Many well-to-do homeowners intentionally chose their home sites on naturally sloping ground or on the bank of a river. They intended to plant level grassy (or more intricate) garden areas as part of a series of terraced falls or graduations with sloping turf fronts & sides. Often when the dwelling house was newly built, the earth, clay, & rubbish removed for cellars & foundations were used to shape the terraced falls. Hills were intentionally cut into slopes & flats where owners & guests could walk.

Visitors traveling on land would usually approach the formal entrance to a house by a flat carriage way. Guests asked to stay for a while, often would be invited to take a walk in the terraced garden on the opposite side of the home. People usually walked between these flat levels by means of grass ramps.

Each individual descent was referred to as a fall. Gentry owners showcased their genteel taste in gardening on these terraces, which served as their stage to those passing by or visiting.

Historically from Persia to Italy to England, terraces have provided a setting for the house, a pleasing view from upper story windows, a platform for surveying the surrounding countryside, and a grand stage for the owner. A contemporary American garden authority acknowledged the garden as a stage when he wrote, "regular terraces either on natural eminences or forced ground were often introduced...for the sake of prospect...one above another, on the side of some considerable rising ground in theatrical arrangement."

Such designs elevated the wealthy owner above the common audience passing by or strolling through. One look at nature so well ordered, and the observer could have no doubt that here lived a person destined to be in charge.

Falls appeared early in colonial Virginia, where Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spottswood (1676-1740) installed terraced gardens at the Governor's Palace in Williamsburg between 1715 & 1719. The legislature had authorized moneis for the palace and for its formal walled gardens in 1706.

When new Virginia Governor William Gooch (1681-1751) arrived in 1727, he wrote of a "handsome garden, an orchard full of fruit, and a very large park." The walled entrance courtyard was separated from the rear formal garden by brick walls. A gate to the east of the formal garden led to Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood's (1676-1740) "falling garden," a seried of three terraces descending to a ravine where Spotswood had a stream dammed to create a "fine canal."

Later Spotswood built a private estate near Germanna, where William Byrd II came to call in 1732, & reported, "the Garden...has...3 Terrace Walks that fall in Slopes, one below another."

Berkeley on the James River in Virginia

Berkeley on the James River in VirginiaSpotswood's falling garden at the Governor's Palace spawned a slew of Virginia imitators. In 1726, Benjamin Harrison IV and his wife Anne Carter built Berkeley on the James River. The house faces the river on top of a hill with 3 grand, descending terraces dropping to the river and Harrison's Landing.

Carter's Grove on the James River in Virginia

Carter's Grove on the James River in VirginiaIn the 1730s, Virginian Lewis Burwell constructed a rectangular garden, 200' wide with 3 terraces dropping 500' down to the James River at his plantation Kingsmill. In 1751, his cousin Carter Burwell borrowed that design for his Carter's Grove which still can be visited near Williamsburg.

19th-century Depiction of the terraced gardens at Carter's Grove

During the same decade, John Robinson, Speaker of the Virginia House of Burgesses, installed "a large falling garden enclosed with a good brick wall" at his home Pleasant Hall overlooking the Mattaponi River.

Some garden terraces proved treacherous. In the 1730s, Landon Carter built a falls garden at his home Sabine Hall on the north side of Virginia's Rappahannock River. Carter's garden consisted of 6 deep falls spanning the width of the house & dropping to the river below. The terraces were so steep, that he "almost...disjointed" his hip by "walking in the garden." In 1783, the elder Charles Carroll of Annapolis actually died as a result of a fall in his garden.

The same style garden also was appearing in more conservative New England as well. In 1736, Will Griff's contract to build Thomas Hancock's house & garden in Boston stated, "I...oblidge myself...to...layout the next garden or flatt from the Terras below." He also agreed to "order and Gravel the Walks & prepare and Sodd ye Terras adjoining with the Slope on the side."

Parnassas Hill home of Dr. Henry Stevenson painted by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) about 1769.

