.

Benjamin K. Bliss–New York, New York

Benjamin K Bliss was born in Springfield, Massachusetts in 1819. He established a seed, bulb, and nursery firm in 1845, in New York City.

Information from the Smithsonian Institution Libraries and private research.

.

Sunday, March 29, 2020

Saturday, March 28, 2020

History Blooms at Monticello - Tennis Ball Lettuce

Tennis Ball Lettuce (Lactuca sativa cv.)

Tennis Ball was among Thomas Jefferson’s favorite lettuce varieties. He noted that “it does not require so much care and attention” as other types.

Tennis Ball was among Thomas Jefferson’s favorite lettuce varieties. He noted that “it does not require so much care and attention” as other types.

The parent of our modern Boston race of lettuces so popular today, this black-seeded variety was first sold by American seedsmen late in the 18th century. Tennis Ball is distinctive for its delicate, pale-green leaves, which form a loose head.

For more information & the possible availability for purchase

Friday, March 27, 2020

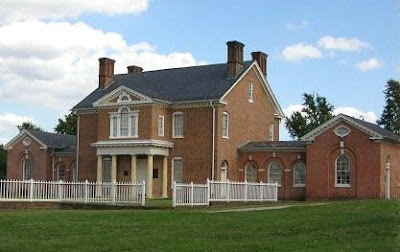

Garden Design - Hampton Mansion in Baltimore Country, Maryland

What is now called Hampton Mansion was built in Baltimore County, Maryland, between 1783 & 1790 by Colonel Charles Ridgely (1733-1790) and his wife Rebecca Dorsey (1739-1812) in the center of 1500 acres of land that Ridgely's father had purchased in 1695 from Henry Darnall, cousin of Lord Baltimore.

Its construction took seven years. The magnitude of the project and the length of time it took for it to be completed caused local residents to call the mansion Ridgely's Folly. With 25,000 square feet of living space, it was the largest private home in the U.S., when it was completed in 1790.

Construction of the house began in 1783, and Charles and Rebecca Ridgely began living there late in 1788; but the interior finishing work was not completed until 1790. When the house finally was finished, neighbors reported that Ridgely celebrated by inviting his friends over for a party that included wine, songs & card games; while his wife Rebecca celebrated by holding a prayer meeting in another part of the house. Charles and Rebecca had no children.

Captain Ridgely died 6 months after completing the house at age 56, and left his inheritance to his nephew, Charles Carnan (1760-1829), who took Ridgely as his last name as stipulated in the will. The nephew, a general in the state militia soon became known as General Ridgely and served as the Governor of Maryland between 1816 and 1819. Charles Carnan was married to Priscilla Hill Dorsey (1762-1814), who gave birth to 15 children.

Apparently the builder's widow Rebecca and his nephew Charles Carnan could not get along. To complicate matters further, Rebecca's much younger sister Priscilla was the wife of Carnan. Widow Rebecca wrote her sister,

Now to Acquaint you of some of my troubles, for they are many, in the first place I have given up to Charles Carnan, the Greatest part of my Estate and Now he treats me with the Greatest Disrespect and Slights, tho I have not put my self much in his power, which makes me Glad, tho I have given up all power over him, which make it a great time of trial to me, to be ill used by one I looked on as a Child.

The widow Rebecca left Hampton in 1791, and Charles Carnan Ridgely moved in.

Even before he became governor, General Ridgely was determined that Hampton and its grounds would be a showplace. It was said that, "He had the fortune that enabled him to live like a prince, and he also had the inclination." Ridgely decided to improve the grounds around the house. By 1802, he had formal parterre gardens set on terraced earthworks on the south garden side of the mansion; while on the north entrance facade, he created an English-style landscaped park.

English agricultural writer Richard Parkinson had lived near Baltimore in 1798-1800. He wrote about the area when he returned to England. He noted in his 1805 travel "sketches" that, "The General's lands are very well cultivated…his cattle, sheep, horses, etc., of a superior sort, and in much finer condition than many I saw in America. He is very famous for race horses and usually keeps three or four such horses in training, and what enables him to do this is that he owns very extensive iron works, or otherwise he could not."

At present-day Hampton, a national historical site, a curved approach to the entrance facade winds through level turfed ground, but Ridgely laid out the majority of Hampton’s gardens in a terraced design. Even the entrance facade probably had an avenue of trees, when the mansion was initially built. At the mansion’s garden façade, a turfed area 250 by 150 feet (alternately called the bowling green, the treat terrace, or the south lawn) crowned three additional terraced falls, connected by grass ramps, looking down toward Baltimore, ten miles to the south.

At Hampton & in most Maryland falls gardens, landowners chose to build simple turfed ramps, in place of the stairways familiar in European terraced gardens as well as in a few earlier Virginia falling gardens. Ridgely planned the Hampton’s first garden terrace to come 18 ' below the bowling green; the second dropped a further 6 '; & the third was 4 ' lower than the second. A grass walkway bisected the formal falling garden lengthwise from just below the bowling green to the kitchen garden at the base of their turfed terraces. Many Chesapeake gardeners planted fenced or walled kitchen gardens at the base of their ornamental terraces.

