Vick's Illustrated Floral Guide for 1873, issued quarterly, pp. 132.

This article was written by seed dealer James Vick (1818-1882) of Rochester, New York, in pages 21-24 of Vick's Illustrated Floral Guide for 1873.

Store Front Wood engraving from Vick's Illustrated Floral Guide for 1873

OUR SEED HOUSE

It is acknowledged that I have the largest and best regulated retail Seed House in the world. It is visited by thousands every year from all parts of this country, and by many from Europe, and 1 take pleasure in exhibiting everything of interest or profit to visitors. As hundreds of thousands of my customers will probably never have the opportunity of making a personal visit, I thought a few facts and illustrations would be interesting to this large class whom 1 am anxious to please, and be, at least, an acknowledgement of a debt of gratitude for long continued confidence, which I can feel, but not repay.

Inside the Store Wood engraving from Vick's Illustrated Floral Guide for 1873

Two Catalogues are issued each year, one of Bulbs in August, and on the first of December a beautiful Floral Guide:, of 130 pages, finely illustrated with hundreds of engravings of Flowers and plants and colored plates. Last year, the number printed was three hundred thousand at a cost of over sixty thousand dollars. In addition to the ordinary conveniences of a well regulated Seed House, there is connected with this establishment a Printing Office, Bindery, Box Making Establishment, and Artists’ and Engravers’ Rooms. Everything but the paper being made in the establishment.

Vick Store and Processing Center on State Street in Rochester, NY 1873 Wood engraving from Vick's Illustrated Floral Guide

To do this work fully occupies a building four stories in height (besides basement) sixty feet in width, and one hundred and fifty feet in length, with an addition in the upper story of a large room over an entire adjoining block.

BASEMENT

The large basement is arranged with immense quantities of drawers, &c., for storing Bulbs. Here, too, are stored the heavier kinds of Seeds, in sacks, &c., piled to the ceiling. The heavier packing is also done here.

FIRST FLOOR

The first floor is used entirely as a sales-shop, or “store,” for the sale of Seeds, Flowers, Plants and all Garden requisites and adornments, such as baskets, vases, lawn mowers, lawn tents, aquariums, seats, &c., &c. It is arranged with taste, and the songs of the birds, the fragrance and beauty of the flowers, make it a most delightful spot in which to spend an hour.

The Order Room Wood engraving from Vick's Illustrated Floral Guide for 1873

SECOND FLOOR

On the second floor is the Business and Private Offices, and also the Mail Room in which all letters are opened. The opening of letters occupies the entire time of two persons, and they perform the work with astonishing rapidity – practice making perfect – often opening three thousand in a day. After these letters are opened they are passed into what is called the Registering Room, on the same floor, where they are divided into States, and the name of the person ordering, and the date of the receipt of the order registered. They are then ready to be filled, and are passed into a large room, called the Order Room, where over seventy-five hands are employed, divided into gangs, each set, or gang, to a State, half-a-dozen or more being employed on each of the larger States. After the orders are filled, packed and directed, they are sent to what is known as the Post Office, also on the same floor, where the packages are weighed, the necessary stamps put upon them, and stamps cancelled, when they are packed in Post Office bags furnished us by Government, properly labeled for the different routes, and sent to the Postal Cars. Tons of Seeds are thus dispatched every day during the business season.

The Packing Room Wood engraving from Vick's Illustrated Floral Guide for 1873

THIRD FLOOR

Here is the German Department, where all orders written in the German language are filled by German clerks; a Catalogue in this language being published. On this floor, also, all seeds are packed, that is, weighed and measured and placed in paper bags and stored ready for sale. About fifty persons are employed in this room, surrounded by thousands of nicely labeled drawers.

FOURTH FLOOR

On this floor are rooms for Artists and Engravers, several of whom are kept constantly employed in designing and engraving for Catalogues and Chromos. Here, also, the lighter seed are stored. In a large room adjoining, is the Printing Office, where the Catalogue is prepared, and other printing done, and also the Bindery, often employing forty or fifty hands, and turning out more than ten thousand Catalogues in a day. Here is in use the most improved machinery for covering, trimming, &c., propelled by steam.

The Bindery Wood engraving from Vick's Illustrated Floral Guide for 1873

MISCELLANEOUS

The immense amount of business done may be understood by a few facts: Nearly one hundred acres are employed, near the city, in growing flower seeds mainly, while large importations are made from Germany, France, Holland, Australia and Japan. Over three thousand reams of printing paper are used each year for Catalogues, weighing two hundred thousand pounds, and the simple postage for sending these Catalogues by mail is thirteen thousand dollars. Over fifty thousand dollars have been paid the Government for postage stamps last year. Millions of bags and boxes are also manufactured in the establishment, requiring hundreds of reams of paper, and scores of tons of paste-board. The business is so arranged that the wrappers are prepared for each State, with the name of the State conspicuously printed, thus saving a great deal of writing. as well as preventing errors.

