Friday, December 14, 2018

History Blooms at Monticello

Peggy Cornett, who is Curator of Plants at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello in Virginia, tells us that -

The male and female Ginkgoes at Monticello are showing their golden fall color. In 1806, William Hamilton wrote to Thomas Jefferson that he intended to send him three trees that he thought Jefferson would "deem valuable additions" to his garden. Ginkgo biloba or the China Maidenhair tree was one of the three. Hamilton went on to say that it produced a "good eatable nut." The Gingko is a large, hardy, deciduous tree with delicate, fan-shaped leaves that turn bright yellow in fall, and it has been used medicinally for thousands of years. The female trees produce edible fruit, which many find malodorous.

For more information & the possible availability for purchase

Contact The Tho Jefferson Center for Historic Plants or The Shop at Monticello

Thursday, December 13, 2018

Gardeners - Wanted

Landowners Looking for Gardeners in the Mid-Atlantic & South

By the middle of the 18th century, both gardeners searching for employment & gentlemen looking for gardeners began placing ads in local newspapers in hopes of finding one another.

Even though independent gardeners appeared in South Carolina looking for work in the early 1730s, apparently there were not enough to meet the demand. In July, 1736, Robert Hume, a Charleston attorney, advertised in the South Carolina Gazette for an overseer “that understands Gardening to live at his Plantation near Charlestown.”

Robert Hume had been born in London and married Sophia Wiggington (1702-1774) in 1721, at St. Phillip's Church in Charleston. In 1726, Hume had bought 174 acres of Magnolia Umbra, north of "Exmouth lying East of the Broad Path," to which he added 110 acres; and the property became his residence and country seat. Robert died just a year after looking for an independent gardener for his property in Goose Creek Parish.

In Philadelphia in 1758, a gentry garden fancier placed an ad in the Pennsylvania Gazette. "Wanted for a Gentleman's Seat in the Country, a Person who understands Gardening." The gardener would have to be well recommended and would work on a yearly basis.

In the same newspaper in 1760, John Mifflin, a Pennsylvania plantation owner, was searching for a man "with a small Family who understands Gardening and Plantation Work."

During this period notices appeared in the South Carolina Gazette searching for gardeners. On March 16, 1765, “A GARDENER, who understands laying out and executing work in the- present taste, and skilful in a Kitchen-Garden” could hear of a good place by applying to the printer of the Gazette.

In April 1765, professional gardener & marketman Christopher Gadsden advertised for an assistant in the local newspaper, “Person that understands the managing of a garden and orchard (particularly a kitchen garden) and is willing to tend the markets constantly,” and in that June, he continued to search for a gardener “that understands the management of a garden, orchard, marketing” was would be offered “employment on a pleasant place within two miles of Charles-Town.”

John McPherson of Mount Pleasant in Pennsylvania, advertised for a gardener in 1766. McPherson was looking for a single man of "proper Resolution, Discretion, and Humanity, to command several other Servants under him."

Several gardeners worked at four shillings per day in the mid 1700s in the Annapolis & Eastern Shore gardens of Edward Lloyd IV. One of these gardeners (with a highly improbable name), James Lilleycrap, worked as a contract gardener at the Lloyds’ Annapolis garden on a daily basis during 1778 & 1779. In February 1780, he contracted to work for a full year at 300 pounds.

Apparently Lilleycrap was a trained gardener hired to undertake major garden redesign & installation. He probably employed others to assist him & paid them out of the 300 pounds. Lilleycrap’s arrangement illustrates just one of the new approaches to pleasure gardening in Maryland after the Revolution.

In 1772, another Pennsylvania gentleman, who knew what he wanted, advertised for "A Gardiner, Who understands his Business very well, and no other need apply." A similar ad appeared in 1773, appealing for " Single Man...willing to work on a Plantation (principally in a Garden)."

Robert Kennedy in Philadelphia, placed an extremely specific ad in 1775. "Wanted, On a pleasant well situated Farm, not many miles fro this city, A Middle aged Man and his Wife, the man to understand gardening and plantation work, the woman to be compleat at dairy business and house work." In the same year, another gentleman was searching for a "Gardener and his Wife, To take Care of a Gentleman's Country Seat, about four Miles from the City."

Apparently, the position with Robert Kennedy did not work out, for the Pennsylvania Gazette contained an ad in 1776, from a gardener and his spouse seeking a place for a "Gardener or Overseer of a Farm, a Person who can be well recommended; he has a Wife, who can cook and manage a Dariy."

In the summer of 1776, Frederick Hailer in Arch Street in Philadelphia advertised for a gardener. And in 1781, the French Consul in Arch Street was looking for a gardener "to work and manage a Garden a little Way out of Town."

When independent white gardeners started proliferating after the Revolution, they hired out by the day, month, or year. Visiting English agriculturalist Richard Parkinson reported that he hired a white man in Baltimore in 1799, to mow at “a dollar a day, with meat & a pint of whisky.”

He also recorded the costs of labor of various agricultural & gardening tasks at different seasons of the year around 1800 near Baltimore. In Baltimore, the town market supplied the produce needs of most of the citizens. Richardson recorded that for this market stall work, “Bartering in town costs one dollar & a half per day; at harvest-work, one dollar per day & a pint of whiskey.”