In Maryland, Irishman Dr. Henry Stevenson (1721-1814) built his home Parnassus Hill between 1763 & 1769, on the Jones Falls River north of Baltimore, where he & his brother, also a physician, actually made their money as wheat exporters. Dr. Henry Stephenson, who had come to Maryland in 1745, also pursured medicine pioneering a smallpox vaccine. In February of 1769, the Maryland Gazette noted, "Dr. Henry Stevenson devotes part of his mansion on 'Parnassus Hill' to the use of an Inoculating Hospital, and opens it to all who may apply." The hospital closed in 1777, as staunch loyalist Stevenson left Baltimore to serve in the British service as a surgeon in New York, returning to Baltimore in 1786, when Revolutionary tempers had cooled. The terraced gardens at the combination home & hospital were among the earliest in Baltimore.

Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) painting of William Paca with the naturalized area of his garden in the background.

Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) painting of William Paca with the naturalized area of his garden in the background.William Paca (1740-1799), a signer of the Declaration of Indpendence & a federal district court judge, was born in Harford County, Maryland, and educated in Philadelphia and London. In 1763, Paca ensured his social & economic position by marrying Mary Chew, the daughter of a wealthy Maryland family.

William Paca's falling, terraced garden in Annapolis.

William Paca's falling, terraced garden in Annapolis.Four days after their wedding, Paca purchased two lots in Annapolis and began building the five-part mansion plus an extensive pleasure garden. Paca planned a walled garden for his new home in the 1760s.

Paca Gardens in Annapolis, Maryland

Constructed between 1763-1765, the estate is known chiefly for its elegant falling gardens including 5 terraces, a fish-shaped pond, and a wilderness garden.

View from William Paca's house across his garden to the city of Annapolis.

View from William Paca's house across his garden to the city of Annapolis.The garden was to consist of 3 falls, narrowing as they dropped 16 1/2' to the lowest level of the garden. The terrace closest to the house measured 80' in width, the next 55', & the last 40'. This design allowed those viewing the 2 acre garden from the house to see grounds that appeared larger than reality, & those viewing from below to see a house that seemed grander than it was.

18th-century English image

Using "optics" to create an illusion of larger houses & grounds was particularly important in colonial towns, where space was limited, but the need to appear important was boundless.

View from the natural area of William Paca's garden up to the house.

View from the natural area of William Paca's garden up to the house.Another terraced garden in Marylnad belonged to Charles Carroll, the Barrister, 1723-1783, who had spent his youth in England receiving a classical education. He did not marry the 21 year old Margaret Tilghman 1743-1817, until he was 40 in 1763. By then, he was working on completing the house and grounds at his country seat near Baltimore. In 1756, Carroll had begun construction of his country house Mount Clare. A series of grass ramps led from the bowling green down shaded terraces or falls. A sweeping view spread across the lower fields to the waters of the Patapsco River, about one mile away.

The Garden Facade entrance at Mount Clare. Only the faintest definition of the bowling green and the terraces remain. During the Civil War the house served as quarters for Union soldiers. After 1865, the house was used as a German beer garden until 1890.

The gardens were popular with visitors. In 1770, Virginian Mary Ambler visited and recorded that she, "took a great deal of Pleasure in looking at the bowling Green & also at the...Very large Falling Garden there...the House...stands upon a very High Hill & has a fine view of Petapsico River You step out of the Door into the Bowlg Green from which the Garden Falls & when you stand on the Top of it there is such a Uniformity of Each side as the whole Plantn seems to be laid out like a Garden there is also a Handsome Court Yard on the other side of the House."

Margaret Tilghman Carroll (1743-1817) at the Garden Facade by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827)

When John Adams, in Baltimore for a session of the Continental Congress in February of 1777, spoke highly of Mount Clare. "There is a most beautiful walk from the house down to the water; there is a descent not far from the house; you have a fine garden then you descend a few steps and have another fine garden; you go down a few more and have another."

