In this painting, household chairs and tables are carried outdoors. 1738 William Hogarth, (English artist, 1697-1764) The Hervey Converstion Piece - The Holland House Group

Traditionally the formal pleasure gardens of the British gentry, living in servant-laden households, had served as pleasure grounds for promenading, playing at games & sport, meditating, romancing, or entertaining. It is clear from English paintings, that even the gentry were using their household furniture outdoors.

In this portrait, the wife sits on a garden bench. 1763 Arthur Devis (English artist, 1712-1787) Francis Vincent, his Wife Mercy, and Daughter Ann, of Weddington Hall, Warwickshire. Detail

18th Century English Woodcut

18th Century English WoodcutBy mid-century, the up-to-date colonial gardener knew that the latest taste dictated placing seats & benches to emphasize a focal point in the garden; to terminate an impressive vista on the property; to view the garden or an impressive vista; or to catch a cooling breeze under trees or by the water.

As early as 1669, English garden writer John Worlidge had instructed his readers in Systema Agriculturae that proper garden seats should be placed "at the ends of your walks...that whilst you sit in them you will have the view of your garden."

Here the gentleman sits on a bench which is clearly placed at a focal point in his garden. 1749 Arthur Devis (English artist, 1712-1787) The Thomas Cave Family

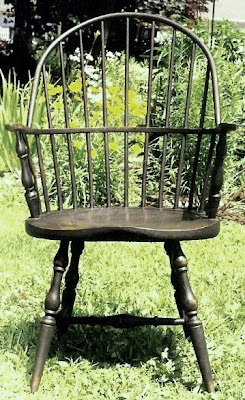

In his 1718 garden writings, Stephen Switzer, Iconographia Rustica or the Nobleman, Gentleman and Gardeners' Recreation makes a direct reference to the Windsor chair. By 1730, a London newspaper advertisement offered for sale "All sorts of Windsor Garden Chairs."

Like their less wealthy neighbors, colonial gentry usually carted common chairs outside, whenever the weather permitted. Gardens & yards served as welcome extensions of cramped indoor living spaces. Small, close living quarters were the rule in the colonies, even for the rich in the first decades of the 18th century, and this encouraged a variety of sedentary outdoor leisure activities across all classes such as doing chores, chatting, reading, gambling, & eating.

Like their less wealthy neighbors, colonial gentry usually carted common chairs outside, whenever the weather permitted. Gardens & yards served as welcome extensions of cramped indoor living spaces. Small, close living quarters were the rule in the colonies, even for the rich in the first decades of the 18th century, and this encouraged a variety of sedentary outdoor leisure activities across all classes such as doing chores, chatting, reading, gambling, & eating.Scenes from a Seminary for Young Ladies. St. Louis Art Museum.

Colonials needed something to sit on & something to put things on, indoors & out. Common household furniture including chairs, benches, & tables regularly found their way outdoors. Most British American colonials looked for some balance between the functional & the ornamental. The ordered, geometric gardens of the gentry in the colonies were a combination of ornament & function. Most colonists, even the wealthy Charles Carroll in Annapolis, grew edible plants in their formal terraced garden parterres.

Here the lady of the family sits in a Windsor type chair. 1749 Arthur Devis (English artist, 1712-1787) Mr and Mrs Van Harthals and Son

As the consumer revolution reached full-tilt mid-century, British American colonial gentry occasionally ordered special garden furniture from local craftsmen or from English factors. Garden furniture was part of the competitive furniture trade in England. Most furniture designers offered a few examples in their style books. Although Thomas Chippendale's furniture stylebook was the most influential of the period, enraver and London furniture designer Matthew Darly, who flourished between 1754 & 1778, seemed to have led the way toward this new design.

This tables & chairs sit far from the house in this painting. 1750 Arthur Devis (English artist, 1712-1787) Henry Fiennes Clinton, 9th Earl of Lincoln, with his wife Catherine and his son George on the great terrace at Oatlands

Always searching for the latest trend in the mid 1700s, British tastemakers were drawn to rustic or "forest" furniture style for their new natural gardens. No more of the stiff classic benches dotting those old-fashioned Dutch influenced William & Mary English formal gardens.

