GARDEN STATUES

Surpisingly, garden statues appeared early in the

British American colonies and became even more popular in the early republic. Statues stood in the gardens of the gentry and later in the century at public pleasure gardens, where patrons from all levels of society could enjoy their beauty and symbolism. And occasionally, craftsmen and artisans embellished the grounds around their house with statues as well.

One of England's earliest garden commentators, Francis Bacon, took a dim view of garden statues. Francis Bacon, (1561-1626), English philosopher, statesman, scientist, lawyer, jurist, & author, wrote in his 1625

Essayes or Counsels, Civill and Morall in the essay entitled Of Gardens. His essay coincided with the new North American settlements along the Atlantic coast.

Bacon felt that statues added nothing to a real garden except, perhaps, pretense. He wrote,

"but it is nothing for great princes, that for the most part, taking advice with workmen, with no less cost set their things together, and sometimes add statues and such things, for state and magnificence, but nothing to the true pleasure of a Garden."

As early as 1718, Judge Sewall in Boston, Massachusettes, complained that,

"Quickly after the wind rose to a prodigious height...It blew down the southernmost of my cherubim's heads at the Street Gates." And three years later in 1721, he regretfully reported

, "Took down the northwardly cherubim's head, the other being blown down...I suppose ther have stood there near thirty years."

Around 1750, artist William Dering painted young George B

ooth in Virginia with statues flanking the young man and at the end of the walkway in the distance. Although these are certainly fanciful statues, it is not known if they were really in the landscape at that time. Unfortunately these details are from reproductions of these portraits, so visiting the museum is the only way to really evaluate each painting.

In 1754, New England preacher Ezra Stiles reported that Andrew and James Hamilton's Bush Hill in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania had a

"very elegant garden, in which are 7 statues in fine Italian marble curiously wrot." Perhaps curiously wrot is the key phrase, because a year later, when Daniel Fisher visited the same garden, he reported that

"It (did not) contain anything that was curious...a few very ordinary statues. A shady walk of high trees leading from the further end of the Garden looked well enough; but the G rass above knee high, thin and spoiling for the want of the Sythe."

rass above knee high, thin and spoiling for the want of the Sythe." In 1790, when Abigail Adams visited Bush Hill in Philadelphia, she noted,

"A beautiful grove behind the house, through which there is a spacious gravel walk, guarded by a number of marble statues, whose genealogy I have not yet studied." Charles Willson Peale painted these statues in his portrait of Mrs Robert Morris in the 1780s.

In 1760, William Williams portrayed Deborah Richmond in a garden with statues. An illustration of this painting is in the section of this blog describing garden alcoves.

Hannah Callender visited William Peters' garden at Belmont in 1762, near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She noted,

"On the right you enter a labyrinth of hedge of low cedar and spruce. In the middle stands a statue of Apollo. In the garden are statues of Diana, Fame and Mercury with urns."

Ar

ound 1767, John Singleton Copley painted a fountain statue in Rebecca Boylston's portrait. Copley was known to use English prints as models for his work. And in 1783, he painted John Adams with a garden statue as well.

By 1772, statues of Roman gods Venus, Apollo, and Bacchus graced John Custis' garden in Virginia. Nearby in 1774, while visiting John Tayloe's garden in Mount Airy, Virginia, a young schoolmaster reported,

"He has also a large well formed, beautiful Garden, as fine in every Respect as any I have seen in Virginia. In it stand four large beautiful Marble Statues."

Charle

s Willson Peale painted statues in several of his portraits. His 1770 portrait of John Beale Bordley and his 1772 painting of William Paca both pictured prominent statues

not mentioned elsewhere in period records.

While statues sat in the middle of green squares, or flanked garden walks or sat on garden gates, others found more exotic positions. In 1791, Reverand William Bentley visited the garden of Boston merchant Joseph Barrell.

"His garden is beyond any example I have soon. A young grove is growing in the background, in the middle of which is a pond, decorated with four ships at anchor, and a marble figure in the centre...The Squares are decorated with Marble figures as large as life." More modest statues began appearing in craftsmen's gardens as well. In 1795, in Annapolis, Maryland, silversmith William Faris noted,

"In the evening Cut the Sage by the Statue."

Garden statues produced by both Amerian and European artists became more widely available in the last years of the 18th century. In 1796, Philadelphia newspaper advertised,

"To be sold...Six elegant carved figures, the manufacture of an artist is this country, and made from materials of clay dug near the city, they are used for ornaments for gardens, or ballustrades, at the tops of houses or manels in the parlour, they are well burned and will stand any weather without being injured. and the represent Mars, and Minerva, Paris and Helen, A Male and Female Gardner."

