The growth of professional gardening trades in 18th century America spawned a need for apprentices to assist the craftsmen in their daily chores while training to become the professional gardeners of the future.

Apprentice gardeners were young boys sent to live away from home to learn the trade of gardener. They were usually placed by their parents or guardians or by the courts as orphans to serve under master or tradesmen gardeners for a given period.

Under such an arrangement, intended for the mutual benefit of both the gardener and the young student-laborer, the master contracted to supply instruction, & generally food & lodging, or a weekly sum as an equivalent to what those necessities would cost. The parents of the apprentice gardener would agree to that their charge would be of service to the master gardener his apprenticeship as their part of the contract.

The terms of apprenticeship was generally 3 years. But in America, it is apparent that boys as young as 8 were contracted out to gardeners, and they often served longer than 3 years. Custom and laws called for apprenticeship to end at the age when the attained "manhood."

In England, few could expect to attain to the rank either of master-gardener or tradesman, who had not served an apprenticeship to the one or the other. On the American side of the Atlantic, because the trade & gardens were generally less developed, advancement in the field of gardening was more open to those who never served an apprenticeship.

In Philadelphia, market or truck gardener Richard Collings, who kept a covered seed & plant stall at the Jersey Market, adverised in the 1770

Pennsylvania Gazette,

"Any person that has a boy that inclines to learn the art and mystery of a Gardiner, my apply." Market or truck gardeners & farmers grew produce to sell at the markets that supplied food for the growing populations of urban dwellers along the Atlantic coast in the 18th century. They grew culinary vegetables & fruits. Some grew only the more common hardy edibles for the kitchen, such as cabbage, pease, & turnips. Others supplied plants for propagation, such as cauliflowers, celery, & artichoke-plants, & pot-herbs, as mint and thyme. The most ambitious market growers grew items in hot-houses, & produced mushrooms, melons, pineapples, & other more exotic fruits over a longer growing season.

Young men who had apprenticed to other trades were sometimes called into garden service during the growing season. In Annapolis, craftsman William Faris used his clockmaking apprentice as garden help on several occasions.

In Maryland, several young boys were employed as apprentices by both professional gardeners & directly by owners of private gardens. In 1788, at age 8, William Lucas was bound out to Joseph Bignall, a professional gardener. Another 8-year-old, William Martin, was apprenticed to Jacob Eichelberger at his private residence in Baltimore County in 1786, to learn the art of gardening.

A lad named Cornelius Lary was bound out by his older sister at the age of 10, as a gardening apprentice to John Toon, who operated Toon’s Garden in Baltimore County. Toon’s Garden was one of several commercial pleasure gardens operating in the Baltimore area at the turn of the century. In the 1800-1801 Baltimore City directory, the 10-acre Toon’s Gardens was described as being

“situated about two miles down the [Patapsco] river…on an elevated situation,” & was said to

“command a view of the city & bay...During the summer months,” the directory recounted,

“a great concourse of citizens make excursions by land & water to these Gardens…with all kinds of refreshments.”

Andrew Smith was a Charleston, South Carolina, gardener in 1795, who advertised to train apprentices in the “art of gardening” in the March 12 edition of the

City Gazette and The Daily Advertiser,

"THE Subscriber has taken a lease of Widderburn Lodge, formerly called the Grove; he will take in apprentices for three years, to be instructed in the art of gardening and farming in general, to the best advantage; as great improvement will be made on the farm, in the garden, orchard, and in the common field, the sooner they were to enter to work the better. He does not wish any gentleman to send any negro unless of good principles, obedient to orders, and of a good genius. There is good accommodations on the farm for negros of every size and description. Andrew Smith."

Also in Charleston, South Carolina, gardener John Bryant, active in that city between 1795-1810, advertised for an apprentice to help him in 1796.

“An Apprentice is wanted to the above business, either white or colored. A Lad that is honest and industrious will meet with every encouragement.”

Occasionally gardeners advertised their need for apprentices through help-wanted notices in local newspapers. When the enterprising William Booth was establishing his nursery, he advertised, on March 2 1795, in the

Federal Intelligence & Baltimore Daily Gazette, that he was looking for one or two boys between the ages of 10 & 12 to serve as apprentice gardeners. As ad inducement, Booth noted that in several years such trainees would be capable of managing the gardens of gentlemen’s county seats around Baltimore, which, he declared, were

“going to ruin, for the want of a skillful gardener.”

Booth’s ad reflected the post-Revolutionary trends in professional gardening in the 18th-century Mid-Atlantic & South. White indentured & convict servants from the British Isles & black slaves had toiled side by side to design & maintain Mid-Atlantic & South gardens before the war with England.

After the Revolution, growing numbers of immigrant European, Caribbean, & British independent gardeners, assisted by white apprentices & free & slave blacks, took over the work. The American Revolution was the turning point in the development of independent gardening in the newly emerging capitalist nation, However, some aspects of Mid-Atlantic & South gardening did not change until the Civil War.