After the Revolution, gentlemen seldom sent to England for their gardeners but began to place advertisements for professional gardeners in local newspapers. Just north of Baltimore, Harry Dorsey Gough advertised in 1788, “I want to employ a complete gardener at Perry Hall…to undertake the management of a spacious, elegant Garden & Orchard.” A similar Baltimore notice in 1795, pleaded for a gardener who was specifically adept at managing strictly ornamental flower gardens.

In Richmond, Virginia, Adam Hunter placed a notice in the local paper searching for a “Complete Gardener, with or without a family (the latter would be preferred)” for his land near Fredericksburg in Stafford County.

After the Revolution, white gardeners working in port towns such as Philadelphia, Annapolis, & Baltimore, were as likely to be European as they were to be British. Europeans were favored by some hiring gentry in the postwar years. One gentleman searching for a gardener in Baltimore in the 1790s wrote, “A Dutch or Frenchman speaking English would be preferred.”

In 1782, Robert Monckton Malcolm of Monckton Park, between Neshaminy Ferry and Bristol, on the river, placed an ad in the Pennsylvania Gazette, "Wanted to Hire, Two German young or middle aged single Men, who understand farming, clearing and fencing of land; it will be necessary that one of them understands gardening."

In Prince George's County, Maryland, Rosalie Stier Calvert sought help planning her garden and grounds, and employed Philadelphia artist William Russell Birch in 1805, to draw up a landscape plan for Riversdale. She wrote that he was “busy making plans for the grounds of the house. I think he is very good at it and he is doing them with an eye to economy.”

Her father wasn't so sure she should take Birch's recommendations without a second opinion--his-- and wrote back, “glad to learn that you are using the architect Birch. You must not concern yourself about the cost of the plans. Copy them and send them to me. I’ll give you my observations.”

Occasionally foreign-born gardeners speaking little or no English contracted to work in gardens in the new republic confused their hopeful employers. In October 1816, Rosalie Calvert wrote her sister, “We have a German who seems to be knowledgeable and this greatly relieves me. One small inconvenience, however, is that he doesn’t understand a single word of English.”

By March 1819, the frustrated Rosalie wrote her father, “I recently discharged my German gardener...He knew nothing at all and couldn’t tell a carrot from a turnip.”.

By the middle of the 18th century, both gardeners searching for employment & gentlemen looking for gardeners began placing ads in local newspapers in hopes of finding one another.

Even though independent gardeners appeared in South Carolina looking for work in the early 1730s, apparently there were not enough to meet the demand. In July, 1736, Robert Hume, a Charleston attorney, advertised in the South Carolina Gazette for an overseer “that understands Gardening to live at his Plantation near Charlestown.”

Robert Hume had been born in London and married Sophia Wiggington (1702-1774) in 1721, at St. Phillip's Church in Charleston. In 1726, Hume had bought 174 acres of Magnolia Umbra, north of "Exmouth lying East of the Broad Path," to which he added 110 acres; and the property became his residence and country seat. Robert died just a year after looking for an independent gardener for his property in Goose Creek Parish.

In Philadelphia in 1758, a gentry garden fancier placed an ad in the Pennsylvania Gazette. "Wanted for a Gentleman's Seat in the Country, a Person who understands Gardening." The gardener would have to be well recommended and would work on a yearly basis.

In the same newspaper in 1760, John Mifflin, a Pennsylvania plantation owner, was searching for a man "with a small Family who understands Gardening and Plantation Work."

During this period notices appeared in the South Carolina Gazette searching for gardeners. On March 16, 1765, “A GARDENER, who understands laying out and executing work in the- present taste, and skilful in a Kitchen-Garden” could hear of a good place by applying to the printer of the Gazette.

In April 1765, professional gardener & marketman Christopher Gadsden advertised for an assistant in the local newspaper, “Person that understands the managing of a garden and orchard (particularly a kitchen garden) and is willing to tend the markets constantly,” and in that June, he continued to search for a gardener “that understands the management of a garden, orchard, marketing” was would be offered “employment on a pleasant place within two miles of Charles-Town.”

John McPherson of Mount Pleasant in Pennsylvania, advertised for a gardener in 1766. McPherson was looking for a single man of "proper Resolution, Discretion, and Humanity, to command several other Servants under him."

Several gardeners worked at four shillings per day in the mid 1700s in the Annapolis & Eastern Shore gardens of Edward Lloyd IV. One of these gardeners (with a highly improbable name), James Lilleycrap, worked as a contract gardener at the Lloyds’ Annapolis garden on a daily basis during 1778 & 1779. In February 1780, he contracted to work for a full year at 300 pounds.

Apparently Lilleycrap was a trained gardener hired to undertake major garden redesign & installation. He probably employed others to assist him & paid them out of the 300 pounds. Lilleycrap’s arrangement illustrates just one of the new approaches to pleasure gardening in Maryland after the Revolution.

In 1772, another Pennsylvania gentleman, who knew what he wanted, advertised for "A Gardiner, Who understands his Business very well, and no other need apply." A similar ad appeared in 1773, appealing for " Single Man...willing to work on a Plantation (principally in a Garden)."

Robert Kennedy in Philadelphia, placed an extremely specific ad in 1775. "Wanted, On a pleasant well situated Farm, not many miles fro this city, A Middle aged Man and his Wife, the man to understand gardening and plantation work, the woman to be compleat at dairy business and house work." In the same year, another gentleman was searching for a "Gardener and his Wife, To take Care of a Gentleman's Country Seat, about four Miles from the City."