I had prepared several other engravings of German Room, Printing Office, Artists’ Room, Counting Room, Mail Room, Post Office, &c., but have already occupied quite enough space give readers somewhat of an idea of the character of my establishment. Another year, I may give further particulars. James Vick

Seedsman James Vick (1818-1882)

James Vick was one of the merchants who dominated the floral nursery industry in New York in the 19C. James Vick was born in Portsmouth, England on Nov. 23, 1818. In 1833, at the age of 12, he arrived in New York City to learn the printing trade. By the time he moved to Rochester, he had acquired skills as a printer & writer.

In 1837, he moved with his parents to Rochester, New York, where he set type for several newspapers & journals. In 1849, James Vick was elected corresponding secretary of the Genesee Valley Horticultural Society. From 1849 through the early 1850s, Vick edited & then bought the popular journal The Genesee Farmer in 1855. He later owned part of a workers’ journal and helped to found Frederick Douglass’s North Star.

Vick’s house in 1871

With Vick as editor, the publication became more elegant & circulation rapidly increased. A year later he sold out to Joseph Harris. On the death of A. J. Downing, James Vick bought "The Horticulturist" & moved it to Rochester in 1853. For for 3 years he published this with Patrick Barry serving as Editor. It was devoted to horticulture, floriculture, landscape gardening, & rural architecture.

About this time, Vick started to grow flowers & began sending seeds out by mail to the readers of his publication. Vick also started importing seed stock. In 1855, he established a seed store & printing house in Rochester for his growing mail order business. In 1856, Vick started "Rural Annual and Horticultural Directory". The first half was a seed catalog & the second a list of nurserymen. This was taken over in 1857 by Joseph Harris who continued it until 1867.

Vick's Home on the South Side of East Avenue in Rochester, NY. 1877

With Vick’s knowledge of chromolithography & printing, he produce a catalog & later a monthly magazine. The first, "Floral Guide and Catalogue" was printed in 1862. His "Floral Guides" provided gardening advice, quality color prints, & reached a circulation of 250,000. He entertained his readers with anecdotes, published letters he had received, & had a special section for children.

By the 1870s, as many as 150,000 catalogs were sent out each year. A staff of more than 100 worked in the office & packing house. There were over 75 acres of seed gardens scattered about the city. In 1878, Vick started a paper, "Vick’s Illustrated Monthly" which was published by the Vick Seed Company in Rochester & in Dansville until 1909. This magazine was sold by subscription. Vick also printed a set of chromolithograph prints which were either sold or offered as premiums with large orders.

The Seed House of James Vick 1881 From Commerce, Manufactures & Resources of Rochester, NY

Vick was one of the most successful American horticultural seedsman, writers, & merchandisers of his day. The Vick Seed Company continued into the 20C before being sold to the Burpee Seed Co.

Thanks to the Smithsonian Libraries Biographies of American Seedsmen & Nurserymen

Thursday, January 24, 2019

Wednesday, January 23, 2019

Plants in Early American Gardens - Sage

Sage (Salvia officinalis)

Sage was a standard in kitchen gardens from colonial times, and Thomas Jefferson listed it for the Monticello garden in 1794. This culinary Mediterranean shrub, grown since the 13th century, was thought to prolong life. Its soft, gray-green foliage and spikes of lavender flowers, beloved by pollinators, make it an attractive ornamental. Deer resistant.

Contact The Thomas Jefferson Center for Historic Plants at

Email chp@monticello.org

Phone 434-984-9819

Monday, January 21, 2019

Plants in Early American Gardens - Blue-podded Capucijner Pea

Blue-podded Capucijner Pea (Pisum sativum cv.)

The Blue-podded Capucijner (cap-ou-SIGH-nah) is a hardy pea first grown by the Franciscan Capuchin monks in Holland and Germany during the early 1600s. Its particularly beautiful, bi-colored flowers are lilac-pink and wine-red, fading to blue as they wilt; pods are deep maroon to inky purple, fading to blue and leathery brown when mature. It is best used as a soup pea by picking when the pods are full; but it can also be grown as an edible-podded sugar pea by harvesting before peas have developed.

Contact The Thomas Jefferson Center for Historic Plants at

Email chp@monticello.org

Phone 434-984-9819

Sunday, January 20, 2019

Gardening Books in Early America - Exchanging Garden Books

Many gentlemen gardeners ordered their design & planting instruction books, as well as seeds, plants, and even their gardeners from England. Despite wide discrepancies in both soil & climate among the colonies themselves and certainly between these "new" lands & mother England, gardeners up & down the Atlantic depended on English garden publications until well after the Revolution.

