By the 1760s, colonial British Americans were becoming restless with their limited choices in an expanding world. (And then, of course, there was that taxation problem.) Britain controlled what they could import & what they could manufacture. And, yet, they knew of the world beyond the limits imposed by the mother country.

Voltaire, although he had never been there, fancied China to be a diest philosopher's paradise. The colonials were banned from direct contact with goods from China by the British East India Company, but they could see Chinese designs in porcelain, textiles, wallpapers & pattern books and on trips abroad. They longed to show that they, too, had a larger view of an Enlightenment world filled with cross-cultural inspiration.

Books displaying Chinese designs, such as Matthais Lock & Henry Copland's 1752 New Book of Ornaments; Thomas Chippendale's 1754 Gentleman and Cabinet-maker's Director; William Chambers' 1757 Designs for Chinese Building, Furniture, Dresses, Machines, and Utensils; and Thomas Johnson's 1762 New Book of Ornaments, were widely circulated in the British American colonies. By 1774, the first American furniture book with Chinese designs appeared, The Carpenter's Rules of Work, in the Town of Boston.

From 1755-1758, London-trained indentured servant architect & carver William Buckland (1734-1774) was installing Chinese detailing in George Mason's home Gunston Hall at Mason Neck in Fairfax County, Virginia. Buckland & his chief carver, William Bernard Sears, were creating Chinese-style chairs for the house. Gunston Hall was filled with Chinese fretwork & moldings on the fireplace, doorways, & windows. Originally Buckland had been hired on a 4 year indenture to create a Chippendale parlor "in the Chinese taste" for George Mason's brother Thomson.

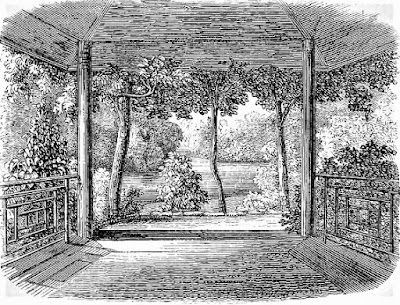

Hannah Callender wrote in her diary in 1762, of William Peters' Belmont near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, "We left the garden for a wood cut into vistas. In the midst is a Chinese temple for a summer house. One avenue gives a fine prospect of the city...Another avenue looks to the obelisk."

1772. William Paca of Annapolis painted by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827).

1772. William Paca of Annapolis painted by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Young Annapolis attorney William Paca (1740-1799) had traveled to England in 1761, to further his legal training abroad. Shortly after his return, he married wealthy Philadelphian Ann Mary Chew in 1763, & began to plan their Annapolis home & gardens, which he began building in 1765.

1772. Detail of Chinese Bridge in painting of William Paca by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827).

1772. Detail of Chinese Bridge in painting of William Paca by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827).William Buckland is credited with designing his garden, which was dominated by geometric terraces that fell to a small naturalized wilderness garden boasting a pond, a Chinese-style bridge, & a classical pavilion.

Chinese bridge in restored gardens at William Paca home in Annapolis, Maryland.

Chinese bridge in restored gardens at William Paca home in Annapolis, Maryland.In 1768, New York City's public pleasure garden Ranelagh offered a musical concert & fireworks featuring "Three Chinese Fountains, with Italian Candles, and a garandole."

Maryland newspaper advertisements offered fancy wooden paling constructed "emulating Chinese designs" for sale in the Chesapeake region by the late 1760s.

Mayor Samuel Powel (1738-1793) of Philadelphia redecorated his house after returning from 7-year-long Grand Tour of Europe in 1769. Young gentlemen of means often deferred the start of a career for the opportunity to broaden their knowledge & language skills on a Grand Tour. Among those he met on his continental travels were the Pope & Voltaire. Upon his return, Powel redesigned his garden & hung Chinese-style wallpaper in the parlor. Powel's cousin, financier Robert Morris (1734-1806) soon ordered Chinese wallpaper from Europe for his Philadelphia home.

Although he never built them, Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) looked to William Chamber's book, when he was contemplating building 2 Chinese pagoda garden pavilions at Monticello in Virginia in 1771.

Soon after the Treaty of Paris ended the war & ended the British East India Company's monopoly over the China trade in the colonies, America sent the vessel the Empress of China from the port in New York to China on George Washington's birthday in 1784.

Benjamin Franklin wrote in 1786, "the Chinese are an enlightened people, the most anciently civilized of any existing, and their arts are ancient, a presumption in their favour."

A former employee of the Dutch East India Company, who frequently traveled to China, settled in America in 1784, Andreas Everardu van Braam Houckgeest (1739-1801). He was known as van Braam. In 1796, he built "China's Retreat" at Croydon, near Philadelphia, featurning sliding windows & a cupola with Chinese fretwork balustrade.

Visitor Moreau de Saint Mery wrote that "the furniture, ornaments, everything at Mr. van Braam's reminds us of China. It is even impossible to avoid fancying ourselves in China while surrounded at once by living Chinese (servants) and by representations of their manners, their usages, their monuments, and their arts."

