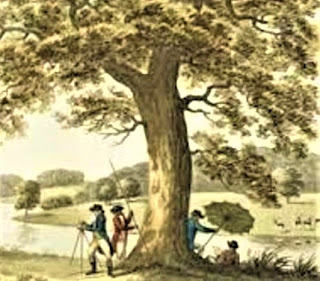

Charles Fraser (1782-1860) Golden Groves The Seat of Mrs (John) Sommers Stono River. Carolina Art Association Gibbes Museum, Charleston, South Carolina

Landowners in eighteenth century South Carolina tended to jeep one eye on the sun and the other on the latest, most fashionable garden design, as they planned the gardens and grounds around their homes. Carolina gardeners used the same traditional European design components as their fellow colonists up and down the Atlantic coast, but they seldom forgot to plan for the oppressive Carolina summer heat. Shady trees and cooling water played a large part in the colonial South Carolina garden design.

Trees - Alleys and Avenues

Garden planners charted walkways, alleys, and avenues to form the basic skeleton of their gardens. Most colonial British Americans called the entire outdoor area surrounding their living quarters “gardens.” Property owners often divided these garden areas into geometric beds for growing flowers and vegetables; yards for enclosing a variety of outdoor work; and larger turfed open areas for playing lawn games or visiting with friends and family.

South Carolinians especially enjoyed alleys of trees, because they offered cooling shade for year-round exercise. Alleys also directed the onlooker’s line of sight, defined garden compartments, and added ornament to the grounds. Gardeners usually planned an alley as a walkway bordered with single or double rows of trees or hedges. Alleys leading from a center door of a dwelling through the center of an adjoining garden were wider than subsidiary intersecting walkways.

Occasionally garden architects intentionally manipulated the perspective, so that the apparent size of an alley was lengthened by gradually narrowing the width of the alley towards the far end. Some gardeners called those walkways between beds of plants bordered by low-growing shrubs alleys.

On May 22, 1749, in Charleston, a landowner advertised,

A garden, genteelly laid out in walks and alleys, with flower-knots, & laid round with bricks” for sale in the

South Carolina Gazette.

Plantation owners in mid-eighteenth century South Carolina often employed even larger avenues of trees as well. Garden architects designed avenues as wide, straight roadways approaching plantation houses or public buildings lined with single or double rows of trees and often cutting through a lawn of grass. Planners left avenues wide enough for a horse or carriage to pass, and some were much wider with many being the width of the house. Avenues leading to the entrance façade of a dwelling were wider than subsidiary intersecting ones and often were wide enough that the entire façade of the house was visible from the far end. Usually a 200’ long avenue was about 14-15’ wide, a 600’ avenue was about 30-36’ wide, and a 1200’ long avenue was about 42-48’ wide. Gardeners occasionally manipulated the perspective of even these broad avenues as well, so that the apparent size of an avenue was lengthened by gradually narrowing the width of the avenue towards the far end. In the colonies, the term avenue also referred to a public tree-lined town street.

In May, 1743, Eliza Lucas Pinckney wrote from Charleston, "

I…cant say one word on the other seats I saw in this ramble, except the Count’s large double row of Oaks on each side of the Avenue that leads to the house--which seemed designed by nature for pious meditation and friends converse.”

Growing an avenue of trees took special planning and many years. Often the avenue of trees was planted years before the house was built on the property. On June 18, 1753, William Murray wrote to John Murray Esquire of Murraywhaithe in Charleston,

"By all means mention the fine Improvements of your garden & the fine avenues you’ve raised near the spot where you’r to build your new house.”

Twenty years later, commercial nurserymen promoted grown trees for sale to the Charleston public. On January 1, 1776, an advertisement in the

South Carolina and American General Gazette offered,

"For sale…Magnolia or Laurels fit for Avenues…any height from three feet to twenty.”

By this time a French visitor noted that avenues of trees lined the public streets of Charleston as well. He wrote in 1777,

"There are trees along most of the streets, but there are not enough of them to make it pleasant to promenade along the streets in the heat of the day.”

