George Washington cared deeply about the appearance of his gardens, in both style & type of flora, & closely supervised the planting process at Mount Vernon. He demonstrated his love of the United States through the types of native flora that he planted on his estate. After Washington retired, first from war & then from politics, he fulfilled the image of a gentleman planter, using Mount Vernon as his own personal statement of independence & republican simplicity.

Washington loved his gardens & was constantly changing the plants used at Mount Vernon. There is little evidence to suggest, however, that he was the one gardening. There were many gardeners who worked at Mount Vernon, several of whom were indentured servants. For example, letters written from Washington to his estate manager, Lund Washington, & to John Washington, an acquaintance from King George City, Virginia, reveal that Philip Bateman served as the primary gardener at Mount Vernon between 1773 & 1785...

George Washington purchased Bateman as an indentured servant for £35 in 1773, but continued to employ his services long after the term of indenture had ended... Records indicate that an individual with the last name Bateman was still at the Mount Vernon Estate until 1787, although there is no record to confirm that it was the same Bateman. On March 20, 1773, George Washington wrote to thank John Washington for finding him a promising gardener.3 Evidence in Washington's diaries suggests that Bateman stayed at least until December 1785, around the same time Lund Washington was preparing to end his tenure as the estate manager of Mount Vernon... There is a possibility that Bateman stayed at Mount Vernon longer, perhaps under the name Philip Bater, who on April 23, 1787, agreed to continue to work at Mount Vernon for at least one more year...

Very little is known about Bateman aside from the fact that he was the gardener at Mount Vernon from 1773 to at least 1785. Although Lund Washington appreciated Bateman's talents, he did not think highly of the gardener's intellect. In October 1783, Lund Washington wrote to George Washington: "As to Bateman (the Old Gardener) I have no expectation of his ever seeking Another home—indulge him in getg Drunk now & then, & he will be happy—he is the best kitchen Gardener to be met with..." Bateman was clearly loyal to the Washingtons & to Mount Vernon, but from the very few letters & records that mention his name it is difficult to ascertain his fate after he ended his work at Mount Vernon.

After Bateman's departure from Mount Vernon, George Washington hired a German gardener named Johann (John) Christian Ehlers who worked on the estate from 1789 to 1797. Although Washington employed Ehlers for nearly ten years, he was constantly troubled by Ehler's work ethic & drinking habits. In 1792, Washington warned his estate manager at the time, Anthony Whiting, about Ehlers: "It is my desire also that Mr. Butler will pay some attention to the conduct of the Gardener & the hands who are at work with him; so far as to see that they are not idle; for, though I will not charge them with idleness, I cannot forbear saying . . . that the matters entrusted to him appear to me to progress amazingly slow..."

Ehlers evidently did not reform his behavior. In December 1793, Washington scolded the gardener, writing, "I shall not close this letter without exhorting you to refrain from spiritous liquors—they will prove your ruin if you do not … Don’t let this be your case. Shew yourself more of a man, & a Christian, than to yield to so intolerable a vice; which cannot, I am certain (to the greatest lover of liquor) give more pleasure to sip in the poison (for it is no better) than the consequences of it in bad behaviour at the moment, & the more serious evils produced by it afterwards, must give pain..." Washington ultimately parted ways with Ehlers in 1797.

While Ehlers was still employed by Washington, another gardener named John Gottleib Richler also worked at Mount Vernon. Richler was a German servant indentured for three years in return for Washington paying for his passage from Germany to the United States... Otherwise not much is known about Richler [not Ehlers], who presumably left Mount Vernon after his term of indenture ended.

There were many other gardeners who worked at Mount Vernon, but their personal information is scarce. Two of these gardeners were David Cowan & William Spence. David Cowan worked for Washington for a little over a year between 1773 & 1774. William Spence was hired to work at Mount Vernon as a gardener in 1797, & stayed on after Washington's death in 1799.

There is no evidence that George Washington did any physical gardening himself at Mount Vernon, but his influence on activities was still apparent. His designs determined what plants were included & how the gardens appeared. Washington was directly involved in the development & redesigning of the gardens around the mansion, especially during his two separate retirements between 1784 & 1789 & from 1779 to 1799...

Washington contributed to the look of several natural spaces at Mount Vernon, including, the vista approaching the house, the Bowling Green, & the upper & lower walled gardens. For each garden area, Washington specified the types of plants & features that he wanted. In the Bowling Green, for example, Washington had the area shaped perfectly flat, using rollers to compress the earth & planted with velvety English grass to create a lush setting.

Surrounding the Bowling Green, Washington chose shrubs & trees planted around the walkways to reflect his design aesthetic. Washington desired to have native North American plant species in his gardens to represent the splendor of flora found in the United States. In his letters, Washington wrote that he wanted "philadelphus coronarius, as sweet flowering shrub (called mock Orange)," "Pinus Strobus," "Prunis Divaricata," "Hydrangia arborescens," & "Laurus nobilis..." Washington exercised similar influence over each of Mount Vernon’s gardens.

Research plus images & much more are available from Geo Washington's (1732-1799) home Mount Vernon website, MountVernon.org.

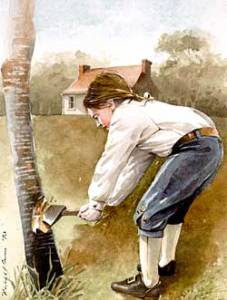

The moment anyone mentions trees and George Washington, you probably think of the famous Cherry Tree Story. However, this tale of young George taking a hatchet to his father cherry tree and, when confronted about the act, asserting "I cannot tell a lie" is probably just that -- a story meant to demonstrate the integrity of the Father of Our Country. In reality, the trees of Ferry Farm have a much more fascinating history. Their story reflects, on a small local scale, vast environmental changes in eastern North America and shifting American attitudes toward the environment throughout the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries.

The moment anyone mentions trees and George Washington, you probably think of the famous Cherry Tree Story. However, this tale of young George taking a hatchet to his father cherry tree and, when confronted about the act, asserting "I cannot tell a lie" is probably just that -- a story meant to demonstrate the integrity of the Father of Our Country. In reality, the trees of Ferry Farm have a much more fascinating history. Their story reflects, on a small local scale, vast environmental changes in eastern North America and shifting American attitudes toward the environment throughout the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries.