The British garden books that dominated the American market until the early 19th century, however inadequate & misleading their planting instructions, are valuable tools for reconstructing not only plant materials recommended but also methods used in designing & laying out 18th century gardens for both pleasure and food.

Catalogues of the circulating libraries that blossomed near the Atlantic after the Revolution are one important source in revealing gardening books used during this period. Other documents sometimes mentioning gardening books are letters, inventories, newspaper advertisements, diaries, and broadsides.

Some extant private book collections from the period remain in colonial libraries such as Thomas Jefferson's. Among the surviving libraries are those of the Ridgely family at Hampton in Baltimore County and the books of Charles Carroll the Barrister (1723-1783), housed at his home Mount Clare in Baltimore City.

An examination of the books read by colonial gardeners may help explain their tenacious refusal to let go of the formal garden concepts of the "ancients" -- like the geometric terraces found at both Hampton and Mount Clare--and accept the natural grounds revolution of their English contemporaries.

The surviving letters of 18th century Marylanders such as Henry Callister and Charles Carroll the Barrister often mention gardening books. Henry Callister (1716-1765) spent several years in a Liverpool counting house, before his employers sent him to oversee their store at Oxford on Maryland's Eastern Shore. Evidence of the frequent exchange of books among gardening readers on the Eastern Shore is found scattered throughout Callister's letterbooks.

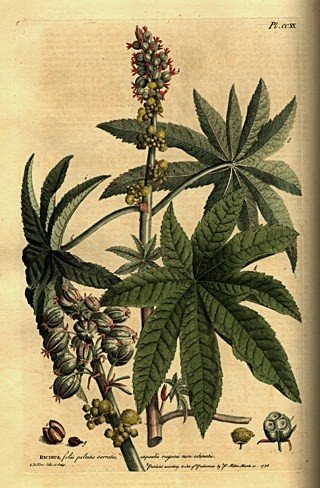

The Eastern Shore tobacco factor Callister owned the 2 volume collection of Figures of the most beautiful, useful, and uncommon plants described in the Gardeners Dictionary. It had been printed for the author; and sold by J. Rivington in London, from 1755-1760. The illustrator was Philip Miller (1691-1771), one of the most important English horticultural figures of the 18th century.

Philip Miller, Plate CCXX. Ricinus. from Figures of the most beautiful, useful, and uncommon plants described in the Gardeners Dictionary

Philip Miller, Plate CCXX. Ricinus. from Figures of the most beautiful, useful, and uncommon plants described in the Gardeners DictionaryAn acquaintance heard that Callister had the collection and knowing that Maryland's Governor Horatio Sharpe owned the Miller Gardener's Dictionary mentioned to him that Callister might sell the illustrations.

Callister wrote the Governor, offering him the watercolor plates for 15 pounds Maryland currency, which he declared was his actual cost, "Barclay favored me with the intimation of your Excellencies willingness to take off my hands Miller's Cuts. I have accordingly packed them up and deliver'd them to him. You will find inclosed an account of the nett prime cost. As your excellency is possessed of the Dictionary in folio, in which Mr. Millers Design was to adapt those cuts, they will be curious illustrations of his subject. But I have reason to think this was not his motive; your beneficence is seen in your laying hold of the occasion to ease me of a burthersome article' for the piece is indeed costly, and your taste seems to run rather on improvements in agriculture than mere entertainment in botany and natural history. For this I sincerely thank your Excellency."

The Governor did buy the books written and illustrated by Philip Miller, son of a Scotsman who served as a gardener in Kent before becoming a market gardener near Deptford.

Miller's Gardener's Dictionary was the backbone of most American garden libraries. It dealt with all aspects of gardening from kitchen gardens growing fruits, herbs, and vegetables to pleasure gardens. Virginians George Washington and Thomas Jefferson owned copies as did many other Chesapeake gentry. The complete title surveys the scope of the work: The gardeners dictionary: containing the methods of cultivating and improving the kitchen, fruit, and flower garden. As also, the physick garden, wilderness, conservatory and vineyard... Interspers'd with the history of the plants, the characters of each genus, and the names of all particular species, in Latin and English; and an explanation of all the terms used in botany and gardening, etc. It was first published in London in 1731 and revised in many editions over the coming years.

Even Benjamin Franklin, not known to be a gardener, wrote to his wife Deborah Franklin, 27 May 1757: "In my Room, on the Folio Shelf, between the Clock and our Bed Chamber, and not far from the Clock, stands a Folio call'd the Gardener's Dictionary, by P. Miller ... Deliver ... to Mr. (James) Parker"

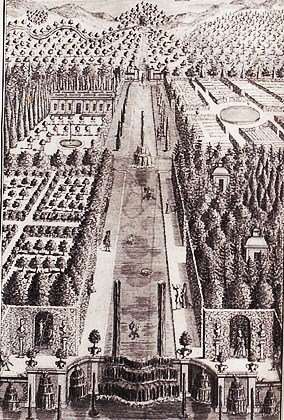

Frontis Piece from Philip Miller's Gardener's Dictionary. 1731

Frontis Piece from Philip Miller's Gardener's Dictionary. 1731A copy of Miller's Gardener's Dictionary still exists in the library at Mount Clare in Baltimore City, home of Charles Carroll the Barrister, son of Dr. Charles Carroll (1691-1755). Dr. Carroll came to the colony about 1715 to practice medicine. He became a planter, ship-builder, land speculator, and part-owner of a large iron business. Like many other Maryland planters, the elder Carroll ordered his books directly from England, where he sent his son Charles to be educated. Charles Carroll the Barrister returned to Maryland a few months before his father died. One of the first things the Barrister did after his father's death was to pay debts his father owed a London bookseller.

In 1760, as the son began to plan his new country house near Baltimore, he ordered a copy of Miller's Gardener's Dictionary. By 1766, Charles Carroll the Barrister was ordering his seeds from his British factors by noting specific seed types directly from the English gardening books on his shelves. The Barrister's letters referred to Miller's treatise frequently using it to describe varieties of peach and apricot trees he wished to plant in his garden. He wrote, "The Nursery Man may Look into Millars Gardeners Dictionary where he will See the Names of Each.".