These houses & grounds built on eminences & commanding grand views & prospects do seem to create an impression of a powerful owner.

The Plantation. Probably an idealized view of a Virginia plantation. 1825. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

The Plantation. Probably an idealized view of a Virginia plantation. 1825. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.The house Druid Hill still exists within the 745 acre Druid Hill Park in Baltimore, Maryland, which ranks with New York's Central Park begun in 1859, and Fairmount Park in Philadelphia, as one of the oldest landscaped public parks in the United States.

The land was originally part of Auchentorlie, the estate of George Buchanan, one of the 7 original commissioners of Baltimore City. The dwelling was rebuilt after a fire & renamed Druid Hill in 1797 by Colonel Nicholas Rogers, a flour merchant & amateur architect, who married Eleanor Buchanan who had inherited the property.

The estate of Druid Hill was purchased for use as a park in 1860, by the city of Baltimore with the revenue derived from a one-cent park tax on the nickel horsecar fares. The house is now used as the administrative headquarters for the Baltimore Zoo which is located in the park.

Francis Guy. 1811 View of Seat of Col. Roger near Baltimore, depicts Druid Hill in Baltimore, Maryland, now the administrative headquarters for the Baltimore Zoo.

Francis Guy. 1811 View of Seat of Col. Roger near Baltimore, depicts Druid Hill in Baltimore, Maryland, now the administrative headquarters for the Baltimore Zoo.Many of the existing depictions of these houses high upon the hills of the new nation come from English artist Francis Guy and from English engraver & designer William R. Birch.

London silk dyer Francis Guy (1760-1820) arrived in Baltimore in 1795, where he worked at that trade until 1799. From 1800 to 1815, he was known as a landscape painter, holding his 1st exhibit in 1803.

Guy painted country estates on canvas & furniture plus scenes from the War of 1812. Guy was also an inventor & writer of religious essays & poetry. He moved to Brooklyn, New York, about 1817, painting in that state until his death.

William Russell Birch (1755-1834) View of Montebello, the Seat of General Samuel Smith. The plan for Montebello still exists at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

William Russell Birch (1755-1834) View of Montebello, the Seat of General Samuel Smith. The plan for Montebello still exists at the Baltimore Museum of Art.Montebello was designed by Birch and was probably begun in 1799. Birch may have met General Smith, when Smith was in Philadelphia serving as a U. S. Representative.

Montebello in Baltimore, Maryland, about 1899. Photograph at the Maryland Historical Society.

Montebello in Baltimore, Maryland, about 1899. Photograph at the Maryland Historical Society.Englishman Birch immigrated to Philadelphia in 1794, hoping to make his living producing books of scenes of the new nation in order to promote "taste" in architecture & landscape design. His The City of Philadelphia in 1800 went through 4 editions to 1828.

Birch's 3rd publication, The Country Seats of the United States published in 1808, resulted from Birch's travels along the Atlantic coast & contained 20 views including one of New Orleans.

Francis Guy. Perry Hall near Baltimore, about 1803.

Francis Guy. Perry Hall near Baltimore, about 1803.In 1774, wealthy merchant & planter Harry Dorsey Gough (1745-1808) purchased an 1,000 acre estate called the Adventure north of Baltimore. Gough renamed the estate after his family's home, Perry Hall in Perry Barr, Birmingham, England. From the 16-room mansion on the hill, Gough administered his plantation's operation, where dozens of slaves tended cattle, various food crops, and stands of tobacco.

Visitors commented on the distinctive architectural features of the home on the hill as well as the lush gardens on the surrounding grounds. The impressive wine cellars & expansive grand hall used for entertaining symbolized Gough's socially prominent, powerful life before his profound religious conversion. Gough then built a chapel near the mansion's eastern wing that allowed him to quietly pursue his worship, along with his family, servants, & neighboring landowners.

It was at Perry Hall mansion that plans for the American Methodist Episcopal Church were developed by Gough, his Birmingham neighbour Francis Asbury, & other religious leaders. In 1808, Asbury would write that "Mr. Gough had inherited a large estate from a relation in England, and having the means, he indulged his taste for gardening and the expensive embellishment of his country seat, Perry Hall, which was always open to visitors, especially those who feared God."

Parnassas Hill home of Dr. Henry Stevenson by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) about 1769. Maryland Historical Society.