John Renauld was a gardener who immigrated from Rambouillet, France to Charleston some years after his birth in 1772. His only newspaper notice occurred in the

Charleston City Gazette and Daily Advertiser when he lost his young garden apprentice on July 7. 1806.

"Strayed, From the subscriber, a small new Negro Boy named JIM; about four feet 5 or 6 inches high; slender make and this vissage; has a scar on the right side of his face- above his eye; had on an oznaburgs shirt and blue cassimere trowsers. Whoever will deliver the said Boy at No. 34 Tradd-street, shall receive a reward of Five Dollars. JOHN RENAULD."

As visiting English agriculturalist Richard Parkinson pointed out about the Chesapeake and the South at the end of the 18th-century,

“where the livelihood is got out of the poor soil--it is pinched & screwed out of the negro.”

.jpg) Hampton Mansion, Entrance Facade, Towson, Maryland.

Hampton Mansion, Entrance Facade, Towson, Maryland. Hampton Mansion, Garden Facade, Towson, Maryland.

Hampton Mansion, Garden Facade, Towson, Maryland. Recently installed parterres at Hampton Mansion, Towson, Maryland.

Recently installed parterres at Hampton Mansion, Towson, Maryland.

.+Rebecca+Orne+(later+Mrs.+Joseph+Cabot).+Worcester+Museum+of++Art..jpg)

+pvt1st-gallery-art.com.jpg)

.+Girl+with+a+Squirrel..jpg)

Mount Clare Entrance Gates, Baltimore, Maryland.

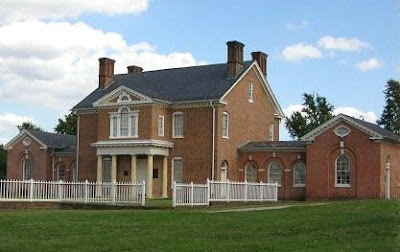

Mount Clare Entrance Gates, Baltimore, Maryland. Mount Clare Entrance Facade, Baltimore, Maryland.

Mount Clare Entrance Facade, Baltimore, Maryland. Mount Clare Garden Facade, Baltimore, Maryland.

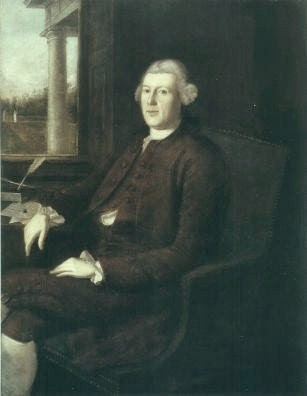

Mount Clare Garden Facade, Baltimore, Maryland. Charles Carroll the Barrister (1723-83) at the Entrance Facade by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827)

Charles Carroll the Barrister (1723-83) at the Entrance Facade by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) Margaret Tilghman Carroll (1743-1817) at the Garden Facade by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827)

Margaret Tilghman Carroll (1743-1817) at the Garden Facade by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) View of Mount Clare from the Lower Garden area by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827)

View of Mount Clare from the Lower Garden area by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) Young men who had apprenticed to other trades were sometimes called into garden service during the growing season. In Annapolis, craftsman William Faris used his clockmaking apprentice as garden help on several occasions.

Young men who had apprenticed to other trades were sometimes called into garden service during the growing season. In Annapolis, craftsman William Faris used his clockmaking apprentice as garden help on several occasions. A lad named Cornelius Lary was bound out by his older sister at the age of 10, as a gardening apprentice to John Toon, who operated Toon’s Garden in Baltimore County. Toon’s Garden was one of several commercial pleasure gardens operating in the Baltimore area at the turn of the century. In the 1800-1801 Baltimore City directory, the 10-acre Toon’s Gardens was described as being “situated about two miles down the [Patapsco] river…on an elevated situation,” & was said to “command a view of the city & bay...During the summer months,” the directory recounted, “a great concourse of citizens make excursions by land & water to these Gardens…with all kinds of refreshments.”

A lad named Cornelius Lary was bound out by his older sister at the age of 10, as a gardening apprentice to John Toon, who operated Toon’s Garden in Baltimore County. Toon’s Garden was one of several commercial pleasure gardens operating in the Baltimore area at the turn of the century. In the 1800-1801 Baltimore City directory, the 10-acre Toon’s Gardens was described as being “situated about two miles down the [Patapsco] river…on an elevated situation,” & was said to “command a view of the city & bay...During the summer months,” the directory recounted, “a great concourse of citizens make excursions by land & water to these Gardens…with all kinds of refreshments.” After the Revolution, growing numbers of immigrant European, Caribbean, & British independent gardeners, assisted by white apprentices & free & slave blacks, took over the work. The American Revolution was the turning point in the development of independent gardening in the newly emerging capitalist nation, However, some aspects of Mid-Atlantic & South gardening did not change until the Civil War.

After the Revolution, growing numbers of immigrant European, Caribbean, & British independent gardeners, assisted by white apprentices & free & slave blacks, took over the work. The American Revolution was the turning point in the development of independent gardening in the newly emerging capitalist nation, However, some aspects of Mid-Atlantic & South gardening did not change until the Civil War.