Apparently, the position with Robert Kennedy did not work out, for the Pennsylvania Gazette contained an ad in 1776, from a gardener and his spouse seeking a place for a "Gardener or Overseer of a Farm, a Person who can be well recommended; he has a Wife, who can cook and manage a Dariy."

In the summer of 1776, Frederick Hailer in Arch Street in Philadelphia advertised for a gardener. And in 1781, the French Consul in Arch Street was looking for a gardener "to work and manage a Garden a little Way out of Town."

When independent white gardeners started proliferating after the Revolution, they hired out by the day, month, or year. Visiting English agriculturalist Richard Parkinson reported that he hired a white man in Baltimore in 1799, to mow at “a dollar a day, with meat & a pint of whisky.”

He also recorded the costs of labor of various agricultural & gardening tasks at different seasons of the year around 1800 near Baltimore. In Baltimore, the town market supplied the produce needs of most of the citizens. Richardson recorded that for this market stall work, “Bartering in town costs one dollar & a half per day; at harvest-work, one dollar per day & a pint of whiskey.”

After the Revolution, gentlemen seldom sent to England for their gardeners but began to place advertisements for professional gardeners in local newspapers. Just north of Baltimore, Harry Dorsey Gough advertised in 1788, “I want to employ a complete gardener at Perry Hall…to undertake the management of a spacious, elegant Garden & Orchard.” A similar Baltimore notice in 1795, pleaded for a gardener who was specifically adept at managing strictly ornamental flower gardens.

In Richmond, Virginia, Adam Hunter placed a notice in the local paper searching for a “Complete Gardener, with or without a family (the latter would be preferred)” for his land near Fredericksburg in Stafford County.

After the Revolution, white gardeners working in port towns such as Philadelphia, Annapolis, & Baltimore, were as likely to be European as they were to be British. Europeans were favored by some hiring gentry in the postwar years. One gentleman searching for a gardener in Baltimore in the 1790s wrote, “A Dutch or Frenchman speaking English would be preferred.”

In 1782, Robert Monckton Malcolm of Monckton Park, between Neshaminy Ferry and Bristol, on the river, placed an ad in the Pennsylvania Gazette, "Wanted to Hire, Two German young or middle aged single Men, who understand farming, clearing and fencing of land; it will be necessary that one of them understands gardening."

In Prince George's County, Maryland, Rosalie Stier Calvert sought help planning her garden and grounds, and employed Philadelphia artist William Russell Birch in 1805, to draw up a landscape plan for Riversdale. She wrote that he was “busy making plans for the grounds of the house. I think he is very good at it and he is doing them with an eye to economy.”

Her father wasn't so sure she should take Birch's recommendations without a second opinion--his-- and wrote back, “glad to learn that you are using the architect Birch. You must not concern yourself about the cost of the plans. Copy them and send them to me. I’ll give you my observations.”

Occasionally foreign-born gardeners speaking little or no English contracted to work in gardens in the new republic confused their hopeful employers. In October 1816, Rosalie Calvert wrote her sister, “We have a German who seems to be knowledgeable and this greatly relieves me. One small inconvenience, however, is that he doesn’t understand a single word of English.”

By March 1819, the frustrated Rosalie wrote her father, “I recently discharged my German gardener...He knew nothing at all and couldn’t tell a carrot from a turnip.”.

Wednesday, December 12, 2018

Plants in Early American Gardens - Greek Oregano

Greek Oregano (Origanum vulgare subsp. hirtum)

Greek Oregano, native to Greece and Turkey, bears especially flavorful leaves and has a long history of culinary use. Philadelphia nurseryman Bernard McMahon listed Winter Sweet Marjoram (O. heracleoticum), a synonym of Greek Oregano, in The American Gardener’s Calendar (1806). In 1820, George Divers sent Jefferson “Marjoram,” which was another name for Oregano at the time, instead of the “Sweet Marjoram” (Origanum hortensis) requested by Jefferson.

For more information & the possible availability for purchase

Contact The Tho Jefferson Center for Historic Plants or The Shop at Monticello

Contact The Tho Jefferson Center for Historic Plants or The Shop at Monticello

Tuesday, December 11, 2018

Revolutionary War Hero Thaddeus Kosciuszko's Secret 1778 Garden at West Point

When my husband was reading The Peasant Prince by Alex Storozynski, he asked me if I knew of Kosciuszko's 18C garden at West Point. I did not.

c 1810 Artist Kazimierz Wojniakowski (1771-1812) Tadeusz Kosciuszko

Tadeusz Andrzej Bonawentura Kosciuszko (1746 - 1817) arrived in August of 1776, to aid the colonists in their fight against Britain. Born in Lithuania, then a part of Russian Poland, Kosciuszko sailed for America, after an extensive education in military engineering in both Poland & France. On October 18, 1776, Kosciuszko was offered the rank of Colonel of Engineers.

He set about designing a system of fortifications 3 miles downstream from Philadelphia, to protect from any possible attack by the British fleet. Kosciuszko worked on fortifications at Billingsport & Red Bank on the Delaware River until April 1777, at which time he followed his commander General Horatio Gates northward to defend the boundaries of the Canadian Frontier.

Gates asked Kosciuszko to select a site to station the army for what was felt to be a decisive confrontation with the British. Kosciuszko chose Bemis Heights along the Hudson River, fortifying it with five kilometers of earthenworks. From this vantage point the colonists defended themselves in what came to be a turning point in the Revolution, the Battle of Saratoga.

