When Ben Franklin wrote, "Beer is living proof that God loves us and wants us to be happy," he was speaking for many Americans of his day. Beer, and the art of brewing, was one of the first things European settlers needed America in the 17th century.

The Mayflower landed on Plymouth Rock in the winter of 1620. They’d actually landed on Cape Cod in November & tried to sail south to their intended destination—The Virginia Colony, still 220 miles south—eventually ending up in Plymouth Rock. The choice to land was due in part to treacherous shoals & breakers facing Mayflower Captain Christopher Jones off the cold coast of Cape Cod—but it was also due in large part to a dangerous shortage of beer.

When he became alarmed that his ship's supply of beer was running low, Captain Jones decided to land at Plymouth Rock (rather than sailing further south) to "winter" there. It was determined that the passengers & servants should go ashore to seek out new water (hopefully to make more beer). Captain Jones sent all passengers off the ship into the frigid New England winter on December 19th, 1620.

The ship's crew remained on the moored vessel, reserving the beer for themselves. One passenger, William Bradford, complained that he & other passengers "were hastened ashore & made to drink water, that the seamen might have the more beer." And even though the pilgrims discovered clean streams ashore, they were suspicious of the New World liquid & not altogether fond of its taste. As one colonist was quick to write, "I dare not prefere it before good beere"

To the Pilgrims on the Mayflower, beer had become an essential part of daily life. Even the children drank beer. "Ship's beer" as it was known, did not have high alcohol content. Neither did the even weaker "small beer," of which passengers drank a quart per day. Beer was stored on board many seagoing ships; because after being stored for long periods of time, a ship's water would become a contaminated, germy affair. Beer, on the other hand, could be stored & ingested for weeks & months without ill effect, making it the ideal beverage for a lengthy journey — as long as there was enough to go around.

At Plymouth Rock, the Wampanoags reportedly taught them how to ferment alcohol, but not beer. Along the Atlantic coast, hops were scarce. Some settlers did manage to find hops growing in the wild, but their supply was quickly exhausted, leaving them in the same awful situation they were in, when they were dropped off by the sailors here in the first place.

In Jamestown, Virginia, the situation was even worse. Somehow, the Virginia Company had sent the early settlers to the colony without thinking to bring someone who actually knew how to make beer. The settlers planted a field of barley, put an ad in a 1609 London paper asking for two brewers to sail over; and later in 1609, they finally brewed beer. The remnants of the very first “brewery” in America can be seen at Historic Jamestowne.

The early colonist's desire for beer was both a born-in cultural habit as well as what was then a common-sense approach not to drink strange water and possibly die in any one of a myriad of unappealing ways. Prior to the advent of breweries and taverns in America, beer was brewed at home.

Early American brewers took malted barley and cracked it by hand. They would then steep, or soak, the grains in boiling water. They called the process mashing. Mashing allowed the brewer to extract the sugars from the barley. Brewers took the mash they had created, which had the consistency of oatmeal, and dumped it into a sawed-off whiskey barrel. The modified tub acted as a sieve, filtering the sugary liquid from the grain. The colonial brewer returned the strained liquid to the boil kettle, or the copper as it was called, for a 2-hour boiling. He added hops, chilled the brew, sprinkled it with yeast, and drained the final product into wooden kegs. The brewer then placed those kegs in a cellar for three weeks to a month.

Brewing did not always turn out well. For some Early American brewers, beer went bad quite often. In a letter dated 1623, George Sandy of the Virginia colony wrote, "It would well please the country to hear he had taken revenge of Dupper for his Stinking [sic] beer, which hath been the death of 200." Like most food or beverage products, beer is not immune to bacterial growth or becoming rank from improper brewing practices.

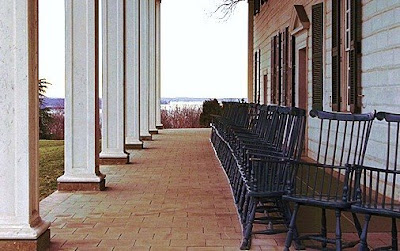

By the 1700s beer was big business, although recipes differed. Farmers planted fields of barley and hops, beer's chief ingredients, to help keep the liquid flowing. Many people, especially rich gentlemen, built private brew houses, handcrafting most of the equipment from wood (except the copper kettle, of course). Thomas Jefferson and George Washington built breweries on their plantations. In fact, Jefferson's wife brewed 15 gallons of low-alcohol beer every two weeks.