Nurseries growing trees for decoration and for food flourished in South Carolina. Planters usually enclosed private or commercial nursery gardens to grow young plants, especially fruit trees which were practical as well as ornamental. On June 5, 1736, landowner Daniel Wesshuysen advertised,

“A Plantation containing 200 Acres…An orchard well planted with peach, apple, cherry, fig and plumb trees; a vineyard of about two years growth planted with 1200 vines; a nursery of 5 or 500 mulberry trees about two years old, fit to plant out” in the

South Carolina Gazette.

Eliza Lucas Pinckney wrote in 1742,

"I have planted a large figg orchard with design to dry and export them. I have reckoned my expense and the prophets to arise from these figgs.” Nearly 20 years later in 1761 she was still fretting about a nursery when she wrote, "

I will endeavor to make amends and not only send the Seeds but plant a nursery here to be sent you in plants at 2 years old.”

David Ramsay noted that Henry Laurens’ Charleston garden was

“enriched with everything useful and ornamental that Carolina produced or his extensive mercantile connections enabled him to procure from remote parts of the world. Among a variety of other curious productions, he introduced olives, capers, limes, ginger, guinea grass, the alpine strawberry, bearing nine months in the year, red raspberries, blue grapes; and also directly from the south of France, apples, pears, and plums of fine kinds, and vines which bore abundantly of the choice white eating grape called Chasselates blancs." Gardeners up an down the Atlantic seacoast experimented with growing grapes for wine throughout the eighteenth century.

Drayton Plantation

Trees - Clumps, Groves, and Thickets

Owners of larger plantations also used clumps of trees for shade and decoration. They often intentionally planted clusters of trees or thickets of shrubs on the pleasure grounds near their dwellings to relieve the monotony of open ground. Some South Carolinians were lucky enough to have their clumps ready made. Rochefoucauld-Liancourt noted on his 1796 visit to

Drayton Hall,

"The Garden here is better laid out…in order to have a fine garden, you have nothing to do but to let the trees standing here and there, or in clumps, to plant bushes in front of them, and arrange the trees according to their height. Dr. Drayton’s father…began to lay out the garden on this principle and his son…has pursued the same plan."

Drayton Plantation

Trees - Bird-songs, Dovecotes

Landowners also took advantage of shady groves, which were small clusters of large, spreading shade trees either occurring naturally and intentionally left in the landscape or purposefully planted in the pleasure grounds near a swelling in the eighteen century. Usually the term grove referred to large trees whose branches produced food attracting local songbirds. At

Crowfield Eliza Lucas Pinckney noted

“a thicket of young tall live oaks where a variety of Airry Chorristers pour forth their melody.”

Birds were prized in South Carolina for both their songs and their taste. In the South Carolina Gazette on June 5, 1736, an advertisement for the sale of a plantation near Goose Creek offered

“A Plantation containing 200 Acres…a necessary-house neatly built, and above it a dove-house with nests for 50 pairs of pigeons.” And a 1772 ad in the

South Carolina and American General Gazette offered a plantation to be rented on the Ashley River near Charleston which contained

“two well contrived AVIARIES.”

Dovecote from Shirlet Plantation

But Eliza Lucas Pinckney also realized that to some colonials, a grove was a solemn place for spiritual contemplation. She worried about the symbolism when she wrote to a friend in 1742,

"You may wonder how I could in the gay season think of planting a Cedar grove, which rather reflects an Autumnal gloom and solemnity than the freshness and gayty of spring. But so it is…I intend then to connect in my grove the solemnity (not the solidity) of summer or autumn with the cheerfulness and pleasures of spring, for it shall be filled with all kind of flowers, as well wild as Garden flowers, with seats of Camomoil and here and there a fruit tree-oranges, nectrons, Plumbs."

A 1770s poem commemorates Alexander Garden’s

Otranto near Charleston,

“There midst the grove, with unassuming guise/But rural neatness, see the mansion rise!”