Six months later, George Washington assigned Kosciuszko to the fortification at West Point on the Hudson. West Point was Kosciuszko's greatest engineering achievement. The project took two & a half years to complete with a work force of 82 laborers, 3 masons, and a stone cutter. It would hold 2500 soldiers.

In 1778, West Point served briefly as headquarters for General Washington. For years West Point remained the largest fort in America.

While serving as Fortifications Engineer for West Point, Kosciuszko selected a secluded site for a personal garden on the ledge of a cliff below Fort Arnold. Because it was to be a private place of serenity for reading & contemplation, he never asked soldiers, civilian laborers, or prisoners of war to help him clear away the wild vegetation or to channel the mountain stream, or to cart soil down to the rock-bound garden.

Gardening & portraiture were his favorite pastimes. He devoted much of his spare time at West Point to planning his garden, constructing a fountain & waterfall, & carrying baskets full of soil to the rocky site, so that flowers might have some earth in which to grow. He discovered a spring bubbling from the rocks in the middle of the cliff, and there he fashioned a small fountain.

The garden ruins were discovered in 1802, during the first year of the Military Academy at West Point, and repaired by cadets. The spring water now rises into a marble basin. Seats overlook the fountain & ornamental shrubs dot the site which has a fine prospect of the river from the cliff.

Presidents & military officers as well as ordinary citizens have enjoyed the spot for over 200 years.

1778: Here I had the pleasure of being introduced to Colonel Thaddeus Kosciuszko, a gentleman of distinction from Poland... He had amused himself while stationed at the Point, in laying out a curious Garden in a deep valley, aboudning more in rocks than in soil. I was gratified in viewing his curious water fountain with spraying jets and cascades.--Military Journal during the American Revolutionary War, from 1775-1783; Describing Interesting Events and Transactions of This Period, with Numerous Facts and Anecdotes. Boston: Cottons and Barnard, 1827. Page 138. Entry for July 28, 1778.

1802: Early in this summer of 1802, Lieutenant Macomb and myself repaired to the dilapidated Garden of Kosciuszko, relaid the stone stairway to the dell, and opened the little fountain at the base of Kosciuszko's Rock in the Garden; planted flowers and vines and constructed several seats, which made the spot a pleasant resort for a reading party...--Memoirs of General Gardner Swift. (General Swift was the first graduate of the United States Military Academy.) United States Military Academy Archives, National Archives Record Group 404, Cadet Library, West Point, New York.

1817: The following day, the party at West Point, and Mr. Monroe (President James Monroe), met the officials in the Garden of Kosciuszko, and there he related the following story of that Pole: When Kosciuszko came from Europe wounded, he seemed unable to move when applying to Congress, and received a grant of land. It was said lameness was assumed to excite sympathy among cold-blooded members. Mr. Monroe said it was not, but to impress a Russian spy that he was not longer able to wield a sword, who was so impressed; and Kosciuszko resumed his health lost in a Russian prison. Mr. Monroe said Kosciuszko had been a faithful friend of the American cause, and that he had recently remitted him several hundred dollars to sustain him in his retreat in Switzerland. This sojourn at West Point and the examination of the Cadets, was very refreshing after city fatigues.--Memoirs of General Gardner Swift. Reference: "Tour of President Monroe in the Northern United States, in the Year 1817." United States Military Academy Archives, National Archives Record Group 404, Cadet Library, West Point, New York.

1834: After a fatiguing walk to Fort Putnam, a ruin examined by every visitor to West Point, I sought the retreat called Kosciuszko's Garden. I had seen it in former years, when it was nearly inaccessible to all but clambering youths. It was now a different sort of place. It had been touched by the hand of taste, and afforded a pleasant nook for reading and contemplation. The Garden is about thirty feet in length, and in width, in its utmost extent, not more than twenty feet, and in some parts much less. Near the center of the Garden there is a beautiful basin, near whose bottom, through a small perforation, flows upward a spring of sweet water, which is carried off by overflowing on the east side of the basin toward the River, the surface of which is some eighty feet below the Garden. It was here, when in its rude state, the Polish soldier and patriot sat in deep contemplation on the loves of his youth, and the ills his country had to suffer. It would be a grateful sight to him if he could visit it now, and find that a band of youthful soldiers had, as it were, consecrated the whole military grounds to his fame.--From the Diary of Samuel L. Knapp of New York. United States Military Academy Archives, National Archives Record Group 404, Cadet Library, West Point, New York.

1848: Emerging from the remains of Fort Clinton, the path, traversing the margin of the cliff, passes the ruins of a battery, and descends, at a narrow gorge between huge rocks, to a flight of wooden steps. These terminate at the bottom upon a grassy terrace a few feet wide, over which hangs a shelving cliff covered with shrubbery. This is called Kosciuszko’s Garden, from the circumstance of its having been a favorite resort of that officer while stationed there as engineer for a time during the Revolution. In the center of the terrace is a marble basin, from the bottom of which bubbles up a tiny fountain of pure water. It is said that the remains of a fountain constructed by Kosciuszko was discovered in 1802, when it was removed, and the marble bowl which now receives the jet was placed there. It is a beautiful and romantic spot, shaded by a weeping willow and other trees, and having seats provided for those who wish to linger. Benson J. Lossing. Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution. 1850. Vol. 1. Chapter XXX.