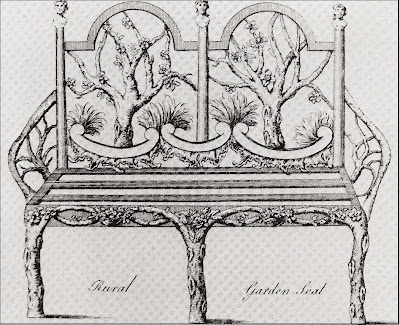

The 1761 3rd edition of Thomas Chippendale's The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director, contained a single plate called "Designs for Garden Seats," engraved by Matthew Darly, of rococo French chair with a possible rustic leg, a gothic French settee, and a "grotto chair." Matthew Darly was a London printseller, furniture designer, and engraver who owned a very successful print shop with his wife Mary.

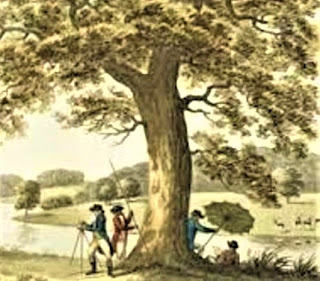

1773 Edward Smith (English artist) An Angling Party (perhaps The Willyams Family at Carnanton)

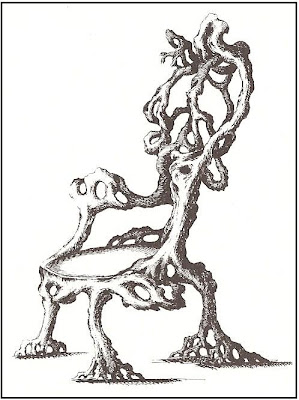

Even though English garden designers would soon be rebelling against the French and Dutch formal influence in the gardens of the gentry, Chippendale and Darly were introducing a fairly formal serpentine and rococo into the garden with these design patterns. Matthew (also called Mathias) Darly earlier had designed "root chairs and tables," whimsical garden furniture to be made out of gnarled roots, for Edwards and Darly, A New Book of Chinese Designs published in 1754.

In his 1765 design book The Cabinet and Chair-maker's Real Friend and Companion, English furniture designer Robert Manwaring described his garden seat designs, "designs given for rural Chairs for Summerhouses finely ornamented with Carvings, Fountains, and beautiful Landscapes, with the Shepherd and his flock, reaper, etc. Also, some very beautiful designs, supposed to be executed with Limbs of Yew, Apple, or Pear Trees, ornamented with Leaves and Blossoms, which if properly painted will appear like Native."

Manwaring's 1765 Rural Garden Seat design included classical busts as finials on the back posts. The basic Gothic design incorporated many of painter William Hogarth's serpentine curves. Hogarth had published a treatise on esthetics in 1753, The Analysis of Beauty, which promoted the serpentine curve as the true "line of beauty."

An 1735 inventory of Andrew Allen at Goose Creek, South Carolina did record "an Old Forest Chair." It is not clear whether this refers to one of the simple outdoor chairs which were known in England as forest chairs, or whether "forest" referred to the (beech) forests of the English the Chilterns where many of them were produced or to the shades of green in which they were painted.

There were also a few less practical "designer" forest garden chairs available in Britain.

One of Matthew Darly's root designs.

One of Matthew Darly's root designs.Life in the colonies was difficult, where many grew old & infirm quickly. For those who could not yet walk or no longer stroll & strut around their grounds, there was the "garden machine" or "rolling chair." A depiction of a "Garden Machine" appeared at the top of a trade card in late 18th century London, which also advertised "all Sorts of Yew Tree, Gothic, and Windsor Chairs."