The British garden books that dominated the American market until the early 19th century, however inadequate & misleading their planting instructions, are valuable tools for reconstructing not only plant materials recommended but also methods used in designing & laying out 18th century gardens for both pleasure and food.

Catalogues of the circulating libraries that blossomed near the Atlantic after the Revolution are one important source in revealing gardening books used during this period. Other documents sometimes mentioning gardening books are letters, inventories, newspaper advertisements, diaries, and broadsides.

Some extant private book collections from the period remain in colonial libraries such as Thomas Jefferson's. Among the surviving libraries are those of the Ridgely family at Hampton in Baltimore County and the books of Charles Carroll the Barrister (1723-1783), housed at his home Mount Clare in Baltimore City.

An examination of the books read by colonial gardeners may help explain their tenacious refusal to let go of the formal garden concepts of the "ancients" -- like the geometric terraces found at both Hampton and Mount Clare--and accept the natural grounds revolution of their English contemporaries.

The surviving letters of 18th century Marylanders such as Henry Callister and Charles Carroll the Barrister often mention gardening books. Henry Callister (1716-1765) spent several years in a Liverpool counting house, before his employers sent him to oversee their store at Oxford on Maryland's Eastern Shore. Evidence of the frequent exchange of books among gardening readers on the Eastern Shore is found scattered throughout Callister's letterbooks.

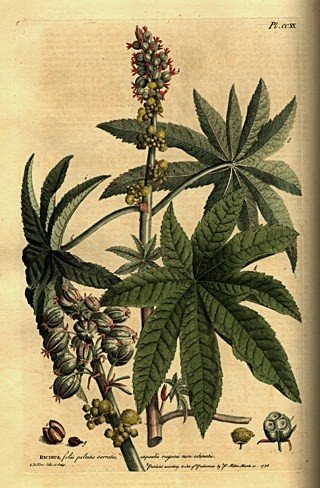

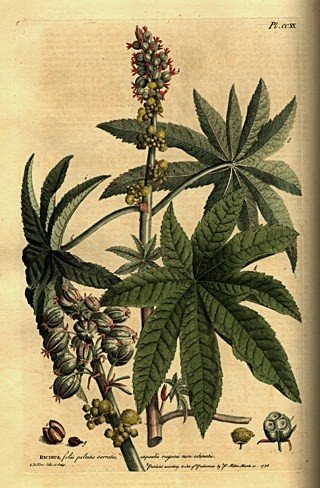

The Eastern Shore tobacco factor Callister owned the 2 volume collection of Figures of the most beautiful, useful, and uncommon plants described in the Gardeners Dictionary. It had been printed for the author; and sold by J. Rivington in London, from 1755-1760. The illustrator was Philip Miller (1691-1771), one of the most important English horticultural figures of the 18th century.

Philip Miller, Plate CCXX. Ricinus. from Figures of the most beautiful, useful, and uncommon plants described in the Gardeners Dictionary

Philip Miller, Plate CCXX. Ricinus. from Figures of the most beautiful, useful, and uncommon plants described in the Gardeners Dictionary

An acquaintance heard that Callister had the collection and knowing that Maryland's Governor Horatio Sharpe owned the Miller Gardener's Dictionary mentioned to him that Callister might sell the illustrations.

Callister wrote the Governor, offering him the watercolor plates for 15 pounds Maryland currency, which he declared was his actual cost, "Barclay favored me with the intimation of your Excellencies willingness to take off my hands Miller's Cuts. I have accordingly packed them up and deliver'd them to him. You will find inclosed an account of the nett prime cost. As your excellency is possessed of the Dictionary in folio, in which Mr. Millers Design was to adapt those cuts, they will be curious illustrations of his subject. But I have reason to think this was not his motive; your beneficence is seen in your laying hold of the occasion to ease me of a burthersome article' for the piece is indeed costly, and your taste seems to run rather on improvements in agriculture than mere entertainment in botany and natural history. For this I sincerely thank your Excellency."

The Governor did buy the books written and illustrated by Philip Miller, son of a Scotsman who served as a gardener in Kent before becoming a market gardener near Deptford.

Miller's Gardener's Dictionary was the backbone of most American garden libraries. It dealt with all aspects of gardening from kitchen gardens growing fruits, herbs, and vegetables to pleasure gardens. Virginians George Washington and Thomas Jefferson owned copies as did many other Chesapeake gentry. The complete title surveys the scope of the work: The gardeners dictionary: containing the methods of cultivating and improving the kitchen, fruit, and flower garden. As also, the physick garden, wilderness, conservatory and vineyard... Interspers'd with the history of the plants, the characters of each genus, and the names of all particular species, in Latin and English; and an explanation of all the terms used in botany and gardening, etc. It was first published in London in 1731 and revised in many editions over the coming years.