.jpg) Kosciuszko's Garden 19C

Kosciuszko's Garden 19C

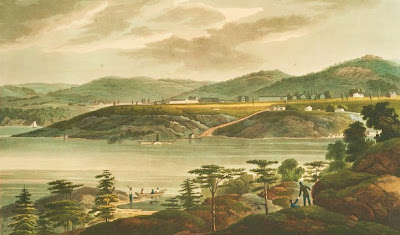

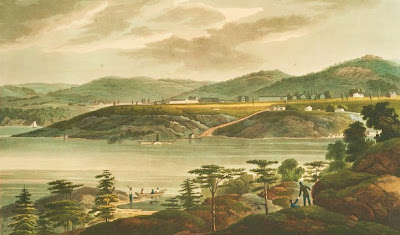

View of West Point on the Hudson River in New York. 19C

View of West Point on the Hudson River in New York. 19C

Kosciuszko's Garden 1963

Kosciuszko's Garden 1963

.jpg) Kosciuszko's Garden 2003

Kosciuszko's Garden 2003

A Little More About Thomas Jefferson and Thaddeus Kosciuszko...

Kosciuszko & Jefferson were dear friends. As abolistionist Kosciuszko was leaving the United States in March, 1798, to avoid the Alien & Sedition Acts, he wrote his will with Jefferson as witness, executor, & beneficiary. Kosciuszko wanted his money to go toward freeing & educating America's slaves, specifically Thomas Jefferson's slaves--all of his slaves, not just Sally Hemings & the her children.

I beg Mr. Jefferson that in the case I should die without will or testament he should bye out of my money So many Negroes and free them, that the restante (remaining) sums should be Sufficient to give them aducation and provide for thier maintenance, that . . . each should know before, the duty of a Cytyzen in the free Government, that he must defend his country against foreign as well as internal Enemies who would wish to change the Constitution for the worst to inslave them by degree afterwards, to have good and human heart Sensible for the Sufferings of others, each must be married and have 100 Ackres of land, wyth instruments, Cattle for tillage and know how to manage and Gouvern it well as well to know [how to] behave to neyboughs [neighbors], always wyth Kindnes and ready to help them . . . . T. Kościuszko.

Jefferson called Kosciuszko "the truest son of liberty I have ever known;" but after the Pole's death, Jefferson did not live up to his pact with his friend, leaving the will to languish in American courts & leaving his slaves to be sold on the lawn of Monticello.

See Gary B. Nash & Graham Russell Gao Hodges. Friends of Liberty: A Tale of Three Patriots, Two Revolutions, and the Betrayal that Divided a Nation: Thomas Jefferson, Thaddeus Kosciuszko, and Agrippa Hull. Basic Books 3, April 2008.

c 1810 Artist Kazimierz Wojniakowski (1771-1812) Tadeusz Kosciuszko

Tadeusz Andrzej Bonawentura Kosciuszko (1746 - 1817) arrived in August of 1776, to aid the colonists in their fight against Britain. Born in Lithuania, then a part of Russian Poland, Kosciuszko sailed for America, after an extensive education in military engineering in both Poland & France. On October 18, 1776, Kosciuszko was offered the rank of Colonel of Engineers.

He set about designing a system of fortifications 3 miles downstream from Philadelphia, to protect from any possible attack by the British fleet. Kosciuszko worked on fortifications at Billingsport & Red Bank on the Delaware River until April 1777, at which time he followed his commander General Horatio Gates northward to defend the boundaries of the Canadian Frontier.

Gates asked Kosciuszko to select a site to station the army for what was felt to be a decisive confrontation with the British. Kosciuszko chose Bemis Heights along the Hudson River, fortifying it with five kilometers of earthenworks. From this vantage point the colonists defended themselves in what came to be a turning point in the Revolution, the Battle of Saratoga.

Six months later, George Washington assigned Kosciuszko to the fortification at West Point on the Hudson. West Point was Kosciuszko's greatest engineering achievement. The project took two & a half years to complete with a work force of 82 laborers, 3 masons, and a stone cutter. It would hold 2500 soldiers.

In 1778, West Point served briefly as headquarters for General Washington. For years West Point remained the largest fort in America.

While serving as Fortifications Engineer for West Point, Kosciuszko selected a secluded site for a personal garden on the ledge of a cliff below Fort Arnold. Because it was to be a private place of serenity for reading & contemplation, he never asked soldiers, civilian laborers, or prisoners of war to help him clear away the wild vegetation or to channel the mountain stream, or to cart soil down to the rock-bound garden.

Gardening & portraiture were his favorite pastimes. He devoted much of his spare time at West Point to planning his garden, constructing a fountain & waterfall, & carrying baskets full of soil to the rocky site, so that flowers might have some earth in which to grow. He discovered a spring bubbling from the rocks in the middle of the cliff, and there he fashioned a small fountain.

The garden ruins were discovered in 1802, during the first year of the Military Academy at West Point, and repaired by cadets. The spring water now rises into a marble basin. Seats overlook the fountain & ornamental shrubs dot the site which has a fine prospect of the river from the cliff.

Presidents & military officers as well as ordinary citizens have enjoyed the spot for over 200 years.