In the last quarter of the century, two South Carolina inventories each boasted "1 Mahogany Roling Chair." Focusing on the special needs of the elderly and the infirm, Charleston cabinetmaker Thomas Elfe advertised in 1751, that he made "All kinds of Machine Chairs...for sickly or weak people."

1751 John Hesselius (1728-1778). The Grymes Children- Lucy Ludwell Grymes 1743-1830, Philip Ludwell Grymes 1746-1805, John Randolph Grymes 1747-96, & Charles Grimes 1748-? They were the children of Phillip Grymes and his wife Mary Randolph who were born at "Brandon" on the Rappahannock River in Middlesex County, Virginia. In the year following this painting, another daughter, Susanna Grymes was born into the family. Similar rolling chairs are found in British paintings.

1747 Arthur Devis (English artist, 1712-1787) Richard, Mary, and Peter, Children of Peter and Mary du Cane Detail

In 1752, a South Carolinian offered his plantation on the Ashley River for sale including "several handsome garden benches." Many garden seats appear in colonial inventories with no specific description, making identification of the style of garden furniture impossible.

Here both mother & father have Windsor chairs. 1751 Arthur Devis (English artist, 1712-1787) The James Family

Two 1755 Charleston inventories of record each of the deceased owning 2 "garden chairs." In 1767, Charleston turner John Biggard specifically advertised that he could produce both "Windsor and Garden chairs." The difference is not spelled out, and without a sketch, it is difficult to know the particularity of each.

Scenes from a Young Ladies Seminary. St. Louis Art Museum.

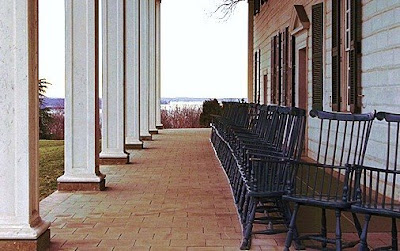

After the Revolution, gardening burgeoned into a democratic pursuit, needing to satisfy both the functional & the ornamental goals of the new nation. Lightweight, orderly, simple windsor chairs--that could be used indoors or out--seemed to fill the bill & appealed to all levels of society in the new republic. Sensible, airy Windsor chairs, painted or stained, became the most popular garden furniture in America.

Green windsor garden chairs had been popular in the South well before the Revolution. At first, merchants offered imported chairs to their stylish customers. In the 1764 Charleston inventory of John McQueen was "1 Windsor Garden Seat." In 1766, Charleston merchants Sneed & White offered "Windsor Chairs ... and settees ... walnut ... fit for piazzas or gardens," imported Philadelphia.

Aiming to cut out transportation costs & the middlemen, Philadelphia turner John Biggard moved to South Carolina in 1767, opening a "turner shop" advertising "Windsor and Garden chairs... cheaper than could be imported."

One 1775 Charleston inventory revealed 2 specialized windsors, "In the Passage...2 green Garden Windsor Chairs...2 Children do (garden Windsor Chairs)." Most inventories noted that the windsor chairs were painted green. The 1783 South Carolina inventory of Benjamin Cattell listed 12 green windsor chairs.

In this painting, the Windsor chairs are brought out to the statue in the garden. 1763 Johann Zoffany (German-born English painter, 1733-1810) The Mathew Family at Felix Hall, Kelvedon, Essex

A year later, inventory takers noted one dozen green windsor chairs in another Charleston entrance hall lined up like soldiers ready to see if their next engagement would be indoors or out. Charleston's leading professional gardener John Watson's 1789 inventory listed green windsor chairs in his seed sales room plus garden tools & books. On his piazza, he had 4 out of the ordinary teal benches & one normal green bench.

Outdoor windsors were often painted green to blend with nature. Englishman Uvedale Price wrote in his "Essays on the Picturesque" that white seats created unnatural spots in their green surroundings.