Thomas Jefferson grew hops at Monticello for brewing, and also purchased them in fairly large quantities from others. Jefferson's memorandum books record a handful of purchases by both Jefferson and his wife in the early 1770s, mostly from local slaves. These hops were most likely used for brewing batches of "small beer."

George Washington’s instructions for making Small Beer:

Take a large Siffer [Sifter] full of Bran Hops to your Taste. Boil these 3 hours. Then strain out 30 Gall[ons] into a cooler, put in 3 Gall[ons] Molasses while the Beer is Scalding hot or rather draw the Molasses into the cooler & St[r]ain the Beer on it while boiling Hot. Let this stand till it is little more than Blood warm. Then put in a quart of Yea[s]t if the Weather is very Cold, cover it over with a Blank[et] & let it Work in the Cooler 24 hours then put it into the Cask — leave the bung open till it is almost don[e] Working — Bottle it that Week it was Brewed. — From a notebook (c. 1757) kept by George Washington

Jefferson also mentions hops in Notes on the State of Virginia, in Query VI, in a list of native esculent plants: "Wild hop - humulus lupulus."1 Regarding his own culture of the plant, Jefferson first lists hops in his "Objects for the garden" in 1794.

In 1812, Jefferson began brewing beer at Monticello on a large scale, and that same year he lists hops in his garden calendar. They also appear on his garden "agenda" for 1813. Despite growing hops, Jefferson continued to record purchases of hops from various other sources until 1820.

Amelia Simmons 1796 American Cookery, the first cookbook written by an American, using ingredients available to Americans, gives a recipe for spruce beer containing hops, water, molasses and “essence of spruce.” (The essence was produced by boiling the young fresh shoots of the spruce tree and reducing the liquid to a concentrated extract.)

In 1824, Mary Randolph included a similar recipe for spruce beer in The Virginia Housewife, calling for a handful of hops, and twice as much of the chippings of sassafras root, one gallon of molasses, two spoonfuls of essence of spruce, two of powdered ginger, and one of powdered allspice.

Eliza Leslie's, 1837 Directions for Cookery included recipes for spruce beer, ginger beer, molasses beer and sassafras beer, (as well as for fox grape shrub and cherry bounce): Sassafras Beer– Have ready two gallons of soft water; one quart of wheat bran; a large handful of dried apples; half a pint of molasses; a small handful of hops; half a pint of strong fresh yeast; and a piece of sassafras root the size of an egg… Leslie gives instructions for boiling the mixture, straining through a hair sieve, and putting into open jugs to ferment.

Even up into the later 1800s, some households were producing their own beer. This recipe for beer comes from a community cookbooks, Housekeeping in the Blue Grass compiled by the Southern Presbyterian Church Missionary Society of Paris, Kentucky, in 1875: Beer- Two quarts of wheat bran, two and a half gallons of water, a few hops, one pint of molasses, and one pint of yeast. –Miss Kate Spears.

Spruce and molasses, along with hops and malt, continued to be employed in home brewing well into the 19th century. Lydia Maria Child, the noted American abolitionist, women’s rights activist, journalist, Indian rights advocate, and successful author, uses all of these ingredients and more in her recipes from The Frugal Housewife, which was reprinted at least 35 times between 1829 and 1850:

Beer– Beer is a good family drink. A handful of hops, to a pailful of water, and a half-pint of molasses, makes good hop beer. Spruce mixed with hops is pleasanter than hops alone. Boxberry, fever-bush, sweet fern, and horseradish make a good and healthy diet-drink. The winter evergreen, or rheumatism weed, thrown in, is very beneficial to humors. Be careful and not mistake kill-lamb for winter-evergreen ; they resemble each other. Malt mixed with a few hops makes a weak kind of beer ; but it is cool and pleasant ; it needs less molasses than hops alone. The rule is about the same for all beer. Boil the ingredients two or three hours, pour in a half-pint of molasses to a pailful, while the beer is scalding hot. Strain the beer, and when about lukewarm, put a pint lively yeast to a barrel. Leave the bung loose till the beer is done working; you can ascertain this by observing when the froth subsides. If your family be large, and the beer will be drank rapidly, it may as well remain in the barrel; but if your family be small, fill what bottles you have with it; it keeps better bottled. A raw potato or two, cut up and thrown in, while the ingredients are boiling, is said to make beer spirited.