View of Mount Clare from the Terraced Lower Garden area by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827)

Because the land around the harbor at Baltimore was hilly as it dropped toward the bay, many builders chose terraced falling gardens for the south side of their homes. The terracing of gardens itself served both aesthetic & practical purposes in the colonial Mid-Atlantic. Pragmatic Mid-Atlantic landowners often constructed their terraces when the dwelling house was newly built; so that the earth, clay, and rubbish that come out of the cellars & foundations could be used to shape the falls.

On the same 1777 visit to Baltimore, John Adams noted in his diary, William Lux's Chatsworth, The seat is named Chatsworth, and an elegant one it is -- the large garden enclosed in lime and before the yard two fine rows of large cherry trees which lead out to the public road. There is a fine prospect about it. Mr. Lux lives like a prince. The grounds included an enclosed 164 ' by 234' terraced garden which fell toward the Baltimore harbor.

William Lux's Chatsworth in Baltimore, Maryland. By the time this map was drawn, Lux's estate had been sold and had become a public pleasure garden called Gray's Gardens. Map detail from Cartographer Charles Varle & Engraver Francis Shallus, Warner and Hann's "Plan of the City and Environs of Baltimore, Respectfully didecated to the Mayor, City Council & Citizens thereof by the Proprietors," 2nd edition (Baltimore, 1801; 1st 1799, drawn in 1797).

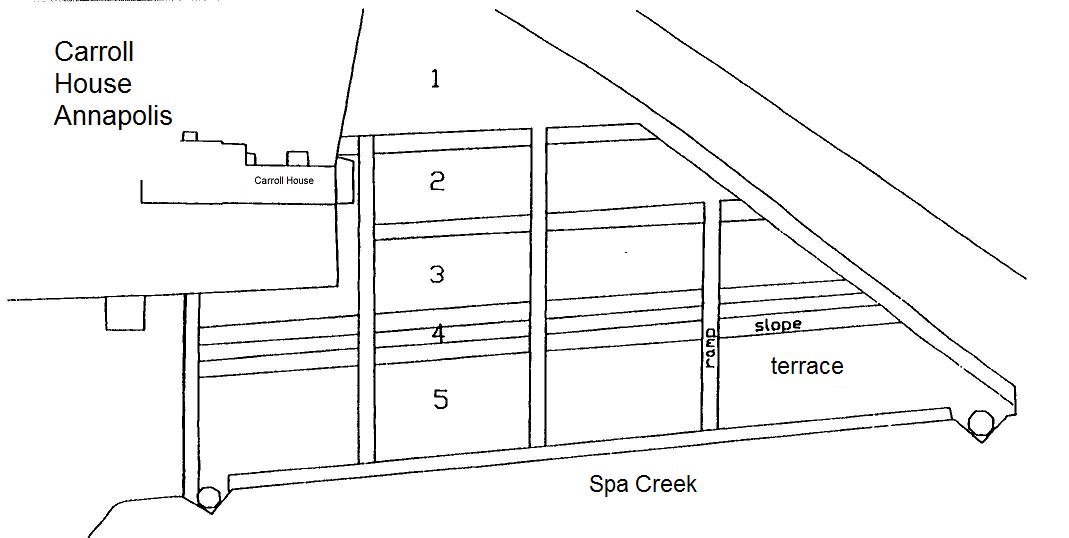

William Lux's Chatsworth in Baltimore, Maryland. By the time this map was drawn, Lux's estate had been sold and had become a public pleasure garden called Gray's Gardens. Map detail from Cartographer Charles Varle & Engraver Francis Shallus, Warner and Hann's "Plan of the City and Environs of Baltimore, Respectfully didecated to the Mayor, City Council & Citizens thereof by the Proprietors," 2nd edition (Baltimore, 1801; 1st 1799, drawn in 1797).On uneven hillsides, terraces created flat areas for planting & helped control erosion. In 1772, Charles Carroll of Annapolis (1702-1782) wrote to his son, Charles Carroll of Carrollton, who was improving his gardens which dropped to the bank of Spa Creek, “If you wish to make a continental slope from ye Gate to ye wash house, I apprehend the Quantity of Water in great Rains going ye way may prove convenient.” The elder Carroll was still fretting about those garden slopes in 1775, as he wrote his son again: “Examine the Gardiner strictly as to...Whether he is an expert at leveling, making grass plots & Bowling Greens, Slopes, & turfing them well.” Carroll was well aware that falls were functional devices which could divert water drainage & reduce soil erosion.