1778: Here I had the pleasure of being introduced to Colonel Thaddeus Kosciuszko, a gentleman of distinction from Poland... He had amused himself while stationed at the Point, in laying out a curious Garden in a deep valley, aboudning more in rocks than in soil. I was gratified in viewing his curious water fountain with spraying jets and cascades.--Military Journal during the American Revolutionary War, from 1775-1783; Describing Interesting Events and Transactions of This Period, with Numerous Facts and Anecdotes. Boston: Cottons and Barnard, 1827. Page 138. Entry for July 28, 1778.

1802: Early in this summer of 1802, Lieutenant Macomb and myself repaired to the dilapidated Garden of Kosciuszko, relaid the stone stairway to the dell, and opened the little fountain at the base of Kosciuszko's Rock in the Garden; planted flowers and vines and constructed several seats, which made the spot a pleasant resort for a reading party...--Memoirs of General Gardner Swift. (General Swift was the first graduate of the United States Military Academy.) United States Military Academy Archives, National Archives Record Group 404, Cadet Library, West Point, New York.

1817: The following day, the party at West Point, and Mr. Monroe (President James Monroe), met the officials in the Garden of Kosciuszko, and there he related the following story of that Pole: When Kosciuszko came from Europe wounded, he seemed unable to move when applying to Congress, and received a grant of land. It was said lameness was assumed to excite sympathy among cold-blooded members. Mr. Monroe said it was not, but to impress a Russian spy that he was not longer able to wield a sword, who was so impressed; and Kosciuszko resumed his health lost in a Russian prison. Mr. Monroe said Kosciuszko had been a faithful friend of the American cause, and that he had recently remitted him several hundred dollars to sustain him in his retreat in Switzerland. This sojourn at West Point and the examination of the Cadets, was very refreshing after city fatigues.--Memoirs of General Gardner Swift. Reference: "Tour of President Monroe in the Northern United States, in the Year 1817." United States Military Academy Archives, National Archives Record Group 404, Cadet Library, West Point, New York.

1834: After a fatiguing walk to Fort Putnam, a ruin examined by every visitor to West Point, I sought the retreat called Kosciuszko's Garden. I had seen it in former years, when it was nearly inaccessible to all but clambering youths. It was now a different sort of place. It had been touched by the hand of taste, and afforded a pleasant nook for reading and contemplation. The Garden is about thirty feet in length, and in width, in its utmost extent, not more than twenty feet, and in some parts much less. Near the center of the Garden there is a beautiful basin, near whose bottom, through a small perforation, flows upward a spring of sweet water, which is carried off by overflowing on the east side of the basin toward the River, the surface of which is some eighty feet below the Garden. It was here, when in its rude state, the Polish soldier and patriot sat in deep contemplation on the loves of his youth, and the ills his country had to suffer. It would be a grateful sight to him if he could visit it now, and find that a band of youthful soldiers had, as it were, consecrated the whole military grounds to his fame.--From the Diary of Samuel L. Knapp of New York. United States Military Academy Archives, National Archives Record Group 404, Cadet Library, West Point, New York.

1848: Emerging from the remains of Fort Clinton, the path, traversing the margin of the cliff, passes the ruins of a battery, and descends, at a narrow gorge between huge rocks, to a flight of wooden steps. These terminate at the bottom upon a grassy terrace a few feet wide, over which hangs a shelving cliff covered with shrubbery. This is called Kosciuszko’s Garden, from the circumstance of its having been a favorite resort of that officer while stationed there as engineer for a time during the Revolution. In the center of the terrace is a marble basin, from the bottom of which bubbles up a tiny fountain of pure water. It is said that the remains of a fountain constructed by Kosciuszko was discovered in 1802, when it was removed, and the marble bowl which now receives the jet was placed there. It is a beautiful and romantic spot, shaded by a weeping willow and other trees, and having seats provided for those who wish to linger. Benson J. Lossing. Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution. 1850. Vol. 1. Chapter XXX.

.jpg) Kosciuszko's Garden 19C

Kosciuszko's Garden 19C View of West Point on the Hudson River in New York. 19C

View of West Point on the Hudson River in New York. 19C Kosciuszko's Garden 1963

Kosciuszko's Garden 1963

.jpg) Kosciuszko's Garden 2003

Kosciuszko's Garden 2003A Little More About Thomas Jefferson and Thaddeus Kosciuszko...

Kosciuszko & Jefferson were dear friends. As abolistionist Kosciuszko was leaving the United States in March, 1798, to avoid the Alien & Sedition Acts, he wrote his will with Jefferson as witness, executor, & beneficiary. Kosciuszko wanted his money to go toward freeing & educating America's slaves, specifically Thomas Jefferson's slaves--all of his slaves, not just Sally Hemings & the her children.

I beg Mr. Jefferson that in the case I should die without will or testament he should bye out of my money So many Negroes and free them, that the restante (remaining) sums should be Sufficient to give them aducation and provide for thier maintenance, that . . . each should know before, the duty of a Cytyzen in the free Government, that he must defend his country against foreign as well as internal Enemies who would wish to change the Constitution for the worst to inslave them by degree afterwards, to have good and human heart Sensible for the Sufferings of others, each must be married and have 100 Ackres of land, wyth instruments, Cattle for tillage and know how to manage and Gouvern it well as well to know [how to] behave to neyboughs [neighbors], always wyth Kindnes and ready to help them . . . . T. Kościuszko.

See Gary B. Nash & Graham Russell Gao Hodges. Friends of Liberty: A Tale of Three Patriots, Two Revolutions, and the Betrayal that Divided a Nation: Thomas Jefferson, Thaddeus Kosciuszko, and Agrippa Hull. Basic Books 3, April 2008.