New Yorker John Nicholson wrote about early American beer in

The Farmer's Assistant in 1820,

"To make Spruce beer. Boil some spruce boughs with some wheat-bran till the water tastes sufficiently of the spruce; strain the water, and stir in at the rate of 2 quarts of molasses to a half-barrel; work it with the emptyings of beer, or with yeast if you have it. After working sufficiently, bung up the cask, or, which is better, bottle its contents.

"To make Molasses beer. Take 5 pounds of molasses, half a pint of yeast, and a spoonful of powdered ginger; put these into a vessel, and pour on 2 gallons of scalding hot soft water; shake the whole till a fermentation is produced; then add of the same kind of water sufficient to fill up your half barrel...Let the liquor ferment about twelve hours; then bottle it, with a raisin or 2 in each bottle.

"If honey instead of molasses be used, at the rate of about 12 pounds to the barrel, it will make a very fine beverage, after having been bottled a while.

"If honey instead of molasses be used, at the rate of about 12 pounds to the barrel, it will make a very fine beverage, after having been bottled a while.

"To make Beer with Hops. Take 5 quarts of wheatbran and three ounces of hops, and boil them 15 minutes in 15 gallons of water; strain the liquor; add 2 quarts of molasses; cool it quickly to about the temperature of new milk, and put it into your half barrel, having the cask completely filled. Leave the bung out for 24 hours, in order that the yeast may be worked off and thrown out; and then the beer will be fit for use. About the 5th day, bottle off what remains in the cask, or it will turn sour, if the weather be warm. If the cask be new, apply yeast, or beer-emptyings, to bring on the fermentation; but, if it has been in this use before, that will not be necessary.

"Yeast, particularly the whiter part, is much fiter to be used for fermenting, than the mere grounds of the beerbarrel ; and the same may be observed, in regard to its use in fermenting dough for bread.

"To recover a cask of stale Small beer. Take some hops and some chalk broken to pieces; put them in a bag, and put them in at the bunghole, and then stop up the cask closely. Let the proportion be 2 ounces of hops and a pound of chalk for a half-barrel.

"To recover a cask of stale Small beer. Take some hops and some chalk broken to pieces; put them in a bag, and put them in at the bunghole, and then stop up the cask closely. Let the proportion be 2 ounces of hops and a pound of chalk for a half-barrel.

"To cure a cask of Beer. Mix 2 handsful of beanflour with one handful of salt, and stir it in.

"To feed a cask of Beer. Bake a rye-loaf well nutmeged; cut it in pieces, and put it in a narrow bag with some hops and some wheat, and put the bag into the cask at the bunghole.

"To clarify Beer. For a half-barrel, take about 6 ounces of chalk, burn it, and put it into the cask. This will disturb the liquor and fine it in 24 hours. It is also recommended, in some cases, to dissolve some loaf-sugar and add to the above ingredients.

"To clarify Beer. For a half-barrel, take about 6 ounces of chalk, burn it, and put it into the cask. This will disturb the liquor and fine it in 24 hours. It is also recommended, in some cases, to dissolve some loaf-sugar and add to the above ingredients.

"We omit going into any description of the method of making strongbeer, as the necessity for it among Farmers, as a household beverage, seems to be greatly obviated by that of smallbeer, which is much less intoxicating, and by cider, a stronger drink, which is readily afforded from apple-orchards, which are more or less natural to almost every part ot the United States, except a little of its southern border, where the grape can be cultivated to advantage...