The Carroll family gardens in Annapolis covered about 2 3/4 acres. The Carrolls were the weathiest family in Maryland with hundreds of acres across the state, but their in-town space was limited. Broadening terraces fell 24' from the house to Spa Creek in Annapolis. The garden terrace closest to the water was 50' wide, the next ascending terrace 40' wide, & the terrace closest to the house measured 30' in width. This plan made the 3 story house seem even more imposing when viewed by visitors approaching from the water. The Carrolls planted the beds of the terraced gardens at their home in the capitol of Maryland with an eye toward practicality. Orderly squares filled with vegetables surrounded by low privet hedges decorated the flats of Carroll’s falls garden. Painter Charles Wilson Peale reported, "the Garden contains a variety of excellent fruit, and the flats are a kitchen garden.”

When New England schoolteacher, Philip Vickers Fithian visited Nomini Hall in Virginia, he recorded in 1773, "From the front yard of the Great House...is a curious Terrace covered finely with Green turf & about five foot high with a slope of eight feet, which appears exceedingly well to persons coming to the front of the house... This Terrace is produced along the Front of the House...before the Front-Doors is a broad flight of steps of the same Height & slope of the Terrace."

Back in New England on 1774, Elihu Ashley reported seeing the house of Massachusettes Loyalist Timothy Ruggles, where the "land descends the the South, and he designs to make three Squares one about four feet above the other, which will make a most agreable Graduation, and if ever finished will be the grandest thing in the Province of its kind." Unfortunately, in 1775, the Rev. Mr. Ruggles left Boston with British Troops heading to Nova Scotia, where he settled permanently. His estates, gardens & all, in Massachusettes were confiscated. When he fled, Ruggles left his daughter, Bathsheba behind in Massachusetts. In 1778, she was hung to death while pregnant for killing her husband Joshua Spooner & stuffing his body down a garden well. Turbulent times.

In the midst of the Revolution that drove Timothy Ruggles away, Virginia military Colonel George Braxton also had his garden on his mind & wrote in a letter home, "I agreed wth Alexander Oliver Gardener...to finish my falling Garden wth a Bolling Green." After the war was over, travelers began to tour the new confederation. Thomas Lee Shippen described Westover on the James River in Virginia in December of 1783, "...commanding a view of a prettily falling grass plat...about 300 by 100 yards in extent."

In July of the same year, Johann David Schoepf visited the garden of father & son botanists John & William & Bartram in Philadelphia, "The Bartram garden is situated on an extremely pleasant slope across the Schuykill." While the gardens of the Bartram's in Philadelphia did drop toward the water, they were not laid out as traditional falling terraces.

The Bartram garden near Philadelphia.

When the Revolution was won & before he became the nation's first President, George Washington retired to Mount Vernon, where he actively planned & maintained his gardens. In February of 1785, Washington noted in his diary, "Planted ...Brown Berries in the west square in the Second plat...next the Fall or slope."

By 1777, terraced falls were so admired along the Rappahannock River in Fredericksburg, Virginia, that 8 lots were offered for sale in the newspaper noting that 4 were already "well improved with a good falling Garden." A 1780 ad in the same paper touted "a good dwelling house with every conveniencey that a family can wish for...a falling garden." House-for-sale advertisements in Maryland also reported terraced gardens.

Map detail from Cartographer Charles Varle & Engraver Francis Shallus, Warner and Hann's "Plan of the City and Environs of Baltimore, Respectfully didecated to the Mayor, City Council & Citizens thereof by the Proprietors," 2nd edition (Baltimore, 1801; 1st 1799, drawn in 1797).