Even Benjamin Franklin, not known to be a gardener, wrote to his wife Deborah Franklin, 27 May 1757: "In my Room, on the Folio Shelf, between the Clock and our Bed Chamber, and not far from the Clock, stands a Folio call'd the Gardener's Dictionary, by P. Miller ... Deliver ... to Mr. (James) Parker"

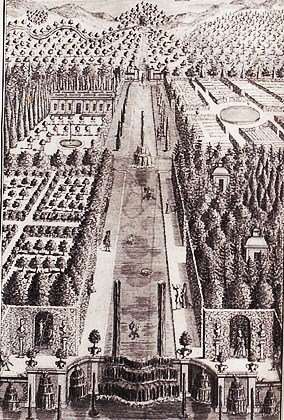

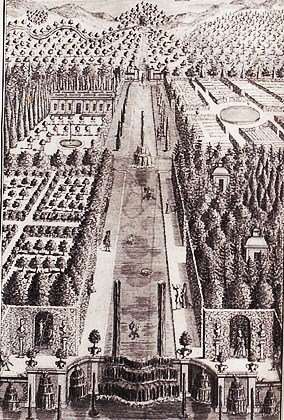

Frontis Piece from Philip Miller's Gardener's Dictionary. 1731

Frontis Piece from Philip Miller's Gardener's Dictionary. 1731

A copy of Miller's Gardener's Dictionary still exists in the library at Mount Clare in Baltimore City, home of Charles Carroll the Barrister, son of Dr. Charles Carroll (1691-1755). Dr. Carroll came to the colony about 1715 to practice medicine. He became a planter, ship-builder, land speculator, and part-owner of a large iron business. Like many other Maryland planters, the elder Carroll ordered his books directly from England, where he sent his son Charles to be educated. Charles Carroll the Barrister returned to Maryland a few months before his father died. One of the first things the Barrister did after his father's death was to pay debts his father owed a London bookseller.

In 1760, as the son began to plan his new country house near Baltimore, he ordered a copy of Miller's Gardener's Dictionary. By 1766, Charles Carroll the Barrister was ordering his seeds from his British factors by noting specific seed types directly from the English gardening books on his shelves. The Barrister's letters referred to Miller's treatise frequently using it to describe varieties of peach and apricot trees he wished to plant in his garden. He wrote, "The Nursery Man may Look into Millars Gardeners Dictionary where he will See the Names of Each.".

The British garden books that dominated the American market until the early 19th century, however inadequate & misleading their planting instructions, are valuable tools for reconstructing not only plant materials recommended but also methods used in designing & laying out 18th century gardens for both pleasure and food.

Catalogues of the circulating libraries that blossomed near the Atlantic after the Revolution are one important source in revealing gardening books used during this period. Other documents sometimes mentioning gardening books are letters, inventories, newspaper advertisements, diaries, and broadsides.

Some extant private book collections from the period remain in colonial libraries such as Thomas Jefferson's. Among the surviving libraries are those of the Ridgely family at Hampton in Baltimore County and the books of Charles Carroll the Barrister (1723-1783), housed at his home Mount Clare in Baltimore City.

An examination of the books read by colonial gardeners may help explain their tenacious refusal to let go of the formal garden concepts of the "ancients" -- like the geometric terraces found at both Hampton and Mount Clare--and accept the natural grounds revolution of their English contemporaries.

The surviving letters of 18th century Marylanders such as Henry Callister and Charles Carroll the Barrister often mention gardening books. Henry Callister (1716-1765) spent several years in a Liverpool counting house, before his employers sent him to oversee their store at Oxford on Maryland's Eastern Shore. Evidence of the frequent exchange of books among gardening readers on the Eastern Shore is found scattered throughout Callister's letterbooks.

The Eastern Shore tobacco factor Callister owned the 2 volume collection of Figures of the most beautiful, useful, and uncommon plants described in the Gardeners Dictionary. It had been printed for the author; and sold by J. Rivington in London, from 1755-1760. The illustrator was Philip Miller (1691-1771), one of the most important English horticultural figures of the 18th century.

Philip Miller, Plate CCXX. Ricinus. from Figures of the most beautiful, useful, and uncommon plants described in the Gardeners Dictionary

Philip Miller, Plate CCXX. Ricinus. from Figures of the most beautiful, useful, and uncommon plants described in the Gardeners DictionaryAn acquaintance heard that Callister had the collection and knowing that Maryland's Governor Horatio Sharpe owned the Miller Gardener's Dictionary mentioned to him that Callister might sell the illustrations.

Callister wrote the Governor, offering him the watercolor plates for 15 pounds Maryland currency, which he declared was his actual cost, "Barclay favored me with the intimation of your Excellencies willingness to take off my hands Miller's Cuts. I have accordingly packed them up and deliver'd them to him. You will find inclosed an account of the nett prime cost. As your excellency is possessed of the Dictionary in folio, in which Mr. Millers Design was to adapt those cuts, they will be curious illustrations of his subject. But I have reason to think this was not his motive; your beneficence is seen in your laying hold of the occasion to ease me of a burthersome article' for the piece is indeed costly, and your taste seems to run rather on improvements in agriculture than mere entertainment in botany and natural history. For this I sincerely thank your Excellency."