Trees - Wilderness, Mazes, and Labyrinths

South Carolina planters also adopted the European concept of wilderness for their pleasure grounds. A wilderness was an ornamental grove of trees, thicket, or mass of shrubbery intentionally set in a remote area of an eighteenth century pleasure ground, pierced by walks often forming a maze or labyrinth. Gardeners designed these green puzzles to confound guests as well as to offer cool exercise and privacy for courting.

On February 2, 1734, a landowner advertised in the

South Carolina Gazette "

To Be Let or Sold…A delightful Wilderness with shady Walks and Arbours, cool in the hottest seasons.” In May, 1743, Eliza Lucas Pinckney wrote of William Middleton’s

Crowfield, "

My letter will be of unreasonable length if I don’t pass over the mounts, Wilderness, etc.”

Plants - Beds, Edging, and Borders

However, trees and water did not push traditional garden components out of South Carolina gardens, especially those gardens on smaller plots in the town of Charleston. The flower knots mentioned in the May 22, 1749

South Carolina Gazette ad were flower beds formed into curious, intricate, and fanciful figures meant to please the eye especially when seen from a higher elevation such as a second story window, a mount, or a belvedere. Gardeners planned knot designs to be symmetrical. Sometimes they imitated the intricate shapes and patterns of the embroidery and cut work done by contemporary needleworkers. Flower knots were separated by paths and walks. The length of the flower know was generally about one and a third times the width, sometimes up to one and a half times but seldom longer. Beds separated by narrow paths were usually mirror images with patterns repeated at the ends and sides of quarters.

The term bed commonly was used to describe a level or smooth piece of ground in a garden, often somewhat raised for the better cultivation of the plants with which it is filled. Often beds were also referred to as squares, and they were usually designed in geometric shapes. Beds were separated by walkways and were often two, three, or four times the width of the central garden walks. Most beds were used to grow vegetables, although beds of flowers certainly existed in eighteenth century South Carolina. In 1756, Martha Daniell Logan advised,

“Trim and dress your Asparagus-Bed.”

Hedges

South Carolina gardeners also planted hedges or bushes or woody plants in a row to act as defensive fences, decorative land dividers, or windbreaks. On May 22, 1749 notice was given in the

South Carolina Gazette that land,

“Will be raffled…a garden, genteelly laid out in walks and alleys, with… cassini and other hedges.” Charles Fraser remembered that in the 1790s in Charleston, "

Watson’s gardens (was), a beautiful cultivated piece of ground, between Meeting and King-streets..adorned with shrubbery and hedges.”

Water - Basons and Canals

Water played a more important part in colonial South Carolina gardens than those to the north. Gardeners often dug basons or reservoirs of water into their pleasure grounds near their dwellings. In 1743 Eliza Lucas Pinckney wrote that at William Middleton’s

Crowfield,

“As you draw nearer…a spacious bason in the midst of a large green presents itself as you enter the gate that leads to the house..” Richard Lake advertised in the South Carolina Gazette on January 30, 1749,

“To be sold…a very large garden…with a variety of pleasant walks, mounts, basons, and canals.”

Some affluent south Carolina homeowners constructed artificial canals near their gardens and homes, some were even navigable. These waterways afforded irrigation, decoration, and fish. On May 22, 1749, the

South Carolina Gazette noted that in Charleston land was to be,

“raffled…a garden…at the end of which is a canal supplied with fresh springs of water, about 300 feet long, with fish.” A French traveler wrote in 1769 that at Middleton Place,

“the river which flows in a circuitous course, until it reaches this point, forms a wide, beautiful canal, pointing straight to the house.”

Water - Fountains, Cascades, Grottoes, and Bath Houses

More elaborate waterworks were also available to South Carolinians. On November 17, 1752, in the

South Carolina Gazette a professional garden architect offered,

“To Gentlemen…as have a taste in pleasure..gardens…may depend on laving them laid out, leveled, and drained in the most compleat manner, and politest taste, by the subscriber, who perfectly understands…erecting water works…fountains, cascades, grottos.” A cascade is an artificial rocky waterfall that noisily breaks the water as it flows over stone steps. In the eighteenth century, cascades usually were designed so that the water splashed over evenly stepped stone breaks with a slight lip on the top of each course. A grotto is an artificial subterraneous cavern meant to add mystery, ornament, coolness, bathing, and privacy to a garden.