In this group portrait, the gentlemen have taken a variety of household furniture outdoors. 1780 Johann Zoffany (German-born English painter, 1733-1810) A Group of Gentlemen

Thomas Dobson's first American edition of his Encyclopedia or Dictionary of Arts and Science in Philadelphia in 1798, recommended, "To paint arbours and all kinds of garden work, give a layer of white ceruse grinded in oil of walnuts...then give two layers of green...This green is of great service in the country for doors, window shutters, arbours, gardens seats, rails either of wood or iron; and in short for all works exposed to the injuries of the weather."

Charleston wasn't the only city with a local supply of windsor chairs. In New York City, "a large and neat assortment of Windsor Chairs, made in the best and neatest manner, and well painted. Chairs and settees fit for piazza or garden."

Detail 1772 William Williams (1727-1791). The William Denning Family

Charleston wasn't the only city with a local supply of windsor chairs. In New York City, "a large and neat assortment of Windsor Chairs, made in the best and neatest manner, and well painted. Chairs and settees fit for piazza or garden."

Detail 1772 William Williams (1727-1791). The William Denning FamilyMarylander John H. Chandless advertised in the 1792, Baltimore Daily Repository "a large assortment of Windsor Chairs, of the newest fashions and painted in the best manner...Chairs, Settees, Garden Seats & Made and painted to particular directions." During the last decade of the 18C Baltimore furniture makers were arguably the best in the United States.

A rare surviving wooden bench is the late 18th century “Almodington Bench”, a diagonally slatted back design of yellow pine which was originally made for the Somerset County Maryland, plantation named “Almodington.” This is the oldest known piece of American garden furniture, which is now in the collection of the Museum of Southern Decorative Arts at Old Salem in Winston Salem, North Carolina.

1793 James Peale (1749-1831). The Ramsey-Polk Family in Cecil County, Maryland.

1793 James Peale (1749-1831). The Ramsey-Polk Family in Cecil County, Maryland.In the Virginia, inventories often listed "green chairs in the passage," meant to be used indoors & out. George Washington purchased 27 windsor side chairs for his piazza at Mount Vernon from Philadelphia Chairmakers Robert and Gilbert Gaw in 1796. The 1800 inventory of Mount Vernon recorded "in the Piazza...30 windsor Chairs."

Virginian John Randolph's Tagewell Hall included "5 green windsor chairs and one green settee belonging to my summer house." Mary Page of Spotsylvania County, Virginia ordered "one dozen Windsor Chairs for a passage."

In eastern North Carolina, David Stone's Hope Plantation contained 12 windsors in the hall passageway running from the front door to the back door, a design encouraging both air circulation & the moving of chairs in & out of doors.

Wooden chairs aged a little faster outdoors. In the Fayetteville North Carolina Minerva in 1796, Vosburgh & Childs advertised that they could make, paint, & repair Windsor chairs, probably the victims of a little rain and humidity now & again. Hall's North Carolina Wilmington Gazette on February 9, 1797, advertised "Windsor Chairs of every description...elegant settees of ten feet in length or under, suitable to either halls or piazzas...garden chairs suitable to arbors." A premature war between the North & the South was on as the ad noted, "those that are imported...are always unavoidably rubbed and bruised."

In this painting, the ladies sit on rather delicate chairs, while they gather around the pond to watch the gentlemen fish. 1770 Henry Benbridge (American colonial era artist, 1743-1812). The Tannatt Family

While in Wilmington, North Carolina, Eliza Clitherall recorded seats under trees in the more shady recesses of the Big Garden. William D. Martin recorded in his journal while visiting a "Girls Boarding School Pleasure Garden in Salem, North Carolina," Next I visited a flower garden...situated on a hill, ...At the bottom of this terrace were arranged circular seats, which, form the height of the hill in the rear were protected from the sun.

18th century English Woodcut.

18th century English Woodcut.In 1801, >Virginian Thomas Jefferson designed "benches for Porticos & Terraces...the back Chinese railing...to be painted green." Jefferson also noted "the seats at Washington by Lenox are 8 ft. long 21 I high, & the seat is 15 I broad, of five laths 2½ I wide." Peter Lenox (1771-1832) was the head carpenter, foreman, and clerk at the President's House in Washington, District of Columbia.