Hampton’s springhouse was similar to others dotting Baltimore’s hillsides. Springhouses, & the cold baths that sometimes accompanied them, needed a constant supply of cool water; the temperature of spring water at its source is normally in the mid-fifties Fahrenheit in the Mid-Atlantic. The cool water would circulate in channels beneath the brick or stone floor level of the well-ventilated building. Often there was little dry floor area, but the largest portion of area was devoted to the spring water channels, in which crocks were placed to cool. At Hampton’s springhouse, the fresh water spring emerged from under a decorative Gothic stone arch, circulated through the container channels, & left through an outlet purposefully made small, to discourage entry by unwanted animals.

The Falling Terraced Gardens at Hampton, Baltimore County, Maryland.

The Falling Terraced Gardens at Hampton, Baltimore County, Maryland.A second practical structure on Hampton’s grounds was the icehouse, located on the north side of the mansion. This particular icehouse was, however, more elaborate than most. Hampton’s ice vault was a turf-covered mound with a domed brick ceiling, fieldstone walls, & an underground vaulted passageway. The central cylindrical chamber was almost 34' deep. Ice, cut from nearby ponds in the winter, was packed in straw & stored for use during the heat of summer. Mid-Atlantic milk houses usually had a nearly supply of ice, which was used to harden butter as it was taken from the churn & worked on a slab of cold marble inside the milk house.

.jpg) Hampton Mansion, Entrance Facade, Towson, Maryland.

Hampton Mansion, Entrance Facade, Towson, Maryland. Hampton Mansion, Garden Facade, Towson, Maryland.

Hampton Mansion, Garden Facade, Towson, Maryland. Recently installed parterres at Hampton Mansion, Towson, Maryland.

Recently installed parterres at Hampton Mansion, Towson, Maryland.Thanks to Pat Reber for photos.

Thursday, March 26, 2020

Plants in Early American Gardens - China Rose Winter Radish

Radishes were regularly grown in the Monticello Kitchen Garden for use in salads. Introduced circa 1850, the China Rose Winter Radish is best when sown in late summer, then harvested after a light frost, and keeps well in cold storage.

In Field and Garden Vegetables of America (1865), Fearing Burr noted this radish to be “rather elongated…about five inches in length…skin comparatively fine, and of a bright rose-color; flesh firm, and rather piquant.”

For more information & the possible availability for purchase

Wednesday, March 25, 2020

Those Pesky Garden Squirrels as Emblems or Pets in Early America

.+Rebecca+Orne+(later+Mrs.+Joseph+Cabot).+Worcester+Museum+of++Art..jpg) 1757 Joseph Badger (1708-1765). Rebecca Orne (later Mrs. Joseph Cabot)

1757 Joseph Badger (1708-1765). Rebecca Orne (later Mrs. Joseph Cabot)+pvt1st-gallery-art.com.jpg) 1765 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Frances Deering Wentworth (Mrs. Theodore Atkinson, Jr.)

1765 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Frances Deering Wentworth (Mrs. Theodore Atkinson, Jr.) 1760s William Williams (1727-1791). Deborah Hall. Detail

1760s William Williams (1727-1791). Deborah Hall. Detail.+Girl+with+a+Squirrel..jpg) 1770 Attributed to Cosmo Alexander (1724-1772).

1770 Attributed to Cosmo Alexander (1724-1772). 1790 Denison Limner Probably Joseph Steward (1753-1822). Miss Denison of Stonington, Connecticut possibly Matilda.

1790 Denison Limner Probably Joseph Steward (1753-1822). Miss Denison of Stonington, Connecticut possibly Matilda. 1798 Ralph Earl(1751-1801). Elizabeth Eliot (Mrs. Gershom Burr)

1798 Ralph Earl(1751-1801). Elizabeth Eliot (Mrs. Gershom Burr)Besides being obsessed with squirrels attacking my bird-feeders at the moment, I am curious about animals appearing in paintings with 18th century Americans. Are they real? Or are they just an emblems symbolizing some quality trait of their owners?

About those squirrels. Reliable art historians Roland E. Fleischer, Ellen Miles, Deborah Chotner, & Julie Aronson suggest that these squirrels are not real. They are either copied from emblem books such as Emblems for the Improvement and Entertainment of Youth published in London in 1755, or from English prints. The latter theory is supported by the fact that some of the squirrels depicted in the paintings are composites of squirrels found in both America and England.

The 1755 emblem book describes the meaning of the emblem, "A Squirrel taking the Meat out of a Chestnut. Not without Trouble. An Emblem that Nothing that's worth having can be obtained without Trouble and Difficulty" All right, we all know that patience is a virtue, but is there more than meets the eye here, or perhaps less?