Some South Carolina grounds contained bath houses sitting ready for a cooling dip. In 1733 an ad in the

South Carolina Gazette noted

“A Plantation about two Miles above Goose-Creek Bridge..[had] frames, Planks & to be fix’d in and about a Spring within 3 Stones throw of the House, intended for a Cold Bath, and a House over it.”

Charles Fraser (1782-1860). Entrance to Ashley Hall with Fishpond near Charleston, South Carolina.

Water - Fish Ponds

But by far the most popular South Carolina garden water decoration was also the most practical, a fish pond. Landowners usually dug these ponds close to their homes to serve as an artificial fresh water reservoir stocked with fish. On August 4, 1733 an advertisement in the

South Carolina Gazette noted,

“To be sold…a garden on each side of the House…a fish-pond well stored with pearch, roach, pike, eels, and cat-fish.” In the same paper on June 5, 1736 another ad told of a

“Plantation containing 200 Acres…An artificial fish-pond, always supplied by fresh water springs, and well stored with several sorts of fish.”

Eliza Lucas Pinckney described

Crowfield’s pond in May, 1743,

“a large fish pond with a mount rising out of the middle--the top of which is level with the dwelling house and upon it as a roman temple. On each side of this are, other large fish ponds.” (13) Another

South Carolina Gazette notice on July 13, 1745 advertised,

“To be sold…six Acres of Land, with a Dwelling house, Kitchen, two Summer houses, a large Garden and a Fish Pond.” A similar

South Carolina Gazette ad on July 9, 1748, noted property,

“TO BE SOLD…a beautiful Pond, supplied with Fish at the End of the Garden.” Richard Lake’s January 30, 1749

South Carolina Gazette notice also promoted

“a very large garden…with a large fish-pond.” Again on May 22 of 1749 a South Carolina Gazette ad touted

“a kitchen garden, at the end of which is a canal supplied with fresh springs of water, about 300 feet long, with fish.”

On June 18, 1753, William Murray advised John Murray Esquire of

Murraywhaithe of Charleston,

“You’ll certainly dig a Fish pond & another for geese & Ducks & one Swan.” Charles Fraser remembered French Quarter Creek near Charleston as the Seat of the Lake Bishop Smith

“Brabant, or Brabants…having a fine garden, shrubbery and ornamental lake…long known as ‘the Bishop Fish Pond’.”

Plants - Greenhouses and Botanical

Some South Carolina gardeners planted tender plants in wooden-box beds and pots in glass greenhouses where delicate plants could be pampered away from winter weather. An advertisement in the

South Carolina Gazette on November 14, 1748 offered a,

“Dwelling-house…also a large Garden, with two neat Green Houese for sheltering exotic Fruit Trees, and Grape-Vines.” Exotic plants captured the fancy of colonials early in the century; and by the end of the eighteenth century, formal botanical gardens dotted the Atlantic coast. These were both outdoor and indoor, public and private garden areas, where proud collectors displayed a variety of curious plants for purposes of science, education, status and art.

One notice in the

Charleston Courier on May 11, 1807 extolled the

“Botanick Garden of South Carolina…as large a collection of plants, as any garden in the United States, and it is peculiarly rich in rate and valuable exoticks…Lovers of science…acquire a knowledge of the most beautiful and interesting of the works of nature. The Florist may be gratified with viewing the productions of the remotest clime, and the Medical Botanist with the objects of his study…affords an agreeable recreation both to those who visit it merely for amusement, and who seek…information.”

Sites and Sights - Seated, Command, Eminence,

Vistas and Prospects

Collecting rare plants gave the colonial gardener status, but even more important was where the owner built his home and how he designed and maintained the grounds surrounding it. South Carolina homeowners in the eighteenth century knew that their home and grounds were a direct reflection of themselves and other ability to control their affairs. The eighteenth century was the culmination of thousands of years of agrarian society. The nineteenth century would bring the industrial revolution. But until then, mankind based its economy on its ability to manipulate nature in order to raise an trade crops. The work day was measured by the rising and the setting of the sun. One strong storm or flood could ruin a year’s work. And when people could raise enough crops and food to sustain a comfortable life, they challenged nature even further by manipulating their outdoor environment into a living art form, a garden. Most societies even gave the garden religious symbolism. The garden was the balancing point between human control on the one hand and mystical nature on the other. In the garden one could create an idealized, highly personal order of nature and culture.

