Spreading Gardening from the Gentry to the Townsfolk

1809 Anne-Marguérite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville (French, ca. 1749–1849) The fairly modest Moreau House in New Jersey including statues, flower pots, & a little girl with a rake.

One of Irish immigrant seedsman & author Bernard M’Mahon's (1775-1816) goals, as he was writing his 1806

The American Gardener's Calendar was to spread gardening to urban shopkeepers & artisans. These townsfolk, recently arrived from the farms & plantations of America's 18th-century agrarian economy or from abroad, were finding themselves with disposible income but living in unfamiliar, crowded city streets. During the Revolution, British naval blockades cutting off imports from abroad forced farmers & planters to make their own textiles & home goods, as they severely reduced the tobacco & grains they had been producing for export. Markets in northern cities became the source for credit & for formerly imported products. By the last decade of the 18th-century, merchants in towns like Baltimore controlled the merchandise supply lines in & out of the region from Europe, nothern American towns, & the West Indies. Sons & daughters of farmers & planters moved to town to work in the new economy. Only a small patch of land was available to them there to plant gardens, but M'Mahon realized that the more folks who gardened, the more seeds, plants, tools, & books he would sell. He was one of the new garden businessmen from abroad.

+Walk+at+a+Corner+of+Greenwich+in+New+York+City.+1810.+Baroness+Hyde+de+Neuville..jpg)

1810 Anne-Marguérite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville (French, ca. 1749–1849) Corner Greenwich

1810 Anne-Marguérite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville (French, ca. 1749–1849) Detail Corner Greenwich

1810 Anne-Marguérite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville (French, ca. 1749–1849) Detail Corner Greenwich

America, Baroness Hyde de Neuville, (Anne Marguerite Henriette de Marigny Hyde de Neuville), arrived in New Jersey from France, with her husband, in 1807. They were escaping the results of the French Revolution, as the privileged fled from a vindictive egalitarianism. They would find themselves in a new republic, where those from the farms & plantations were making their way west or flooding into the growing towns along the Atlantic coast. The Baroness would document in watercolors the new egalitarian life in the former British colonies during the Federalist era, especially in its growing towns.

1807 Anne-Marguérite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville (French, ca. 1749–1849) View of Utica (New York) from the Hotel

After the French Revolution, she secured the life & safe passage of her husband, who was a royalist, by traveling alone across Europe to intercede with Napoleon. In order for the couple to escape from France, she posed as her husband’s mother, until they arrived safely in the U.S. They settled on a merino sheep farm in the New Brunswick area. For a number of years, the couple journeyed to New York City & to various settlements along the Hudson. The Baroness recorded what she saw. She saw few town gardens. America's seed dealers & nurserymen were working hard to change that.

Anne-Marguérite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville (French, ca. 1749–1849)

Many townsfolk gardened in traditional geometric plots, usually defined by walkways on their smaller lots.

Craftsmen such as William Faris (1729-1804), who lacked sufficient space on their small town lots to develop classical falling terraces but wished to copy the designs used by the grander families, adopted traditional geometric garden styles that more closely resembled the miniature formal garden adaptations of the Dutch. Land in Holland was often only a thin layer of soil unable to support the deep roots of trees, so the Dutch planted low hedges instead. As the Dutch population grew, their gardens became more compact as well. While the sophisticated French thought flowers too common & certainly not as controllable as the gravel they used in their parterres, the Dutch were avid flower growers. That tradition appealed to America's new city dwellers.

1817 Anne-Marguérite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville (French, ca. 1749–1849) F St DC

After Napoleon was defeated & the King restored to the throne, the de Neuvilles returned to France. However, the Baron was rewarded for his loyalty & named French Ambassador to the United States, so the couple returned to take up residency in the new capital, Washington. Baroness Hyde de Neuville continued to produce watercolors depicting life during the Federalist era.

1818 Anne-Marguérite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville (French, ca. 1749–1849) Home in Washington to the French ambassador

American devotion to compact urban flower gardens could be particularly profitable for M’Mahon, who sold flower seeds, plants, & bulbs, devoted much of his landmark book to the cultivation of flowers.

1813 Anne-Marguérite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville (French, ca. 1749–1849) The Cottage

Urban Americans were appreciative of their little town gardens. In Philadelphia, Quaker Elizabeth Drinker (1735-1807) wrote in her diary on April 10, 1796,

“Our Yard & Garden looks more beautiful, the Trees in full Bloom, the red & white blossoms intermix’d with the green leaves, which are just putting our flowers of several sorts blom in our little Garden--what a favour it is, to have room enough in the City…many worthy persons are pent up in small houses with little or no lotts, which is very trying in hott weather."

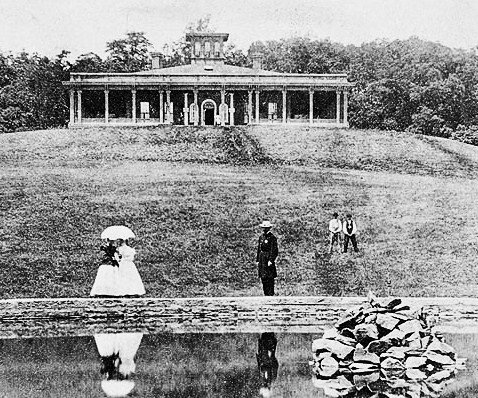

Baltimore Country Seat Druid Hill by Francis Guy

Baltimore Country Seat Druid Hill by Francis Guy Photo of Druid Hill Later in the 19th Century

Photo of Druid Hill Later in the 19th Century

+Walk+at+a+Corner+of+Greenwich+in+New+York+City.+1810.+Baroness+Hyde+de+Neuville..jpg)

+Corner+in+Greenwich,+NYC(2).jpg)

+(2).jpg)

.jpg)

+F+St+DC+1817.jpg)

+Home+in+Washington+in+1818+to+the+French+ambassador,+Baron+Hyde+de+Neuville,.jpg)

+Sara+Gansevoort+(1718-1731).jpg)

+Mrs+Thomas+Jones.jpg)

+Ann+&+Sarah+Gordon.jpg)

.jpg)

+Mary+&+Elizabeth+Royall+with+dog+and+bird.jpg)

+Phil+Acad+of+Fine+Arts+2.jpg)

.jpg)

.Young+Lady+with+a+Bird+and+Dog+1767.jpg)

.+Detail+of+Boy+with+Bird..jpg)

.+Detail+of+Boy+with+Cardinal..jpg)

_+Jerusha+Benedict+(Ives).jpg)

+Francis+O+Watts+with+Bird.jpg)

+Two+Children+at+Play+with+White+Bird+1805.jpg)

+Girl+with+a+Dove+1810.jpg)

+Boy+with+Bird+c+1815.jpg)