In landscape terminology, an alcove usually refers to a recess in a garden or pleasure ground, originally in the wall surrounding the garden; but in the late 18th-century, when protective brick & stone walls were used less, the term often referred to any covered retreat standing in a garden like a bower or summerhouse.

Alcoves provided protection from the sun in summer months, and shelter from winds while allowing the sun to shine through in colder weather. Placement of an alcove gave visual & structural definition to the garden. Their situation was often used to give a pleasing view of the garden or the surrounding landscape. And, an alcove provided a private resting place for reading or courting.

Sometimes hedges would be shaped into alcoves to frame statues or garden seats or tables for outdoor dining or small flower beds. The shapes of alcoves occasionally would echo architectural features of the house or nearby structures. Alcoves could accentuate a plant, or a statue, or a garden pond, as well as provide shelter for the garden owners & their guests.

In early America there are many references to vine & leaf-covered alcoves, but most of those are in England or in the minds of poets and fiction writers. Early in the 18th-century, English garden alcoves are referred to in Joseph Addison's Rosamond an Opera in 1707. There are several visual references to garden alcoves in stone walls in colonial & early American paintings. The 1766 William Williams (American Colonial Era artist, 1727-1791) painting of Deborah Richmond which is in the Brooklyn Museum of Art, depicts Deborah in front of a curved stone wall with statues in alcoves.

1766 William Williams (1727–1791) Deborah Richmond

The Henry Benbridge (American Colonial Era painter, 1743-1812) painting of 1779 representing the Enoch Edwards Family at the Philadelphia Museum of Art depicts the family gathered around a garden alcove. It is not clear whether these paintings are actual representations of American colonial surroundings or whether the backgrounds were adapted from earlier English paintings or prints.

1779 Henry Benbridge 1743-1812 Enoch Edwards Family

The first written reference I can find to alcoves actually existing in American gardens appears in the summer of 1772, The South Carolina Gazette and Country Journal reported, "In a Garden belonging to Mr. TYERS... is a Walk terminated by a beautiful Alcove...In which are two elegantly carved Pedestals, on which are placed a Gentleman and Lady's Scull."

"The same newspaper carried an ode to spring in 1774, "The verdant foliage of the shady grove Attracts the enraptur'd mind with new delight; The thousand beauties of yon sweet alcove, Where gentle zephyrs wing their airy flight."

Robert Adam Croome Landscape Park, Worcestershire, UK

Robert Adam Croome Landscape Park, Worcestershire, UKIn 1789, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe described waking in an alcove in The Sorrows of Werter: a German Story. "The dense vapours of the early morn conceal yon verdant valley from my sight; and now the rising fun exhales the glittering dew, and plays upon the thick foliage that o'er-canopies my head; while here and there some feeble rays pierce through my favourite alcove, chequering the gloomy shade with glimmering light."

Alcove in Plantation Garden Pond, Norfolk, UK

Alcove in Plantation Garden Pond, Norfolk, UKIn 1794, when visitor Henry Wansey noted that at Gray's Gardens, a public pleasure garden in Philadelphia, in 1794, "The ground has every advantage of hill and dale, for being laid out in great variety; and it is neatly decorated with arbours, shady walks, etc."

Rosa 'Paul's Himalayan Musk' growing over hedge with wooden bench seat in yew alcove. Jonathan Buckley

In 1801, in Wilmington, North Carolina, Eliza Clitherall recorded that "The Gardens were large...There was alcoves and summer houses at the termination of each walk, seats under trees in the more shady recesses of the Big Garden."