Visitors judged both towns and homes on where and how they were planned by their originators. Both houses and towns were esteemed if they were “seated” on the highest “eminences” with the most advantageous “prospects” and “vistas.” Lord Adam Gordon visited Charleston on December 8. 1764; and he declared that

“The Town of Charleston is very pleasantly Seated, at the conflux of two pretty rivers, from which all the Country product is brought down, and in return all imported goods are sent up the Country.” Towns and houses were noted to “command” vistas and prospects of the neighboring countryside. There was a component of inherent power in being able to survey and control the land around.

When Jedidiah Morse wrote his 1789

American Geography he noted that in Charleston,

"The streets from east to west extend from river to river, and running in a straight line…open beautiful prospects each way…These streets are intersected by others, nearly at right angles, and throw the town into a number of squares, with dwelling houses in front, and office houses and little gardens behind.”

Colonial men usually planned the home and garden sites and escorted visitors around the grounds; bit the colonial woman usually managed the maintenance of the garden once it was in place. Henry Laurens noted in 1763,

“Mrs. Laurens is greatly disappointed, as she is not yet able…to get into our new House & become mistress of that employment which she most delights in, the cultivating & ornamenting her Garden.”

A French visitor reflected on the site of a

“small plantation, named Fitterasso..situated on a small eminence near the river. The site for the house, for none has hitherto been built, is the most pleasant spot which should be chosen in this flat, level country, where the tedious sameness of the woods is scarcely variegated by some houses, thinly scattered and where it is hardly possibly to meet with a pleasant landscape. His garden is separated from the River by a morass, neatly drained; the whole extent of the northern bank of the river is nearly of the same description. Dr. Baron intends to purchase the intervening space, and to convert it into meadow-ground. This alteration will improve the prospect, without rendering it a charming vista.”

A February 2, 1734 advertisement in the

South Carolina Gazette offered a house,

"on an island which commands an entire prospect of the Harbor.” The term prospect appears time and again in colonial references to gardens. A prospect was an extensive or commanding sight or view of vital importance in closing a site for a dwelling or garden in the eighteenth century. When describing William Middleton’s mount at Crowfield in 1743, Eliza Lucas Pinckney noted,

“upon it as a roman temple. On each side of this are other large fish ponds properly disposed which form a fine prospect of water from the house.”

On May 22, 1749, the house

“Belonging to Alexander Gordon…From the house Ashley and Cooper rivers are seen, and all around are vista’s and pleasant prospects” was advertised in the

South Carolina Gazette. Vistas were planned as intentional viewpoints for surveying pleasant aspects of the adjoining landscape in eighteenth century gardens and pleasure grounds up and down the Atlantic seacoast.

Sites and Sights - Mounts

Colonial gardeners often constructed artificial viewing sights to survey their gardens and the nearby countryside. These mounts usually consisted of a pile of earth heaped up to be used as the base for another structure such as a summerhouse or as an elevated site for surveying the adjoining landscape or as an elevated post for defensive reconnaissance or just a spot for fresh and cooling air in the summer. Occasionally gardeners planted their mounts with ornamental trees and shrubs. Mounts were often formed from the earth left from digging of cellars and foundations. Walks leading up the slope of a mount sometimes had their breadth contracted at the top by one half to add the illusion of greater length.

Eliza Lucas Pinckney described

Crowfield’s mount in 1743,

“to the bottom of this charming sport where is a large fish pond with a mount rising out of the middle--the top of which is level with the dwelling house and upon it is a roman temple.” Many gardeners constructed more than one mount on their grounds. An advertisement offered for sale "

a very large garden both for pleasure and profit, with a variety of pleasant walks, mounts, basons, canals” in the

South Carolina Gazette on January 30, 1749.