+%26+her+daughter+Francoise.+Rijksmuseum,+Amsterdam..jpg) Catharina van Braam (1746-1799) & her daughter Francoise. In van Braam's home hung a Chinese portrait of his wife & daughter clad in classical costumes & seated in a garden. But the garden was not Chinese. On a 1794 trip to Guangzhou, China, van Bramm commissioned the reverse glass painting, for which Chinese artists used engraved versions of paintings by, among others, the German painter Angelika Kaufmann (1741-1807). The subjects’ faces often were copied from miniatures; but for the rest, the paintings were direct imitations of European originals. The portrait of Catharina & Françoise is based on a 1773 Kaufmann painting of Lady Rushout & her daughter Anne, from a stipple engraving made by Thomas Burke (1749-1815) in 1784. Burke’s engraving apparently made its way to Guangzhou.

Catharina van Braam (1746-1799) & her daughter Francoise. In van Braam's home hung a Chinese portrait of his wife & daughter clad in classical costumes & seated in a garden. But the garden was not Chinese. On a 1794 trip to Guangzhou, China, van Bramm commissioned the reverse glass painting, for which Chinese artists used engraved versions of paintings by, among others, the German painter Angelika Kaufmann (1741-1807). The subjects’ faces often were copied from miniatures; but for the rest, the paintings were direct imitations of European originals. The portrait of Catharina & Françoise is based on a 1773 Kaufmann painting of Lady Rushout & her daughter Anne, from a stipple engraving made by Thomas Burke (1749-1815) in 1784. Burke’s engraving apparently made its way to Guangzhou.After only 2 years of living at his Philadelphia new mansion, van Braam sold it to a Captain Walter Sims in 1798. Captain Sims was also enamored of Chinese culture & ornament; so he, too, enjoyed the exotic atmosphere of the mansion. His only change was to rename it "China Hall."

In 1798, a newspaper advertisement offering for sale a small plot of land in New York City noted that, "A Chinese Temple, placed on one or two inviting spots, would render the appearance at once romantic and delightful." These depictions of Chinese gardens during the period give a glimpse into the inspiration for Chinese designs in colonial America & the new republic.

Engravings of the Yuan Ming-Yuan Summer Palaces and Gardens of the Chinese Emperor Ch'ien Lung. by Giuseppe Castiglione. (Published 1786) Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766) was an Italian Jesuit brother serving in China as a painter at the court of the Emperor. Castiglione was sent there as a missionary, arriving in China in 1715, and remaining until his death in 1766. As a youth, Castiglione learned to paint from Carlo Cornara & Andrea Pozzo, a member of the Society of Jesus at Trento. In 1707, at the age of 19, Castiglione formally entered the Society and traveled to Genoa for further training. By this time, his skill as a painter was recognized, & he was invited to do wall paintings at Jesuit churches. At the age of 27, he received instructions to go to China, completing wall paintings in Jesuit churches in Portugal & Macao along the way.

While in China, Castiglione took the name Lang Shining. In addition to his court duties, he was also in charge of designing the Western-Style Palaces in the imperial gardens of the Old Summer Palace. He practiced his art & his religion as court painter to 3 Emperors during the last Chinese Quing dynasty for 51 years. He introduced the ideas from his Italian Renaissance training of perspective, anatomical accuracy, and depicting 3 dimensional objects by using light & shade to Chinese art. He also absorbed Chinese artistic techniques into his own works.

Xushuilou+dongmian,+east+fa%C3%A7ade+of+Reservoir.jpg) Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766). 1786 Xushuilou dongmian, east façade of Reservoir.

Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766). 1786 Xushuilou dongmian, east façade of Reservoir.Xieqiqu+beimian,+north+fa%C3%A7ade+of+Palace+of+the+Delights+of+Harmony.jpg) Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766). 1786 Xieqiqu beimian, north façade of Palace of the Delights of Harmony.

Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766). 1786 Xieqiqu beimian, north façade of Palace of the Delights of Harmony.

Xianfashanmen+zhengmian,+fa%C3%A7ade+of+gate+leading+to+Hill+of+Perspective.jpg)

Wanhuazhen+huayuan,+the+Maze.jpg)

Haiyantang+dongmian,+east+fa%C3%A7ade+of+Palace+of+Calm+Seas.jpg)

Dashuifa+nanmian,+Great+Waters,+south+side.jpg)

.++An+Overseer+Doing+His+Duty,+sketched+from+life+near+Fredericksburg,+13+March+1798.jpg)

Terre cotta rhubarb pots at Knightshayes Garden, Tiverton, Devon, England

Terre cotta rhubarb pots at Knightshayes Garden, Tiverton, Devon, England Barnsdale Gardens, Exton, Oakham, Rutland, England.

Barnsdale Gardens, Exton, Oakham, Rutland, England.

Audley End Kitchen Garden, English Heritage, Essex, England

Audley End Kitchen Garden, English Heritage, Essex, England

..jpg)