Kathy King tells us in her 2006 article in the Quarterly Archives of the Tredyffrin Easttown (Pennsylvania) Historical Society that "when flax, a bast—or plant—fiber that grows about a yard high, is processed & woven it becomes linen. Linen was not produced in 18C England, since the country was very protective of its woolen industry. In an attempt to help Ireland become more prosperous, the British government decided to promote linen production there & provided tax incentives, tariffs, & encouraged artisans from continental Europe with linen skills to immigrate to Ireland. There was plenty of cheap labor in Ireland for the onerous chore of flax preparation & spinning. Ireland became the capital of British fine linen manufacturing.

"To grow flax you plow the land twice, plant seeds close together so it grows tall with little branching, hand weed it, and, when ripe, pull it—cutting it will discolor it & keep the fiber from being as long. It is back-breaking work. Then you dry it, remove the seeds, & rett it—submerge it in a pond for a couple of weeks so it rots & the fibers separate. Then you dry it again, use a flax break to pound it to loosen the bark & connective tissue, & then scutch it—use a wooden sword-like tool to strike against the fiber to remove the bark & connective tissue. Next you hackle [there are many ways this was spelled at that time; I have used the modern spelling] it by repeatedly drawing it through a tool with many long, sharp metal teeth that rids the flax of short fibers—the tow—and bark. Then it is spun. It's harder to spin flax than wool, as it's long & wiry."

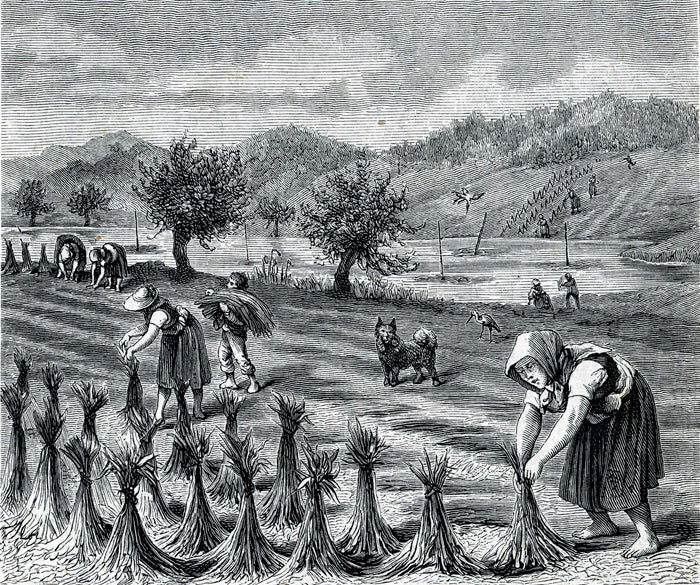

Step 1 - Pulling

Flax was sown in March or April. It was a fast growing plant that grew about 40 inches tall. Sometime during August, when the plants’ color turned to a golden hue, the plants were ready for harvest. In order to produce the best quality linen possible, the fiber had to be hand harvested by either pulling the whole plant by the root or by cutting the stalks very close to the ground.

Step 2 - Separating

After the harvest, flax seeds were removed through a process called “rippling”. During this process the plant stalks were pulled through a rippling comb, which was an iron or wooden device that was studded with nails for the easy removal of seeds and other undesirable plant elements.

Step 3 - Retting

To dissolve the pectin, which binds the plant fibers together, the remaining flax stalks had to be rotted or “retted”. This could be achieved periodically, to allow the dew to accomplish the rotting process. A faster way to decompose the pectin was to submerge the stalks deep into the local pond and weigh them down with heavy objects, such as stones or logs. With this method, the retting took just a few days.

Step 4 - Drying

In late August or early September, after the plants were retted and retrieved, the farmers tied them into small bundles and laid them out in the open fields to dry. This was done to bring the rotting process of the fibers to an end. Retting the flax stalks too long would render them brittle and unsuitable for textile production.

Step 5 - Roasting

When the weather was damp, it was often necessary to roast the flax in special ovens at very low temperatures until it was dry.

Step 6 - Breaking

After drying, the flax was ready for “scutching”, also called the “swinging” process. Small bundles of stalks were dragged in a swinging motion across a nail-spiked board to remove the woody parts of the fibers. At this time, only the long, soft flax strands remained, which were twisted into braids, ready to be spun. When the work was done, the young people of the village would meet for an evening of play and dance, the so-called “swing dances”.