Parnassas Hill home of Dr. Henry Stevenson by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) about 1769. Maryland Historical Society.An earlier Maryland neighbor, who also built high up on a hill, had helped found the Presbyterian Church in Baltimore in 1763. Irishman Dr. Henry Stevenson (1721-1814) built Parnassus Hill between 1763 & 1769 on the Jones Falls north of Baltimore, where he & his brother, also a physician, actually made their money as wheat exporters. Dr. Henry Stephenson, who had come to Maryland in 1745, also pursued medicine pioneering a smallpox vaccine.

In February of 1769, the Maryland Gazette noted, "Dr. Henry Stevenson devotes part of his mansion on 'Parnassus Hill' to the use of an Inoculating Hospital, and opens it to all who may apply." The hospital closed in 1777, as staunch loyalist Stevenson left Baltimore to serve in the British service as a surgeon in New York, returning to Baltimore in 1786, when Revolutionary tempers had cooled. The terraced gardens at the combination home & hospital were among the earliest in Baltimore.

Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) painting of William Paca with the naturalized area of his garden in the background.

Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) painting of William Paca with the naturalized area of his garden in the background.William Paca (1740-1799), a signer of the Declaration of Independnce & a federal district court judge, was born in Harford County, Maryland, and educated in Philadelphia and London. In 1763, Paca ensured his social & economic position by marrying Mary Chew, the daughter of a wealthy Maryland family.

William Paca's falling, terraced garden in Annapolis.

William Paca's falling, terraced garden in Annapolis.Four days after their wedding, Paca purchased two lots in Annapolis and began building the five-part mansion plus an extensive pleasure garden.

View from William Paca's house across his garden to the city of Annapolis.

View from William Paca's house across his garden to the city of Annapolis.Constructed between 1763-1765, the estate is known chiefly for its elegant falling gardens including 5 terraces, a fish-shaped pond, and a wilderness garden.

View from the natural area of William Paca's garden up to the house.

View from the natural area of William Paca's garden up to the house.One of my favorite early depictions of the view from a garden out into the surrounding countryside is at Colonial Williamsburg. It is fun not only for its view, but also for the dog, its master, and the busts of busts.

William Dering painted this portrait of young George Booth between 1748-1750 in Virginia, showing the view of the countryside beyond the garden.

William Dering painted this portrait of young George Booth between 1748-1750 in Virginia, showing the view of the countryside beyond the garden.A much later view of the surrounding countryside just outside of the doorway of a home built on the highest prospect is below.

1835 painting by Ambrose Andrews of the Children of Nathan Starr in Middletown, Connecticut, with a beautiful view of the countryside just outside the doorway.

1835 painting by Ambrose Andrews of the Children of Nathan Starr in Middletown, Connecticut, with a beautiful view of the countryside just outside the doorway.Falling terraced gardens and houses built on the highest property continued as a tradition, as settlers moved from the Atlantic coast down the Ohio River.

+Tadeusz+Kosciuszko.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

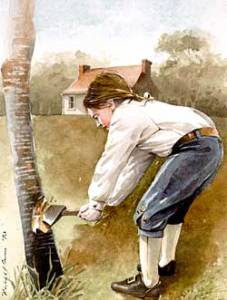

The moment anyone mentions trees and George Washington, you probably think of the famous Cherry Tree Story. However, this tale of young George taking a hatchet to his father cherry tree and, when confronted about the act, asserting "I cannot tell a lie" is probably just that -- a story meant to demonstrate the integrity of the Father of Our Country. In reality, the trees of Ferry Farm have a much more fascinating history. Their story reflects, on a small local scale, vast environmental changes in eastern North America and shifting American attitudes toward the environment throughout the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries.

The moment anyone mentions trees and George Washington, you probably think of the famous Cherry Tree Story. However, this tale of young George taking a hatchet to his father cherry tree and, when confronted about the act, asserting "I cannot tell a lie" is probably just that -- a story meant to demonstrate the integrity of the Father of Our Country. In reality, the trees of Ferry Farm have a much more fascinating history. Their story reflects, on a small local scale, vast environmental changes in eastern North America and shifting American attitudes toward the environment throughout the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries.

+Benjamin+Franklin+(1706-1790)+in+France.jpg)

+Versailles.jpg)