The Governor did buy the books written and illustrated by Philip Miller, son of a Scotsman who served as a gardener in Kent before becoming a market gardener near Deptford.

Miller's Gardener's Dictionary was the backbone of most American garden libraries. It dealt with all aspects of gardening from kitchen gardens growing fruits, herbs, and vegetables to pleasure gardens. Virginians George Washington and Thomas Jefferson owned copies as did many other Chesapeake gentry. The complete title surveys the scope of the work: The gardeners dictionary: containing the methods of cultivating and improving the kitchen, fruit, and flower garden. As also, the physick garden, wilderness, conservatory and vineyard... Interspers'd with the history of the plants, the characters of each genus, and the names of all particular species, in Latin and English; and an explanation of all the terms used in botany and gardening, etc. It was first published in London in 1731 and revised in many editions over the coming years.

Even Benjamin Franklin, not known to be a gardener, wrote to his wife Deborah Franklin, 27 May 1757: "In my Room, on the Folio Shelf, between the Clock and our Bed Chamber, and not far from the Clock, stands a Folio call'd the Gardener's Dictionary, by P. Miller ... Deliver ... to Mr. (James) Parker"

Frontis Piece from Philip Miller's Gardener's Dictionary. 1731

Frontis Piece from Philip Miller's Gardener's Dictionary. 1731A copy of Miller's Gardener's Dictionary still exists in the library at Mount Clare in Baltimore City, home of Charles Carroll the Barrister, son of Dr. Charles Carroll (1691-1755). Dr. Carroll came to the colony about 1715 to practice medicine. He became a planter, ship-builder, land speculator, and part-owner of a large iron business. Like many other Maryland planters, the elder Carroll ordered his books directly from England, where he sent his son Charles to be educated. Charles Carroll the Barrister returned to Maryland a few months before his father died. One of the first things the Barrister did after his father's death was to pay debts his father owed a London bookseller.

In 1760, as the son began to plan his new country house near Baltimore, he ordered a copy of Miller's Gardener's Dictionary. By 1766, Charles Carroll the Barrister was ordering his seeds from his British factors by noting specific seed types directly from the English gardening books on his shelves. The Barrister's letters referred to Miller's treatise frequently using it to describe varieties of peach and apricot trees he wished to plant in his garden. He wrote, "The Nursery Man may Look into Millars Gardeners Dictionary where he will See the Names of Each.".

Saturday, January 19, 2019

Plants in Early American Gardens - Mammoth Sandwich Island Salsify

Mammoth Sandwich Island Salsify (Tragopogon porrifolius cv.)

Salsify has been cultivated in Europe for its edible, carrot-like root since the 16th century. Jefferson planted “Salsafia” as early as 1774 in his Monticello vegetable garden, and called it "one of the best roots for winter" in 1812. Mammoth Sandwich Island Salsify is a biennial, purple-flowering variety first distributed in New York in the late 1880s and was promoted for its high yield.

Contact The Thomas Jefferson Center for Historic Plants at

Email chp@monticello.org

Phone 434-984-9819

Salsify has been cultivated in Europe for its edible, carrot-like root since the 16th century. Jefferson planted “Salsafia” as early as 1774 in his Monticello vegetable garden, and called it "one of the best roots for winter" in 1812. Mammoth Sandwich Island Salsify is a biennial, purple-flowering variety first distributed in New York in the late 1880s and was promoted for its high yield.

Contact The Thomas Jefferson Center for Historic Plants at

Email chp@monticello.org

Phone 434-984-9819

Friday, January 18, 2019

Gardening Books in Early America - Overview

Practical farming & gardening books far outnumbered books devoted exclusively to pleasure gardening on the bookshelves of colonial & early American gardeners. Agriculture was the main source of income for most colonial families. Once a landowner was producing enough off of his land to support his family, he might have the time & the extra funds to begin to transform some of his land, closest to his house, into a pleasure garden. It was his art.

Often the necessary agricultural instruction books contained information on gardening as well. We can learn which farming books were in use in the colonies from death inventories. Marylanders were fairly faithful inventory recorders. Although scattered estate inventory records dating back to 1674, do exist in the state, these documents are nearly complete after a 1715 law required all executors to make an estate inventory within 3 months of death.

