A History of Trees at Ferry Farmby ferryfarmandkenmore |

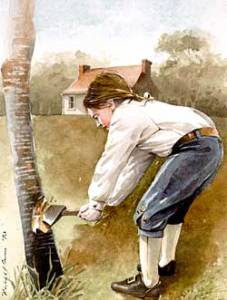

The moment anyone mentions trees and George Washington, you probably think of the famous Cherry Tree Story. However, this tale of young George taking a hatchet to his father cherry tree and, when confronted about the act, asserting "I cannot tell a lie" is probably just that -- a story meant to demonstrate the integrity of the Father of Our Country. In reality, the trees of Ferry Farm have a much more fascinating history. Their story reflects, on a small local scale, vast environmental changes in eastern North America and shifting American attitudes toward the environment throughout the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries.

The moment anyone mentions trees and George Washington, you probably think of the famous Cherry Tree Story. However, this tale of young George taking a hatchet to his father cherry tree and, when confronted about the act, asserting "I cannot tell a lie" is probably just that -- a story meant to demonstrate the integrity of the Father of Our Country. In reality, the trees of Ferry Farm have a much more fascinating history. Their story reflects, on a small local scale, vast environmental changes in eastern North America and shifting American attitudes toward the environment throughout the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries.

Today, we see wilderness as a good thing that needs protected and preserved. But in the 1700s, Europeans settlers saw wilderness as a bad thing. Preeminent environmental historian William Cronon notes, Europeans described wilderness as “’deserted,’ ‘savage,’ ‘desolate,’ ‘barren’—in short, a ‘waste,’.” People did not look at forests, deserts, or mountains as places to protect and visit. Instead, they were places to be feared and tamed.

The opposite of wilderness was the managed landscape of Europe. In cities, towns, and farms, Europeans tried to control nature and make it follow humanity’s rules. These efforts to tame the wilderness were transplanted to colonial plantations in the Americas.

The first step in building a plantation and taming the wilderness was clearing the land for farming. Huge numbers of trees were cut down to do this. On top of that, trees were cut down to make almost everything people of the 1700s and 1800s used and owned. Furthermore, they were also cut down to do many everyday tasks.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the wood from trees was…

- used as the main architectural building material in houses, most other structures, farm buildings, fences, and more

- used to build ships, boats, ferries, bridges, carriages and wagons that moved people and things from place to place

- used to make everyone’s furniture (beds, chairs, tables, desks, cabinets, and trunks) as well as many household items and farming tools

- used as fuel for the fires needed to cook, heat, and even to make candles and soap. A colonial home needed at least 40 cords of wood for heating and cooking over the course of a year.

According to the U.S. Forest Service, the area that would become the United States had just over 1 billion acres of forest before European settlement. By 1910, the U.S. had a total of just over 700 million acres. The 300 million acres of trees cut down was mostly in the eastern portion of the country.

These large scale trends can be seen on a small scale at Ferry Farm. The European settlers who lived here, including the Washingtons, cut down a significant number of trees but not so many that there weren’t still quite a few standing when John Gadsby Chapman painted Ferry Farm’s landscape in 1833.

We also have archaeological evidence showing the locations of trees during the Washington era. This past summer in the yard north of the Washington house replica archaeologists uncovered “soil stains” left after trees fell in the past. Soil stains are where the soil is a slightly different color than surrounding areas and indicate where people filled in holes created by uprooted trees. In other words, such soil stains indicate that a tree once stood there.

In some cases, our archaeologists found that the holes were filled in multiple episodes, indicating that the soil settled and new dirt was later added or the person filling the hole borrowed different dirt of different colors from multiple locations. By excavating the soil from these soil stains and analyzing the artifacts, we can tell around when the holes were filled.

One very large tree left the sizable soil stain – almost 5ft x 5ft – pictured above. Based on artifacts found in its soil, the hole was filled during the mid-19th century. We can tell by the size of the stain that the tree was quite mature. Together, these facts are evidence of a tree that grew just 40 feet north of the original Washington house during the time George and his family lived at Ferry Farm. This discovery gives us another detail about the landscape so it can eventually be accurately recreated just as we did the main house.

Finally, Ferry Farm archaeologists learned from these tree features and from the lack of other features in this yard that the area was well-kept. In the 18th century, this portion of the landscape was probably well-maintained because it was visible from Fredericksburg across the river.

This tree fell sometime in the 19th century and it was not the only one at Ferry Farm or across the country. Indeed, deforestation at Ferry Farm and nationwide grew more rapid and widespread in the 1800s as “clearing of forest land in the East between 1850 and 1900 averaged 13 square miles every day for 50 years; the most prolific period of forest clearing in U.S. history.”

In the 1860s, the Civil War exacerbated deforestation at Ferry Farm and throughout Stafford County. Hundreds of thousands of Union Army soldiers radically altered the local environment to get the wood they needed for cooking and heating, to help build their fortifications and pontoon bridges, and even to build shelters. During winter lulls in fighting, 18th and 19th century armies did not camp in tents. The soldiers built small log cabins. By war’s end, Ferry Farm and Stafford County were nearly treeless as seen in the two photos of Ferry Farm below taken in the decades after the war ended.

While deforestation sped up in the 1800s, that century also began a changing of people’s attitudes toward the environment. As Cronon explains, “The wastelands that had once seemed worthless had for some people come to seem almost beyond price. That Thoreau in 1862 could declare wildness to be the preservation of the world suggests the sea change that was going on. Wilderness had once been the antithesis of all that was orderly and good—it had been the darkness, one might say, on the far side of the garden wall—and yet now it was frequently likened to Eden itself.” Wilderness was to be treasured, not feared.

As the 19th century turned into the 20th, wilderness, nature, and the environment were increasingly seen as special and deserving of protection and preservation, sparking the creation of national and state parks, government agencies like the Forest Service, private conservation groups such as the Sierra Club, and, in 1872, the very first Arbor Day.

We can see the impact of new attitudes toward the environment at Ferry Farm in photos below. The top one from the 1930s, a period of intense conservation efforts nationwide, shows trees starting to appear once again while the other from 2017 shows trees on a portion of Ferry Farm stretching out as far as the eye can see to the north.

The early 20th century saw the nadir of American deforestation in 1910. But since that year, forest acres in the U.S. have largely held steady [PDF]. The new conservation ethic symbolized in the practice of planting trees to replace those cut down, the reduced use of wood as a building material and fuel source, the need for less farm land, and the movement of people from rural to urban areas (all of which present their own challenges to the environment) have provided a reprieve for America’s forests.

While George’s mythical chopping of the Cherry Tree is the most well-known tale about trees at Ferry Farm, the more important and fascinating story is how the 300 hundred year history of trees at Ferry Farm reflects broader post-settlement environmental changes in North America and how the Americans who made those changes grew to see the world differently.

Zac Cunningham

Manager of Educational Programs

Manager of Educational Programs

Elyse Adams, Archaeologist

Archaeology Lab Technician

Archaeology Lab Technician