In the 19th century New American Cyclopaedia the squirrel is examined in detail. "The cat squirrel, the fox squirrel of the middle states, is...found chiefly in the middle states, rarely in southern New England; it is rather a slow climber, and of inactive habits; it becomes very fat in autumn, when its flesh is excellent, bringing in the New York market 3 times the price of that of the common gray squirrel...They are easily domesticated, and gentle in confinement, and are often kept as pets in wheel cages... The red or Hudson's bay squirrel...is less gentle and less easily tamed than the gray squirrel

Joseph Badger (1708-1765). Portrait of Two Children. 1760

Joseph Badger (1708-1765). Portrait of Two Children. 1760 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Boy (Henry Pelham) with a Squirrel. 1760

John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Boy (Henry Pelham) with a Squirrel. 1760 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Daniel Crommelin Verplanck with Squirrel 1771.

John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Daniel Crommelin Verplanck with Squirrel 1771.

Tuesday, March 24, 2020

History Blooms at Monticello - Asparagus Bean

Asparagus Bean (Vigna unguiculata sesquipedalis)

The Asparagus Bean, botanically similar to the black-eyed pea, is a Southern Asia native described by Linnaeus in 1763. First planted at Monticello in 1809, Jefferson wrote his son-in-law, John Wayles Eppes: “It is a very valuable [vegetable], much more tender and delicate than the snap [bean], and may be dressed in any form in which Asparagus may, particularly fried in batter, or chopped to the size of the garden pea, and dressed…in the French way.” Also called yardlong and Chinese long bean, this species is typically harvested when 12-15” but can also be used as a dried bean.

The Asparagus Bean, botanically similar to the black-eyed pea, is a Southern Asia native described by Linnaeus in 1763. First planted at Monticello in 1809, Jefferson wrote his son-in-law, John Wayles Eppes: “It is a very valuable [vegetable], much more tender and delicate than the snap [bean], and may be dressed in any form in which Asparagus may, particularly fried in batter, or chopped to the size of the garden pea, and dressed…in the French way.” Also called yardlong and Chinese long bean, this species is typically harvested when 12-15” but can also be used as a dried bean.

For more information & the possible availability for purchase

Monday, March 23, 2020

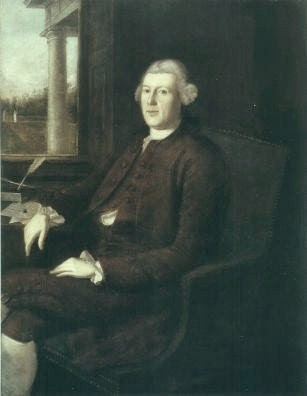

Historic Gardens - Mount Clare in Baltimore, Maryland Owned by Charles Carroll the Barrister

Although born the son of a surgeon in Annapolis, Charles Carroll 1723-1783 spent his youth in England receiving a classical education. He did not marry the 21 year old Margaret Tilghman 1743-1817, until he was 40 in 1763. By then, he was working on completing the house and grounds at his country seat near Baltimore.

In 1756, Carroll had begun construction of his summer house Mount Clare. Carroll had chosen to have the house built in the Georgian style of soft pink brick, laid in allheader bond, most of which would have been made on the plantation. A series of grass ramps led from the bowling green down shaded terraces or falls. A sweeping view spread across the lower fields to the waters of the Patapsco River, about one mile away.

The gardens were popular with visitors. In 1770, Virginian Mary Ambler visited and recorded that she, "took a great deal of Pleasure in looking at the bowling Green & also at the...Very large Falling Garden there...the House...stands upon a very High Hill & has a fine view of Petapsico River You step out of the Door into the Bowlg Green from which the Garden Falls & when you stand on the Top of it there is such a Uniformity of Each side as the whole Plantn seems to be laid out like a Garden there is also a Handsome Court Yard on the other side of the House."

When John Adams, in Baltimore for a session of the Continental Congress in February of 1777, spoke highly of Mount Clare. "There is a most beautiful walk from the house down to the water; there is a descent not far from the house; you have a fine garden then you descend a few steps and have another fine garden; you go down a few more and have another."

Mount Clare Entrance Gates, Baltimore, Maryland.

Mount Clare Entrance Gates, Baltimore, Maryland. Mount Clare Entrance Facade, Baltimore, Maryland.

Mount Clare Entrance Facade, Baltimore, Maryland. Mount Clare Garden Facade, Baltimore, Maryland.

Mount Clare Garden Facade, Baltimore, Maryland. Charles Carroll the Barrister (1723-83) at the Entrance Facade by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827)

Charles Carroll the Barrister (1723-83) at the Entrance Facade by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) Margaret Tilghman Carroll (1743-1817) at the Garden Facade by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827)

Margaret Tilghman Carroll (1743-1817) at the Garden Facade by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) View of Mount Clare from the Lower Garden area by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827)

View of Mount Clare from the Lower Garden area by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)