By the end of the century, American gentry were coming up with ingenious places to place their ornamental statues. Many statues made it from

garden to housetop roof. Margaret and Gerard Briscoe placed full sized statues perched on marble pedestals at the end of each row of apple trees in their orchard at Clover Dale in Frederick County, Maryland. Artist Charles Peale Polk painted her proudly seated before a view of her orchard with statues in 1799.

In 1801, Timothy Dexter placed statues around the wall of his house as well as on its roof in Newburyport, Massachusettes.

Garden statues were gaining in visibility in the early republic as owners of public pleasure gardens began reflecting the ideals and heros of the new nation as icons in their gardens. In 1798, at the

Columbia Gardens in New York City, a visitor reported,

"I have been to...the Columbia gardens...placed all around were marble busts, beautiful figures of Diana, Cupid and Venus." And soon other garden owners followed suit. A newspaper advertisement for the

Mount Vernon Gardens in New York City boasted in 1800,

"lately imported from Europe...nineteen statues...Socrates, Cicero, Cleopatra, Shakespeare, Milton...the illustrious and immortal Washington...and miscellaneous figures from Greek mythology."

Five years later,

Vauxhall Gardens in New York City advertised,

"procured from Europe a choice selection of Statues and Busts, mostly from the first models of Antiquity, and worthy the attention of Amateurs...Washington, Cicero, Ajax, Antonious (in two poses, Hannibla, the Belvidere Apollo (in four sizes), Venus, Hebe (in two poses), Hamilton, Demostenes, Plenty, Hercules, Time, Ceres, Security, Modesty, Addison, Cleopatra (in two poses), Niobe, Pompey in two poses, Pope, The Medici Apollo, and Thalia."

The public settings of these gardens occasionally invited mischief. In the same year, in Charleston, South Carolina, the

Botanic Garden offered,

"One Hundred Dollars Reward. On Thursday Evening last, after sun-set, some evil minded person, taking advantage of the Gardener's absence, knocked at the Gate, and on being admitted treated the servant insolently for not admitting him sooner; he went directly to the Statue of Mercury, which was standing in the middle of the Garden, and threw it down, by which means it is entirely destroyed. The man was well dressed."

Maryland's Revolutionary War officer John Eager H

oward's home

Belvedere on a hill in Baltimore, was noted for its magnificent gardens graced with statues, much as the gardens at the papal Belvedere of Julius II boasted statues during the Italian Renaissance.

In 1802, Eliza Southgate visited

Hasket Derby in Salem, Massachusettes, and dramatically reported,

"From the lower gate you have a fine perspective view of the whole range, rising gradually until the sight is terminated by a hermitage...The hermitage...was scarcely perceptible at a distance; a large weeping willow swept the roof with its brances and bespoke the melancholy inhabitant. We caught a view of the little hut as we advanced thro' the opening of the trees; it was covered with bark; a small low door, slightly latched immediately opened at our touch; a venerable old man [stone statue] was seated in the center with a prayer book in one hand while the other supported his cheek, and rested on an old table which, like the hermit, seemed moulding to decay...a tattered coverlet was spread over a bed of straw...I left him impressed with veneration and fear which the mystery of his situation seemed to create."

.

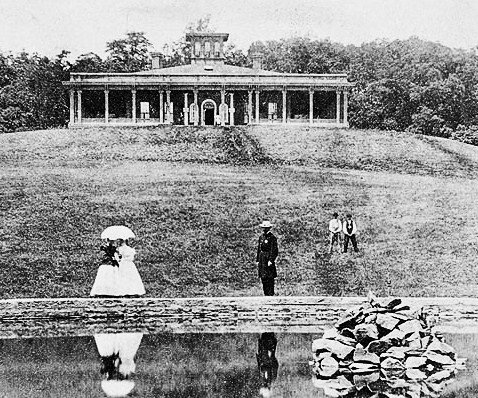

Baltimore Country Seat Druid Hill by Francis Guy

Baltimore Country Seat Druid Hill by Francis Guy Photo of Druid Hill Later in the 19th Century

Photo of Druid Hill Later in the 19th Century

not mentioned elsewhere in period records.

not mentioned elsewhere in period records.

's+Sundial,+Fredericksburg,+Virginia..jpg)