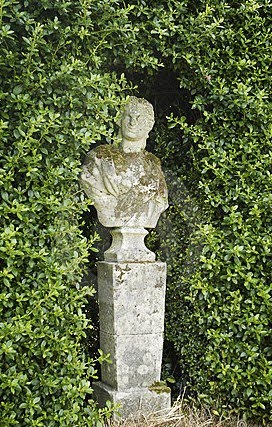

Statue in a clipped hedge alcove

Statue in a clipped hedge alcoveIn James Anderson's 1801 Recreations in Agriculture, Natural-history, Arts, and Miscellaneous Literature he describes his alcove "I have in my garden a summer-seat that fronts the east, with an opening nine feet in width. It is covered above with a sloping roof, which slants towards the opening, so that the light comes full upon the lower part of it, though it rises in the front part between two and three feet above the top of the opening. The whole is covered with a (grape) vine; and, thinking that the vine-leaves would make a lively and rural appearance if spread along the roof, I introduced some shoots into it for that purpose. These grew very well, and made tolerably vigorous shoots, especially towards the lower part, where it is most exposed to the light. But although there were some bunches of grapes upon the shoots of the first year, yet they all proved abortive, a very few berries only having set, and these soon fell off. The vine has been cut and trained in this kind of alcove for three years, but has never since showed the smallest rudiment of fruit on any part."

Chillington Hall in Stafforshire, UK

Chillington Hall in Stafforshire, UKEnglish writer John Claudius Loudon tells a melancholy tale of an alcove in his 1806 Treatise on Forming, Improving, and Managing Country Residences, "Soon after this, he quietly expires on a seat in the Saxon alcove at the end of the western terrace, where in an evening of September he had sat down with his family to admire the splendour of the sky, the gloom of the distant mountains, the reflection of the evening sun, and the lengthened shadow of the islands upon the still expanse of the lake."

The Pebble Alcove at Stowe Garden, UK.

Fiction writers use the secretive, vine-covered alcove for mystery and romance. Englishman John Perry writes in The New London Gleaner in 1809, "We entered a small garden ; a little paradise of neatness and taste.—" Hush !" cried the father, approaching a verdant alcove, canopied with the trembling foliage of the vine, enwreathed with woodbine."

Statue in a stone alcove

Statue in a stone alcoveThe Literay Gazette in London carried a story by John Mounteney Jephson in 1820, "With a palpitating heart, he went to the gate which led to the garden where the musical party were sitting, in an alcove covered with vines...when he entered the alcove, it was so obscured by the umbrageous leaves of vines, with which it was covered, that the faces of the company could not be easily distinguished."

Alcoves on Old London Bridge. Joseph Mallord William Turner

Old London Bridge Alcoves in Victoria Park moved 1860

Alcoves on Old London Bridge

One of the Old London Bridge Alcoves in Victoria Park in the courtyard of Guy's Hospital - right next to the Thames (opposite the Houses of Parliament) moved in 1860

Old London Bridge Alcoves in Victoria Park moved in 1860

Stone urn on plinth in alcove in Fagus - Beech hedge. Silverstone Farm, Norfolk, UK. Marcus Harpur

The Gothic Alcove at Painswick Rococo Garden, Painswick, Gloucestershire, UK. Charles Hawes

The Gothic Alcove situated at the end of a Beech walk. Painswick Rococo Garden, Painswick, Gloucestershire , UK. Carole Drake

Alcove in stone wall. Mappercombe Manor garden, Dorset, UK. Charles Hawes

Pink rose in pot placed in alcove in Italian town garden. Mirella Collavini Prescot

Painted arbour with seat in hedge alcove at Hazlebury Manor, Wiltshire, UK. Jerry Harpur

Alcove

Bowl of fruit statue in alcove at Plas Brondanw, Wales, UK. Charles Hawes

Boxwood topiary in terracotta container against reclaimed brick wall from Russell Watkinson Landscapes, Tatton Flower Show 2008

Buddadvasu Flickr

Container with contrasting colored plant placed in alcove cut into beech hedge at Selehurst in Sussex, UK. John Glover

Alcove by Linen and Lavender.

.

.jpg) Hampton Mansion, Entrance Facade, Towson, Maryland.

Hampton Mansion, Entrance Facade, Towson, Maryland. Hampton Mansion, Garden Facade, Towson, Maryland.

Hampton Mansion, Garden Facade, Towson, Maryland. Recently installed parterres at Hampton Mansion, Towson, Maryland.

Recently installed parterres at Hampton Mansion, Towson, Maryland.

