1896.jpg)

.+Reading+Unknown+(2).jpg)

.+In+a+French+Garden+1897.jpg)

.+The+Artist-s+Wife+in+a+Garden+Villiers+le+Bel+1889.jpg)

.+Gathering+Flowers+in+a+French+Garden+ca+1888.jpg)

.+Lady+in+the+Park+1897.jpg)

.+Woman+Cutting+Roses+in+a+Garden+1888-89.jpg)

.jpg)

.+Lady+in+Flower+Garden+ca+1891+(2).jpg)

.+Celia+Thaxter's+Isles+of+Shoals+Garden+(also+called+The+Garden+in+Its+Glory)+1892.jpg)

.+Garden++(30).jpg)

.++Garden++(32).jpg)

.+Garden++(51).jpg)

.+Garden++(50).jpg)

.+Garden++(62).jpg)

.++Garden++(35).jpg)

.++Garden++(69).jpg)