Unfortunately inventory takers were not often very specific when recording book titles & seldom listed authors, so the interpretation of precisely what book was recorded in early property lists is difficult. The 1718 inventory of William Bladen, who was Secretary of Maryland in 1701, & Attorney General in 1707, listed John Evelyn's (1620-1706) The Complete Gardener published in London in 1693. It was a translation of a French work by Jean de la Quintinie (1629-1688). The "Art of Gardening" which appears in several early inventories was probably the work of the English author, Leonard Meager. His book, actually titled The New Art of Gardening, was published in London in 1697.

The extant letters of 18th century Marylanders Henry Callister & Charles Carroll the Barrister (of Mount Clare) often mention farming books. Henry Callister (1716-1765) spent several years in a Liverpool counting house, before his employers sent him to manage their store at Oxford on Maryland's Eastern Shore. Evidence of the frequent exchange of books among gardening readers on the Eastern Shore is found scattered throughout his letterbooks.

After his arrival in Maryland, Callister became acquainted with a prosperous planter William Carmichael, who lived near Chestertown. Callister borrowed Carmichael's copy of Jethro Tull's (1647-1741) Horse-Hoeing Husbandry: Or, an Essay on the Principals of Tillage and Vegetation published in 1733. The book was a classic, and Tull came to be called the "father of modern husbandry." Callister also owned a copy of Joseph Pitton de Tournefort's (1656-1708) History of Plants Growing about Paris, With Their Use in Physick, and a mechanical account of the operation of medicines. Translated into English, with many additions, & accommodated to the plants growing in Great Britain by John Martyn, it was published by C. Riverington in London in 1732.

Callister offered to sell this particular book to a fellow gardener in 1765, "I have a small posthumous work of Tournefort...it gives the description & use of plants in medicine, with their chymical analysis; it is an 2v. 12 degree worth 12/6 Currency. I shall send it if you like. I would now, as it might be return'd if not wanted, but there are a few things in it which I would read first."

The book's author Joseph Pitton de Tournefort became professor of Botany at the Jardin du Roi botanic garden in Paris in 1683, and later made various expeditions in Europe & the Near East in search of plants. In 1688, he took his degree of Doctor of Medicine at the University of Orange. The book's English translator, John Martyn (1699-1768) was Professor of Botany at Cambridge from 1732 until 1762.

By 1766, Charles Carroll the Barrister was ordering his seeds for Mount Clare from his British factors by noting specific seed types directly from the English gardening books on his shelves. That year he copied a long list of seeds "from Hale's Complete Body of Husbandry," first published in London in 1755/56, asking his English agents to send as many of them as possible to Maryland.

Another book referred to by the Barrister was Thomas Hale's Eden: or a compleat body of gardening...(or ratehr by Sir. J. Hill) published in London in 1756-57. John Hill (1716-1775) was the son of a Lincolnshire clergyman brought up to be an apothecary. During his apprenticeship he attended the lectures on botany of the Chelsea botanic garden. In 1750, he was granted a degree as a Doctor of Medicine from the University of St. Andrews. In 1760, he assisted in laying out a botanic garden at Kew & was a gardener at Kensington Palace. Carroll's copy of Hale's Complete Husbandry still exists in the library at Mount Clare.

The Barrister was also interested in the agricultural reforms sweeping England. He not only knew which specific books he wanted his English agents to buy but was able to direct them to the specific publishing houses in London that stocked the desired works. He ordered, "A new and Complete System of Practical Husbandry by John Mills Esquire, Editor of Duhamels Husbandry printed by John Johnson at the monument... Essays on Husbandry Essay the first On The Ancient and Present State of Agriculture and the Second On Lucern Printed for William Frederick at Bath 1764. Sold by Hunter at Newgate Street or Johnston in Ludgate Street."

The Barrister's distant cousin who signed the Declaration of Independence, Charles Carroll of Carrollton (1737-1832), also ordered farming & gardening books from England. By the mid 1760s, his family's library in Annapolis contained Miller's Dictionary & Richard Bradley's (1686-1732) New Improvement of Planting and Gardening published in London in 1726. Bradley's work appeared in several Maryland inventories in the 1730's. Bradley studied gardening in France and Holland; and in 1724, he was appointed the first professor of Botany at Cambridge.

Another popular English publication in Carroll's library by the mid-1760s was Batty Langley's (1696-1751) New Principles of Gardening... with Experimental Directions for Raising several kinds of Fruit Trees, Forest Trees, Evergreens and Flowering Shrubs. Later the Carrolls added to their library Richard Weston's (1733-1806) Gardener's and Planter's Calendar published in Dublin in 1782. Weston was a thread hosier in Leicester who had travelled in France & Holland as Secretary of the Leicester Agricultural Society.

The letters of Henry Callister & the several Maryland Carrolls show that many of the books owned by Marylanders were imported directly from London in exchange for the annual tobacco shipment or goods such as iron ore. Before the Revolution wealthy planters & merchants depended on their own private libraries often exchanging books with one another. When literate farmers & planters died, their books were passed to others with deliberate care. At the death of Virginian gentleman William Ludlow in the mid 1760s, his books were offered for sale directly to Charles Carroll of Carrollton who chose two gardening books from the Virginian's collection including Batty Langley's treatise.