.+Rebecca+Orne+(later+Mrs.+Joseph+Cabot).+Worcester+Museum+of++Art..jpg)

+pvt1st-gallery-art.com.jpg)

.+Girl+with+a+Squirrel..jpg)

Mount Clare Entrance Gates, Baltimore, Maryland.

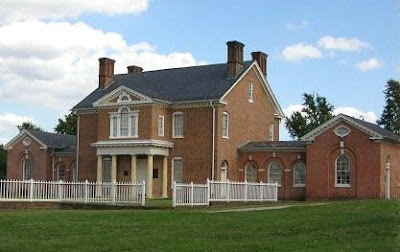

Mount Clare Entrance Gates, Baltimore, Maryland. Mount Clare Entrance Facade, Baltimore, Maryland.

Mount Clare Entrance Facade, Baltimore, Maryland. Mount Clare Garden Facade, Baltimore, Maryland.

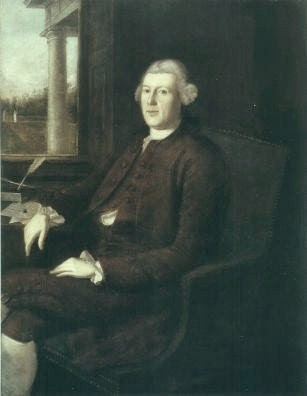

Mount Clare Garden Facade, Baltimore, Maryland. Charles Carroll the Barrister (1723-83) at the Entrance Facade by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827)

Charles Carroll the Barrister (1723-83) at the Entrance Facade by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) Margaret Tilghman Carroll (1743-1817) at the Garden Facade by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827)

Margaret Tilghman Carroll (1743-1817) at the Garden Facade by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) View of Mount Clare from the Lower Garden area by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827)

View of Mount Clare from the Lower Garden area by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) Young men who had apprenticed to other trades were sometimes called into garden service during the growing season. In Annapolis, craftsman William Faris used his clockmaking apprentice as garden help on several occasions.

Young men who had apprenticed to other trades were sometimes called into garden service during the growing season. In Annapolis, craftsman William Faris used his clockmaking apprentice as garden help on several occasions. A lad named Cornelius Lary was bound out by his older sister at the age of 10, as a gardening apprentice to John Toon, who operated Toon’s Garden in Baltimore County. Toon’s Garden was one of several commercial pleasure gardens operating in the Baltimore area at the turn of the century. In the 1800-1801 Baltimore City directory, the 10-acre Toon’s Gardens was described as being “situated about two miles down the [Patapsco] river…on an elevated situation,” & was said to “command a view of the city & bay...During the summer months,” the directory recounted, “a great concourse of citizens make excursions by land & water to these Gardens…with all kinds of refreshments.”

A lad named Cornelius Lary was bound out by his older sister at the age of 10, as a gardening apprentice to John Toon, who operated Toon’s Garden in Baltimore County. Toon’s Garden was one of several commercial pleasure gardens operating in the Baltimore area at the turn of the century. In the 1800-1801 Baltimore City directory, the 10-acre Toon’s Gardens was described as being “situated about two miles down the [Patapsco] river…on an elevated situation,” & was said to “command a view of the city & bay...During the summer months,” the directory recounted, “a great concourse of citizens make excursions by land & water to these Gardens…with all kinds of refreshments.” After the Revolution, growing numbers of immigrant European, Caribbean, & British independent gardeners, assisted by white apprentices & free & slave blacks, took over the work. The American Revolution was the turning point in the development of independent gardening in the newly emerging capitalist nation, However, some aspects of Mid-Atlantic & South gardening did not change until the Civil War.

After the Revolution, growing numbers of immigrant European, Caribbean, & British independent gardeners, assisted by white apprentices & free & slave blacks, took over the work. The American Revolution was the turning point in the development of independent gardening in the newly emerging capitalist nation, However, some aspects of Mid-Atlantic & South gardening did not change until the Civil War.

++Mount+Vernon++London+Lib+Cong.jpg)

++Mount+Vernon.jpg)

+Mount+Vernon+(2).jpg)

+The+Old+Mount+Vernon+1857.jpg)

+Kitchen+at+Mount+Vernon.jpg)