"We omit going into any description of the method of making strongbeer, as the necessity for it among Farmers, as a household beverage, seems to be greatly obviated by that of smallbeer, which is much less intoxicating, and by cider, a stronger drink, which is readily afforded from apple-orchards, which are more or less natural to almost every part ot the United States, except a little of its southern border, where the grape can be cultivated to advantage...

"It is indeed true, that many Farmers in Great Britain brew their own strongbeer; but there is but little of that country where apple-orchards are natural...It is an expensive liquor tor the Farmer to make much use of, as it requires 4 bushels of malt to make a barrel, even of common ale, and 8, for a barrel of beer ot the strongest kind."

"If honey instead of molasses be used, at the rate of about 12 pounds to the barrel, it will make a very fine beverage, after having been bottled a while.

"If honey instead of molasses be used, at the rate of about 12 pounds to the barrel, it will make a very fine beverage, after having been bottled a while. "To recover a cask of stale Small beer. Take some hops and some chalk broken to pieces; put them in a bag, and put them in at the bunghole, and then stop up the cask closely. Let the proportion be 2 ounces of hops and a pound of chalk for a half-barrel.

"To recover a cask of stale Small beer. Take some hops and some chalk broken to pieces; put them in a bag, and put them in at the bunghole, and then stop up the cask closely. Let the proportion be 2 ounces of hops and a pound of chalk for a half-barrel. "To clarify Beer. For a half-barrel, take about 6 ounces of chalk, burn it, and put it into the cask. This will disturb the liquor and fine it in 24 hours. It is also recommended, in some cases, to dissolve some loaf-sugar and add to the above ingredients.

"To clarify Beer. For a half-barrel, take about 6 ounces of chalk, burn it, and put it into the cask. This will disturb the liquor and fine it in 24 hours. It is also recommended, in some cases, to dissolve some loaf-sugar and add to the above ingredients. "We omit going into any description of the method of making strongbeer, as the necessity for it among Farmers, as a household beverage, seems to be greatly obviated by that of smallbeer, which is much less intoxicating, and by cider, a stronger drink, which is readily afforded from apple-orchards, which are more or less natural to almost every part ot the United States, except a little of its southern border, where the grape can be cultivated to advantage...

"We omit going into any description of the method of making strongbeer, as the necessity for it among Farmers, as a household beverage, seems to be greatly obviated by that of smallbeer, which is much less intoxicating, and by cider, a stronger drink, which is readily afforded from apple-orchards, which are more or less natural to almost every part ot the United States, except a little of its southern border, where the grape can be cultivated to advantage...

+The+Hervey+Converstion+Piece+The+Holland+House+Group.jpg)

+Francis+Vincent,+his+Wife+Mercy,+and+Daughter+Ann,+of+Weddington+Hall,+Warwickshire.jpg)

+The+Thomas+Cave+Family.jpg)

.jpg)

+Mr+and+Mrs+Van+Harthals+and+Son.jpg)

+Henry+Fiennes+Clinton,9th+Earl+of+Lincoln,+with+his+wife+Catherine+and+his+son+George+on+the+great+terrace+at+Oatlands+(2).jpg)

+An+Angling+Party+(perhaps+The+Willyams+Family+at+Carnanton).jpg)

%2C%2Bwith%2BHis%2BFamily%2C%2Bin%2Bthe%2BGarden%2Bof%2BGrove%2BHill%2C%2BCamberwell.jpg)

.+The+Grymes+Children-+Lucy+1743-1830,+Philip+1746-1805,+Jno+Randolph+1747-96,+Chas+1748-+.+Virginia+Historical+Society,+Richmond.jpg)

+Richard,+Mary,+and+Peter,+Children+of+Peter+and+Mary+du+Cane+Detail.jpg)

+The+James+Family.jpg)

.jpg)

+The+Mathew+Family+at+Felix+Hall,+Kelvedon,+Essex.jpg)

+A+Group+of+Gentlemen.jpg)

.+The+William+Denning+Family+vine+dog+urn+wall+chair.jpg)

+Detail.+Rice+Hope+Taken+from+One+of+the+Rice+Fields.+South+Carolina.+2.jpg)

.+The+Hartley+Family..jpg)

.+The+Enoch+Edwards+Family..jpg)