Monday, December 10, 2018

Flowers in Early American Gardens - Corn Poppy

Poppies are shown in full bloom in a field near Sommepy-Tahure, France.

Thomas Jefferson planted "Papaver Rhoeas flor. plen. double poppy" at Monticello in 1807. This is a horticultural variety of the common European field poppy, which was immortalized in Flanders during World War I. The Corn Poppy is a hardy, self-seeding annual that bears single, red flowers in early summer. Jefferson noted corn poppies growing in 1767 at Shadwell, and he planted a double-flowering form of the flower in a Monticello oval flower bed in 1807.

Corn poppies bloomed in the between trench lines during WWI and have come to symbolize the bloodshed of soldiers who perished in those horrific battles.

How poppies, strong and fragile, became a symbol of WWI devastation

"The corn poppy is a pesky weed, a sweet, delicate garden flower and, for the past century, the emblem of the human cost of war.

"The custom of wearing paper poppies to remember that cost has waned in the United States but remains strong in Britain, the scene of national ceremonies Sunday to mark the armistice that ended World War I in 1918. (World leaders also gathered in Paris.) More than 40 million paper poppies are distributed by the Royal British Legion each year, and all the country’s leaders, including Queen Elizabeth, wear them.

"Between 1914 and 1918, the armies of Europe faced off for war in the machine age. Along the Western Front, the fixed nature of entrenched warfare led to mass destruction on every level. At their most intense, artillery batteries could lay down 10 shells per second...The shelling unearthed untold millions of dormant, buried poppy seeds, which began to germinate, grow and bloom.

"After one of his comrades was killed, the Canadian field surgeon John McCrae penned the enduring poem linking the corn poppy to the slaughter of industrialized warfare. “In Flanders fields the poppies blow/Between the crosses, row on row...”

"The paradox of the corn poppy is that it is a wildflower — farmers view it as a weed — that is individually delicate and fleeting but capable of appearance in vast colonies. It is both strong and fragile, like all life.

"Gardeners love poppies for their ability to bring pure, natural beauty to a cultivated setting. It is a plant that goes through a months-long dance. First, the seedlings develop into a ground-hugging rosette of gray-green leaves. When the weather warms up, the rosette rises up and expands, and from its center emerges a wire-like stem dressed in silver hairs. At the top, a little elongated bud nods in its gooseneck until the bud coverings are cast off and the blossom arches up to the sun. The petals are thin and crinkled, like silk, and soon fall away to reveal a button-like seedpod that a month or so later will contain hundreds of tiny ripe seeds, each smaller than a pinhead..."

For more information & the possible availability for purchase

Contact The Tho Jefferson Center for Historic Plants or The Shop at Monticello

Thomas Jefferson planted "Papaver Rhoeas flor. plen. double poppy" at Monticello in 1807. This is a horticultural variety of the common European field poppy, which was immortalized in Flanders during World War I. The Corn Poppy is a hardy, self-seeding annual that bears single, red flowers in early summer. Jefferson noted corn poppies growing in 1767 at Shadwell, and he planted a double-flowering form of the flower in a Monticello oval flower bed in 1807.

Corn poppies bloomed in the between trench lines during WWI and have come to symbolize the bloodshed of soldiers who perished in those horrific battles.

How poppies, strong and fragile, became a symbol of WWI devastation

"The corn poppy is a pesky weed, a sweet, delicate garden flower and, for the past century, the emblem of the human cost of war.

"The custom of wearing paper poppies to remember that cost has waned in the United States but remains strong in Britain, the scene of national ceremonies Sunday to mark the armistice that ended World War I in 1918. (World leaders also gathered in Paris.) More than 40 million paper poppies are distributed by the Royal British Legion each year, and all the country’s leaders, including Queen Elizabeth, wear them.

"Between 1914 and 1918, the armies of Europe faced off for war in the machine age. Along the Western Front, the fixed nature of entrenched warfare led to mass destruction on every level. At their most intense, artillery batteries could lay down 10 shells per second...The shelling unearthed untold millions of dormant, buried poppy seeds, which began to germinate, grow and bloom.

"After one of his comrades was killed, the Canadian field surgeon John McCrae penned the enduring poem linking the corn poppy to the slaughter of industrialized warfare. “In Flanders fields the poppies blow/Between the crosses, row on row...”

"The paradox of the corn poppy is that it is a wildflower — farmers view it as a weed — that is individually delicate and fleeting but capable of appearance in vast colonies. It is both strong and fragile, like all life.

"Gardeners love poppies for their ability to bring pure, natural beauty to a cultivated setting. It is a plant that goes through a months-long dance. First, the seedlings develop into a ground-hugging rosette of gray-green leaves. When the weather warms up, the rosette rises up and expands, and from its center emerges a wire-like stem dressed in silver hairs. At the top, a little elongated bud nods in its gooseneck until the bud coverings are cast off and the blossom arches up to the sun. The petals are thin and crinkled, like silk, and soon fall away to reveal a button-like seedpod that a month or so later will contain hundreds of tiny ripe seeds, each smaller than a pinhead..."

For more information & the possible availability for purchase

Contact The Tho Jefferson Center for Historic Plants or The Shop at Monticello

Sunday, December 9, 2018

Plants - On Virginia's wild stoned fruits - Robert Beverley History of Virginia 1705

The History and Present State of Virginia, in Four Parts published originally in London in 1705. Beverley, Robert, ca. 1673-1722.