Mounts and bowling greens were components of English gardens long before the natural garden movement swept England in the eighteenth century. Colonials looked to traditional English garden design for their models as an ad in the 1739

South Carolina Gazette attests,

“To be sold a Plantation…on Ashley River, within three Miles of Charleston…the Gardens are extensive, pleasant and profitable, and abound with all sorts of Fruit trees, and resemble old England the most of any in the Province.”

Bowling Greens

The British American colonial bowling green evolved from a formal space dedicated to playing bowls to an open level green where people gathered for recreation and social affairs. Bowling greens were found in both public and private garden spaces and offered a smooth level turfed lawn which certainly could be used for playing bowls. Bowling greens could be circular or rectangular, those often measuring 100’ x 200’, and they were often sunken below the general level of the ground surrounding it. Eliza Lucas Pinckney noted that at

Crowfield,

“is a large square boleing green sunk a little below the level of the rest of the garden with a walk quite round composed of a double row of fine large flowering Laurel and Catalpas which form both shade and beauty.”

Sometimes called a square in late eighteenth and early nineteenth century America, the bowling green offered beauty and ornament as well as recreation. Bowling greens appeared early in South Carolina. A traveler noted on July 30, 1666, in Port Royal South Carolina,

“a plaine place before the great round house for their bowling recreation.” An ad in the

South Caroline Gazette on October 10, 1740 noted,

“TO BE LET…the house near Mrs. Trott’s Pasture, where the Bowling Green sits.”

Arbors and Bowers

South Carolina garden planners often trained plants into living arbors or bowers, which were open structures formed from trees, shrubs, or vines closely planted and twined together to be self-supporting or climbing up latticework frames. The size of eighteenth century arbors varied greatly. Arbors offered shade, privacy, or protection to many people such as gatherings of troops, picnickers, or worshipers or to a few people such as an arbor over as bench in a garden. Some colonials referred to a shaded alley or walkway as an arbor. On February 2, 1734, a landowner advertised in the

South Carolina Gazette property

“with shady Walks and Arbours, cool in the hottest seasons.”

English Style - Natural, Romantic

Certainly components and concepts of the natural English garden abounded in the South Carolina countryside as Eliza Lucas Pinckney noted in mid-century. Apparently she planter her fig orchard in something other than rigid rows. In April, 1742 she wrote,

“I have planted a large figg orchard…but was I to tell you…how to be laid out you would think me far gone in romance.” She also noted at Crowfield that

“From the back door is a spacious walk a thousand foot long; each side of which nearest the house is a grass plat enameled in a Serpenting manner with flowers.”

Another natural garden component was the use of vines trained to grow up wood and brick walls and columns of dwellings and outbuildings offering fruit, decoration, shade, bird food, and fragrance. In 1743 Pinckney noted that Middleton’s

"house stands a mile from, but in sight of the road…as you draw nearer new beauties discover themselves, first the fruitful Vine mantleing up the wall loaded with delicious Clusters.”

Despite the preponderance of traditional English garden components, South Carolinians attempted to adopt the new English garden designs which were more natural than geometric. Even so, a French traveler noted in 1796 that Middleton

“is esteemed the most beautiful house in this part of the country…The ensemble of these buildings calls to recollection the ancient English country seats…badly kept…the garden is beautiful, but kept in the same manner as the house.”

As late as 1806 emulation of English gardening concepts was a selling point as property changed hands in South Carolina. In the

Charleston Courier in 1806 an advertisement for a plantation for sale outside of Charleston noted

“the handsomest Garden in the state, and laid out when belonging to the late Mr. Williamson, by English Gardeners…and has since been much improved and additions made also by another English Gardener.”

South Carolina gardeners used the beauties of the natural countryside and adopted those European concepts that were both pleasing to the senses and practical to adorn the landscape they worked and played in daily. Whether these Carolina gardeners possessed a formal education and knew of Dutch, French, and English garden influences or knew nothing of classic design, most of them maintained their grounds as an art form, where they manipulated nature into their own unique concepts of order, utility, and beauty.

.jpg)