Direct trade with London booksellers gradually decreased, as tobacco became less important in the economic life of Maryland and as trade was curtailed during the Revolution. As a result, bookstores & circulating libraries began to appear in Annapolis & Baltimore. Their appearance coincided with the rise of a literate merchant class. Before the Revolution, there were a few booksellers in colonial Maryland. William Aikman was an early bookseller in Annapolis who imported quantities of books from London for sale directly to colonial readers. In the Maryland Gazette of June 23, 1774, he advertised for sale "Adam Dickson, A Treatise on Agriculture...2 vol. Edinburgh, 1770."

Several Maryland booksellers quickly realized that not all readers in the new nation could afford to buy books for their personal use & started offering less costly circulating library services to expand their businesses. By 1783, Annapolis had its own circulating library offering a few farming & gardening books to subscribers. These included Richard Weston's Gardener's and Planter's Calendar (published only a year earlier in Ireland) and Thomas Mawe's Everyman His Own Gardener published in London by W. Griffin in 1767. Mawe was the gardener to the Duke of Leeds who only lent his name to give an air of authenticity to the publication actually written by John Abercrombie (1726-1806).

The largest collection of 18th century gardening & agricultural books owned in Maryland is referred to in earliest catalogue of the Library Company of Baltimore. These books formed the nucleus of information for Baltimore farmers for many years. In the December 1780 Maryland Journal, William Prichard advertised that he was opening a bookstore & establishing a circulating library of 1000 volumes in Baltimore. By 1784, a 2nd literary entrepreneur William Murphy opened a circulating library in the city, but the most information remains about the Library Company of Baltimore, which had 60 subscribers & 1300 volumes when it was chartered in 1796. By 1809 when the first catalogue was prepared, the library had over 400 members & 7000 volumes. By the next year there were about 35,000 people living in Baltimore, many visiting the Library Company to borrow an English or classical book on gardening.

Often the necessary agricultural instruction books contained information on gardening as well. We can learn which farming books were in use in the colonies from death inventories. Marylanders were fairly faithful inventory recorders. Although scattered estate inventory records dating back to 1674, do exist in the state, these documents are nearly complete after a 1715 law required all executors to make an estate inventory within 3 months of death.

Unfortunately inventory takers were not often very specific when recording book titles & seldom listed authors, so the interpretation of precisely what book was recorded in early property lists is difficult. The 1718 inventory of William Bladen, who was Secretary of Maryland in 1701, & Attorney General in 1707, listed John Evelyn's (1620-1706) The Complete Gardener published in London in 1693. It was a translation of a French work by Jean de la Quintinie (1629-1688). The "Art of Gardening" which appears in several early inventories was probably the work of the English author, Leonard Meager. His book, actually titled The New Art of Gardening, was published in London in 1697.

The extant letters of 18th century Marylanders Henry Callister & Charles Carroll the Barrister (of Mount Clare) often mention farming books. Henry Callister (1716-1765) spent several years in a Liverpool counting house, before his employers sent him to manage their store at Oxford on Maryland's Eastern Shore. Evidence of the frequent exchange of books among gardening readers on the Eastern Shore is found scattered throughout his letterbooks.

After his arrival in Maryland, Callister became acquainted with a prosperous planter William Carmichael, who lived near Chestertown. Callister borrowed Carmichael's copy of Jethro Tull's (1647-1741) Horse-Hoeing Husbandry: Or, an Essay on the Principals of Tillage and Vegetation published in 1733. The book was a classic, and Tull came to be called the "father of modern husbandry." Callister also owned a copy of Joseph Pitton de Tournefort's (1656-1708) History of Plants Growing about Paris, With Their Use in Physick, and a mechanical account of the operation of medicines. Translated into English, with many additions, & accommodated to the plants growing in Great Britain by John Martyn, it was published by C. Riverington in London in 1732.

Callister offered to sell this particular book to a fellow gardener in 1765, "I have a small posthumous work of Tournefort...it gives the description & use of plants in medicine, with their chymical analysis; it is an 2v. 12 degree worth 12/6 Currency. I shall send it if you like. I would now, as it might be return'd if not wanted, but there are a few things in it which I would read first."

The book's author Joseph Pitton de Tournefort became professor of Botany at the Jardin du Roi botanic garden in Paris in 1683, and later made various expeditions in Europe & the Near East in search of plants. In 1688, he took his degree of Doctor of Medicine at the University of Orange. The book's English translator, John Martyn (1699-1768) was Professor of Botany at Cambridge from 1732 until 1762.

