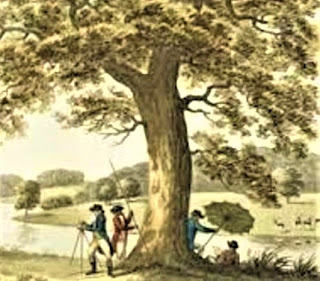

In the design of 18C pleasure grounds, a thicket is an intentionally planted or natural collection of small trees, dense underbrush, or shrubs growing thickly together, which are left in the landscape to add intrigue to the view and to attract singing birds. A thicket usually has tangles and vines protecting it from intrusion and providing a thermal cover for birds and small animals. Thickets are a little intimidating and a little joyful all at the same time.

In 1593, William Shakespeare wrote in 3 Henry VI, "Leave off to wonder why I drew you hither, into this cheefest Thicket of the Parke."

While John Milton wrote in in 1667, "How often from the steep Of echoing Hill or Thicket have we heard Celestial voices to the midnight air...singing."

In 1704, when Sarah Kemble Knight was traveling from Boston to New York on horseback, she was apprehensive when, "we rode on very deliberately a few paces, when we entered a thicket of trees and shrubs, and I perceived by the horse's going we were on the descent."

In 1743, Eliza Lucas Pinckney describing William Middleton's Crow-Field in South Carolina, wrote, "Next to that on the right hand is what immediately struck my rural taste, a thicket of young tall live oaks where a variety of Airry Chorristers pour forth their melody."

Traveler Peter (Pehr) Kalm described the area around Philadelphia in 1748 as containing “The common privet, or Ligustrum vulgare L., grows among the bushes in thickets and woods.”

When Manasseh Cutler visited Grey's Gardens in 1787 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, he noted, "We came into a spacious graveled walk, which directed its course further along the grove, which was tall wood interspersed with close thickets of different growth. As we advanced, we found our gravel walk dividing itself into numerous branches, leading into different parts of the grove.”

When Manasseh Cutler visited Grey's Gardens in 1787 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, he noted, "We came into a spacious graveled walk, which directed its course further along the grove, which was tall wood interspersed with close thickets of different growth. As we advanced, we found our gravel walk dividing itself into numerous branches, leading into different parts of the grove.”

Rochefoucauld-Liancourt noted on his 1796 visit to Drayton Hall in South Carolina, "The Garden here is better laid out…in order to have a fine garden, you have nothing to do but to let the trees standing here and there, or in clumps, to plant bushes in front of them, and arrange the trees according to their height. Dr. Drayton’s father…began to lay out the garden on this principle and his son…has pursued the same plan."

In planning the grounds around Monticello in 1804, Thomas Jefferson wrote, "The best way of forming the thicket will be to plant it in labyrinth spirally, putting the tallest plants in the centre and lowering gradation to the external termination, a temple or seat may be in the center then leaving space enough between the rows to walk and to trim up, replant the shrubs...and...This [grove] must be broken by clumps of thicket, as the open grounds of the English are broken by clumps of trees. plants for thickets are broom, calycanthus, altheas, gelder rose, magnolia glauca, azalea, fringe tree, dogwood, red bed, wild crab, kalmia, mezereon, euonymous, halesia, quamoclid, rhododendron, oleander, service tree, lilac, honeysuckle, brambles."

In planning the grounds around Monticello in 1804, Thomas Jefferson wrote, "The best way of forming the thicket will be to plant it in labyrinth spirally, putting the tallest plants in the centre and lowering gradation to the external termination, a temple or seat may be in the center then leaving space enough between the rows to walk and to trim up, replant the shrubs...and...This [grove] must be broken by clumps of thicket, as the open grounds of the English are broken by clumps of trees. plants for thickets are broom, calycanthus, altheas, gelder rose, magnolia glauca, azalea, fringe tree, dogwood, red bed, wild crab, kalmia, mezereon, euonymous, halesia, quamoclid, rhododendron, oleander, service tree, lilac, honeysuckle, brambles."

Jefferson was still contemplating the design of the landscape near his house, when he wrote in 1806, “The grounds which I destine to improve in the style of the English gardens are in a form very difficult to be managed...They are chiefly still in their native woods. which are majestic, and very generally a close undergrowth, which I have not suffered to be touched, knowing how much easier it is to cut away than to fill up. The upper third is chiefly open, but to the South is covered with a dense thicket of Scotch broom (Spartium scoparium Lin.) which being favorably spread before the sun will admit of advantageous arrangement for winter enjoyment...

“Let your ground be covered with trees of the loftiest stature. Trim up their bodies as high as the constitution & form of the tree will bear, but so as that their tops shall still unite & yield dense shade. A wood, so open below, will have nearly the appearance of open grounds. Then, when in the open ground you would plant a clump of trees, place a thicket of shrubs presenting a hemisphere the crown of which shall distinctly show itself under the branches of the trees. This may be effected by a due selection & arrangement of the shrubs, & will I think offer a group not much inferior to that of trees. The thickets may be varied too by making some of them of evergreens altogether, our red cedar made to grow in a bush, evergreen privet, pyrocanthus, Kalmia, Scotch broom. Holly would be elegant but it does not grow in my part of the country.

“Of prospect I have a rich profusion and offering itself at every point of the compass. Mountains distant & near, smooth & shaggy, single & in ridges, a little river hiding itself among the hills so as to shew in lagoons only, cultivated grounds under the eye and two small villages. To present a satiety of this is the principal difficulty. It may be successively offered, & in different portions through vistas, or which will be better, between thickets so disposed as to serve as vistas, with the advantage of shifting the scenes as you advance your way.”

Also in 1806. Bernard M’Mahon wrote in his The American Gardener’s Calendar, “First an open lawn of grass-ground is extended on one of the principal fronts of the mansion or main house, widening gradually from the house outward, having each side bounded by various plantations of trees, shrubs, and flowers, in clumps, thickets, &c. exhibited in a variety of rural forms, in moderate concave and convex curves, and projections, to prevent all appearance of a stiff uniformity...

“Thickets may be composed of all sorts of hardy deciduous trees planted close and promiscuously, and with various common shrubs interspersed between them, as underwood, to make them more or less close in different parts, as the designer may think proper. They may also be of ever-green trees, particularly of the pine and fir kinds, interspersed with various low-growing ever-green shrubs.”

In the introduction to his 1808 book The Country Seats of the United States, Englishman William Russell Birch (1755-1834), who hoped to promote "taste" in America for both architecture & landscape design, saw the result of the American balance of ornament and utility, and he tried to explain it this way: "The comforts and advantages of a Country Residence, after Domestic accomodations are consulted, consist more in the beauty of the situation, than in the massy magnitude of the edifice: the choice ornaments of Architecture are by no means intended to be disparaged, they are on the contrary, not simply desirable, but requisite. The man of taste will select his situation with skill, and add elegance and animation to the best choice. In the United States the face of nature is so variegated; Nature has been so sportive and the means so easy of acquiring positions fit to gratify the most refined and rural enjoyment, that labour and expenditure of Art is not so great as in Countries less favoured."