Map detail from Cartographer Charles Varle & Engraver Francis Shallus, Warner and Hann's "Plan of the City and Environs of Baltimore, Respectfully didecated to the Mayor, City Council & Citizens thereof by the Proprietors," 2nd edition (Baltimore, 1801; 1st 1799, drawn in 1797).Of the traditional four-bed gardens near Baltimore, 15 sat on terraced falls. Typical of these was merchant John Salmon’s home, which perched atop a Baltimore County hill adjoining the country seat of his fellow merchant, Robert Oliver (1757-1834). Oliver was an Irishman from Belfast who arrived in Baltimore in 1783, working there as a merchant until 1819. The neighbors’ homes had mirror-image four-bed terraced gardens descending in the direction of the bay. Also arriving in Baltimore in 1783, Salmon built a two-story home with a balcony & piazza facing south, overlooking his falling gardens commanding a view of the town, harbor, & harbor below. In 1794, John Salmon's Baltimore property contained, "The garden ground...is laid off in beautiful falls." And in January, 1802, a notice announced, "Public Auction...estate of...Richard Chew...1220 acres...situate in Anne-Arundel county, lying on the Chesapeake Bay...a large and elegant garden laid off with falls."

A Baltimore country seat probably more remarkable for its name than its falling gardens was

+Baltimore+Museum+of+Art..jpg) Chairback by John & Hugh Findley c 1804. View by Francis Guy 1760-1820. Garden Facade of Mount Deposit. Baltimore Country Seat of David Harris (1752-1809) Baltimore Museum of Art.

Chairback by John & Hugh Findley c 1804. View by Francis Guy 1760-1820. Garden Facade of Mount Deposit. Baltimore Country Seat of David Harris (1752-1809) Baltimore Museum of Art.Nearby in Baltimore sat Bolton, which George Grundy built immediately after he acquired the 30-acre property in 1793. Grundy planned his garden at Bolton to consist of 3 individually fenced rectangular turfed falls dropping south toward the harbor. These terraces were more than 3 times the width of the house, & initially the lowest rectangular terrace was planted in rows to serve as a kitchen garden. Gravel walks defined each terraced division, & a walkway ran from the house bisecting each terrace.

.+Bolton+From+the+South+Garden+Facade.+1800+Maryland+Historical+Society.+Baltimore.+Detail+from+the+road+down+to+the+Baltimore+harbor..jpg) Francis Guy (1760-1820). Bolton From the South Garden Facade. 1800 Maryland Historical Society. Baltimore. Detail from the road down to the Baltimore harbor.

Francis Guy (1760-1820). Bolton From the South Garden Facade. 1800 Maryland Historical Society. Baltimore. Detail from the road down to the Baltimore harbor.At the turn of the century, Grundy altered the lower garden to a semicircular bed surrounded by a white picket fence that projected from the fencing enclosing the rectangular terrace just above it. In the center of this semicircle was a large flowering tree or group of shrubs surrounded by a circular walkway. Outside of this walkway & within the picket fence were rectangular beds now planted with flowers instead of vegetables & herbs.

.++Bolton+From+the+South+Garden+Facade.+1800+Maryland+Historical+Society.+Baltimore..jpg) Francis Guy (1760-1820). Detail of Bolton From the South Garden Facade. 1800 Maryland Historical Society. Baltimore.

Francis Guy (1760-1820). Detail of Bolton From the South Garden Facade. 1800 Maryland Historical Society. Baltimore.The large flowering tree or group of shrubs in the middle of the lowest flat at Bolton may have been a living bower or arbor. Colonial Americans had for decades planted trees, shrubs, flowering beans & vines for cooling shade. A visitor reported in 1679, “We had nowhere seen so many vines together as we saw here, which had been planted for the purpose of shading the walks on the river side.” In 1787, at Grey’s Gardens near Philadelphia, Manasseh Cutler reported, “At every end, side, and corner, there were summer-houses, arbors covered with vines or flowers or shady bowers encircled with trees and flowering shrubs.”