By 1766, Charles Carroll the Barrister was ordering his seeds for Mount Clare from his British factors by noting specific seed types directly from the English gardening books on his shelves. That year he copied a long list of seeds "from Hale's Complete Body of Husbandry," first published in London in 1755/56, asking his English agents to send as many of them as possible to Maryland.

Another book referred to by the Barrister was Thomas Hale's Eden: or a compleat body of gardening...(or ratehr by Sir. J. Hill) published in London in 1756-57. John Hill (1716-1775) was the son of a Lincolnshire clergyman brought up to be an apothecary. During his apprenticeship he attended the lectures on botany of the Chelsea botanic garden. In 1750, he was granted a degree as a Doctor of Medicine from the University of St. Andrews. In 1760, he assisted in laying out a botanic garden at Kew & was a gardener at Kensington Palace. Carroll's copy of Hale's Complete Husbandry still exists in the library at Mount Clare.

The Barrister was also interested in the agricultural reforms sweeping England. He not only knew which specific books he wanted his English agents to buy but was able to direct them to the specific publishing houses in London that stocked the desired works. He ordered, "A new and Complete System of Practical Husbandry by John Mills Esquire, Editor of Duhamels Husbandry printed by John Johnson at the monument... Essays on Husbandry Essay the first On The Ancient and Present State of Agriculture and the Second On Lucern Printed for William Frederick at Bath 1764. Sold by Hunter at Newgate Street or Johnston in Ludgate Street."

The Barrister's distant cousin who signed the Declaration of Independence, Charles Carroll of Carrollton (1737-1832), also ordered farming & gardening books from England. By the mid 1760s, his family's library in Annapolis contained Miller's Dictionary & Richard Bradley's (1686-1732) New Improvement of Planting and Gardening published in London in 1726. Bradley's work appeared in several Maryland inventories in the 1730's. Bradley studied gardening in France and Holland; and in 1724, he was appointed the first professor of Botany at Cambridge.

Another popular English publication in Carroll's library by the mid-1760s was Batty Langley's (1696-1751) New Principles of Gardening... with Experimental Directions for Raising several kinds of Fruit Trees, Forest Trees, Evergreens and Flowering Shrubs. Later the Carrolls added to their library Richard Weston's (1733-1806) Gardener's and Planter's Calendar published in Dublin in 1782. Weston was a thread hosier in Leicester who had travelled in France & Holland as Secretary of the Leicester Agricultural Society.

The letters of Henry Callister & the several Maryland Carrolls show that many of the books owned by Marylanders were imported directly from London in exchange for the annual tobacco shipment or goods such as iron ore. Before the Revolution wealthy planters & merchants depended on their own private libraries often exchanging books with one another. When literate farmers & planters died, their books were passed to others with deliberate care. At the death of Virginian gentleman William Ludlow in the mid 1760s, his books were offered for sale directly to Charles Carroll of Carrollton who chose two gardening books from the Virginian's collection including Batty Langley's treatise.

Direct trade with London booksellers gradually decreased, as tobacco became less important in the economic life of Maryland and as trade was curtailed during the Revolution. As a result, bookstores & circulating libraries began to appear in Annapolis & Baltimore. Their appearance coincided with the rise of a literate merchant class. Before the Revolution, there were a few booksellers in colonial Maryland. William Aikman was an early bookseller in Annapolis who imported quantities of books from London for sale directly to colonial readers. In the Maryland Gazette of June 23, 1774, he advertised for sale "Adam Dickson, A Treatise on Agriculture...2 vol. Edinburgh, 1770."

Several Maryland booksellers quickly realized that not all readers in the new nation could afford to buy books for their personal use & started offering less costly circulating library services to expand their businesses. By 1783, Annapolis had its own circulating library offering a few farming & gardening books to subscribers. These included Richard Weston's Gardener's and Planter's Calendar (published only a year earlier in Ireland) and Thomas Mawe's Everyman His Own Gardener published in London by W. Griffin in 1767. Mawe was the gardener to the Duke of Leeds who only lent his name to give an air of authenticity to the publication actually written by John Abercrombie (1726-1806).

The largest collection of 18th century gardening & agricultural books owned in Maryland is referred to in earliest catalogue of the Library Company of Baltimore. These books formed the nucleus of information for Baltimore farmers for many years. In the December 1780 Maryland Journal, William Prichard advertised that he was opening a bookstore & establishing a circulating library of 1000 volumes in Baltimore. By 1784, a 2nd literary entrepreneur William Murphy opened a circulating library in the city, but the most information remains about the Library Company of Baltimore, which had 60 subscribers & 1300 volumes when it was chartered in 1796. By 1809 when the first catalogue was prepared, the library had over 400 members & 7000 volumes. By the next year there were about 35,000 people living in Baltimore, many visiting the Library Company to borrow an English or classical book on gardening.

Thursday, January 17, 2019

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)