+Detail.+Rice+Hope+Taken+from+One+of+the+Rice+Fields.+South+Carolina.+2.jpg) c 1796. Charles Fraser (1782-1860) Detail of Settee on a Hill at Rice Hope Plantation Taken from One of the Rice Fields. South Carolina.

c 1796. Charles Fraser (1782-1860) Detail of Settee on a Hill at Rice Hope Plantation Taken from One of the Rice Fields. South Carolina.Not all gardeners relied on the simple windsor chair for their gardens. A grey garden bench appears in the 1771 Charles Wilson Peale painting of the Edward Lloyd family of Wye House in Talbot County, Maryland. The bench had rolled arms and a latticed back. Peale wrote in his autobiography that in Pennsylvania, "The proprietor [Peale himself] made summer houses (so called), roots to ward off the Sunbeams with seats of rest. One made of the Chinese taste, dedicated to meditation, with the following sentiments within it. "Mediate on the Creation of Worlds, which perform their evolutions in prescribed periods!"

1771 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) Edward Lloyd Family wife Elizabeth Tayloe and dau Anne.

1771 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) Edward Lloyd Family wife Elizabeth Tayloe and dau Anne. For those not satisfied with ordinary wood furniture, both English & local craftsmen also fashioned cast iron garden furniture including chairs, benches, & tables during the early federal period. Weight would have been a consideration in importing them from England. The Robert Wood foundry in Philadelphia produced cast iron garden furniture between 1804 -1858.

In this painting, the American grandmother is clearly sitting in a Windsor chair. 1787 Henry Benbridge (American artist, 1743-1812). The Hartley Family.

Henry Benbridge painted stone garden seats in paintings of a Charleston family; the Enoch Edwards family of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and the Taylor family of Norfolk, Virginia, during the last 2 decades of the 18C.

1779 Henry Benbridge (American artist, 1743-1812). The Enoch Edwards Family.

Whether these stone benches were real or fanciful is unclear. What is clear is that the dark green Windsor chair was the most enduring piece of garden furniture in practical 18th century America. The use of everyday chairs for garden events continued into the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Photo Maryland Historical Society

Photo Maryland Historical SocietyTo follow the development, diversification, & distribution of Windson Chairs see any of these books by Nancy Goyne Evans, (2005) Windsor-Chair Making in America: From Craft Shop to Consumer; (1997) American Windsor Furniture: Specialized Forms; and (1996) American Windsor Chairs.

+The+Hervey+Converstion+Piece+The+Holland+House+Group.jpg)

+Francis+Vincent,+his+Wife+Mercy,+and+Daughter+Ann,+of+Weddington+Hall,+Warwickshire.jpg)

+The+Thomas+Cave+Family.jpg)

.jpg)

+Mr+and+Mrs+Van+Harthals+and+Son.jpg)

+Henry+Fiennes+Clinton,9th+Earl+of+Lincoln,+with+his+wife+Catherine+and+his+son+George+on+the+great+terrace+at+Oatlands+(2).jpg)

+An+Angling+Party+(perhaps+The+Willyams+Family+at+Carnanton).jpg)

.+The+Grymes+Children-+Lucy+1743-1830,+Philip+1746-1805,+Jno+Randolph+1747-96,+Chas+1748-+.+Virginia+Historical+Society,+Richmond.jpg)

+Richard,+Mary,+and+Peter,+Children+of+Peter+and+Mary+du+Cane+Detail.jpg)

+The+James+Family.jpg)

.jpg)

+The+Mathew+Family+at+Felix+Hall,+Kelvedon,+Essex.jpg)

+A+Group+of+Gentlemen.jpg)

.+The+William+Denning+Family+vine+dog+urn+wall+chair.jpg)

.+The+Hartley+Family..jpg)

.+The+Enoch+Edwards+Family..jpg)