.++Bolton+From+the+South+Garden+Facade.+1800+Maryland+Historical+Society.+Baltimore.+Detail+Vegetable+Garden.jpg) Francis Guy (1760-1820). Bolton From the South Garden Facade. 1800 Maryland Historical Society. Baltimore. Detail Vegetable Garden at the bottom of the falling terraces.

Francis Guy (1760-1820). Bolton From the South Garden Facade. 1800 Maryland Historical Society. Baltimore. Detail Vegetable Garden at the bottom of the falling terraces.It is possible that the unusual large circle of shrubs or trees in the midst of Bolton’s garden may have been similar to the one in Salem, North Carolina, where a visitor wrote, “into the garden…we saw…a curiosity…extremely beautiful. It was a large summer house formed of eight cedar trees planted in a circle, the tops whilst young were chained together in the center forming a cone. The immense branches were all cut, so that there was not a leaf, the outside is beautifully trimmed perfectly even & very thick within, were seats placed around and doors or openings were cut, through the branches, it had been planted 40 years.”

.+Bolton+From+the+South+Garden+Facade.+1800+Maryland+Historical+Society.+Baltimore.+Detail+Lower+Garden.jpg) Francis Guy (1760-1820). Bolton From the South Garden Facade. 1800 Maryland Historical Society. Baltimore. Detail Lower Garden with the unusual arbor in the center, surrounded by flowering beds.

Francis Guy (1760-1820). Bolton From the South Garden Facade. 1800 Maryland Historical Society. Baltimore. Detail Lower Garden with the unusual arbor in the center, surrounded by flowering beds.Terraced gardens continued to appear in the 19th century as settlers moved westward along the Ohio River. These terraced gardens from America's colonies & new republic were often reproduced in the late Victorian period throughout the United States.

Home on the Ohio River early 1800s

Colonial revival gardens usually were built with brick or stone stairways rather than grass ramps leading from one level to the next making walking a little safer. And, perhaps, 19th century gentry drank a little less spirits than their ancestors.

The gardens of the 1844 Lanier Mansion in Madison, Indiana on the Ohio River on the 1876 atlas

+about+1769..jpg)

.jpg)

+at+the+Garden+Facade+by+Charles+Willson+Peale+(1741-1827).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

;+Jean+Michel+Moreau+le+jeune+(After)++Emile+ou+de+l'Education,+volume+III,+page+98,+of+Rousseau's+'Oeuvres+compl%C3%A8tes'+(Brussels+Boubers,+1774)..jpg)

Beningborough Hall, North Yorkshire, England

Beningborough Hall, North Yorkshire, England

Beningbrough Hall & Gardens, Beningbrough, York, North Yorkshire, England

Beningbrough Hall & Gardens, Beningbrough, York, North Yorkshire, England Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia

Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia

Royal Horticultural Society Harlow Carr Botanical Gardens Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England

Royal Horticultural Society Harlow Carr Botanical Gardens Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England Lost Gardens of Heligan, South West, Cornwall, England

Lost Gardens of Heligan, South West, Cornwall, England

The Tool Gate at the Atlanta Botanical Gardens, Georgia

The Tool Gate at the Atlanta Botanical Gardens, Georgia

Royal Horticultural Society Harlow Carr Botanical Gardens Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England

Royal Horticultural Society Harlow Carr Botanical Gardens Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England Brighton Flea Market, Brighton, England

Brighton Flea Market, Brighton, England Calke Abbey, Ticknall, Derby, Derbyshire, England

Calke Abbey, Ticknall, Derby, Derbyshire, England

The Tool Shed in the Melon Yard at the Lost Gardens of Heligan, South West, Cornwall, England

The Tool Shed in the Melon Yard at the Lost Gardens of Heligan, South West, Cornwall, England Royal Horticultural Society Harlow Carr Botanical Gardens Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England

Royal Horticultural Society Harlow Carr Botanical Gardens Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, England

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, England

Yorkshire National Forest, England

Yorkshire National Forest, England