OF THE WILD FRUITS OF THE COUNTRY.

§11. Of fruits, natural to the country, there is great abundance, but the several species of them are produced according to the difference of the soil, and the various situation of the country; it being impossible that one piece of ground should produce so many different kinds intermixed. Of the better sorts of the wild fruits that I have met with, I will barely give you the names, not designing a natural history. And when I have done that, possibly I may not mention one-half of what the country affords, because I never went out of my way to enquire after anything of this nature.

§12. Of stoned fruits, I have met with three good sorts, viz: Cherries, plums and persimmons.

1. Of cherries natural to the country, and growing wild in the woods, I have seen three sorts. Two of these grow upon trees as big as the common English white oak, whereof one grows in bunches like grapes. Both these sorts are black without, and but one of them red within. That which is red within, is more palatable than the English black cherry, as being without its bitterness. The other, which hangs on the branch like grapes, is water colored within, of a faintish sweet, and greedily devoured by the small birds. /The third sort is called the Indian cherry, and grows higher up in the country than the others do. It is commonly found by the sides of rivers and branches on small slender trees, scarce able to support themselves, about the bigness of the peach trees in England. This is certainly the most delicious cherry in the world; it is of a dark purple when ripe, and grows upon a single stalk like the English cherry, but is very small, though, I suppose, it may be made larger by cultivation, if anybody would mind it. These, too, are so greedily devoured by the small birds, that they won't let them remain on the tree long enough to ripen; by which means, they are rarely known to any, and much more rarely tasted, though, perhaps, at the same time they grow just by the houses.

2. The plums, which I have observed to grow wild there, are of two sorts, the black and the Murrey plum, both which are small, and have much the same relish with the damson.

3. The persimmon is by Heriot called the Indian plum; and so Smith, Purchase, and Du Lake, call it after him; but I can't perceive that any of those authors had ever heard of the sorts I have just now mentioned, they growing high up in the country. These persimmons, amongst them, retain their Indian name. They are of several sizes, between the bigness of a damson plum and a burgamot pear. The taste of them is so very rough, it is not to be endured till they are fully ripe, and then they are a pleasant fruit. Of these, some vertuosi make an agreeable kind of beer, to which purpose they dry them in cakes, and lay them up for use. These, like most other fruits there, grow as thick upon the trees as ropes of onions: the branches very often break down by the mighty weight of the fruit.

OF THE WILD FRUITS OF THE COUNTRY.

§11. Of fruits, natural to the country, there is great abundance, but the several species of them are produced according to the difference of the soil, and the various situation of the country; it being impossible that one piece of ground should produce so many different kinds intermixed. Of the better sorts of the wild fruits that I have met with, I will barely give you the names, not designing a natural history. And when I have done that, possibly I may not mention one-half of what the country affords, because I never went out of my way to enquire after anything of this nature.

§12. Of stoned fruits, I have met with three good sorts, viz: Cherries, plums and persimmons.

1. Of cherries natural to the country, and growing wild in the woods, I have seen three sorts. Two of these grow upon trees as big as the common English white oak, whereof one grows in bunches like grapes. Both these sorts are black without, and but one of them red within. That which is red within, is more palatable than the English black cherry, as being without its bitterness. The other, which hangs on the branch like grapes, is water colored within, of a faintish sweet, and greedily devoured by the small birds. /The third sort is called the Indian cherry, and grows higher up in the country than the others do. It is commonly found by the sides of rivers and branches on small slender trees, scarce able to support themselves, about the bigness of the peach trees in England. This is certainly the most delicious cherry in the world; it is of a dark purple when ripe, and grows upon a single stalk like the English cherry, but is very small, though, I suppose, it may be made larger by cultivation, if anybody would mind it. These, too, are so greedily devoured by the small birds, that they won't let them remain on the tree long enough to ripen; by which means, they are rarely known to any, and much more rarely tasted, though, perhaps, at the same time they grow just by the houses.

2. The plums, which I have observed to grow wild there, are of two sorts, the black and the Murrey plum, both which are small, and have much the same relish with the damson.

3. The persimmon is by Heriot called the Indian plum; and so Smith, Purchase, and Du Lake, call it after him; but I can't perceive that any of those authors had ever heard of the sorts I have just now mentioned, they growing high up in the country. These persimmons, amongst them, retain their Indian name. They are of several sizes, between the bigness of a damson plum and a burgamot pear. The taste of them is so very rough, it is not to be endured till they are fully ripe, and then they are a pleasant fruit. Of these, some vertuosi make an agreeable kind of beer, to which purpose they dry them in cakes, and lay them up for use. These, like most other fruits there, grow as thick upon the trees as ropes of onions: the branches very often break down by the mighty weight of the fruit.

Saturday, December 8, 2018

Plants in Early American Gardens - Red Fig Tomato

Red Fig Tomato is an heirloom variety from Philadelphia dating to 1805. They were traditionally dried or made into a sweet preserve to be eaten in winter like figs, but they are also sugary sweet eaten fresh. The deep red fruits are pear-shaped and about 1½ inches long.

For more information & the possible availability for purchase

Contact The Tho Jefferson Center for Historic Plants or The Shop at Monticello

Contact The Tho Jefferson Center for Historic Plants or The Shop at Monticello

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

+Tadeusz+Kosciuszko.jpg)